Seeing Things

TOBI TOBIAS on dance et al...

Friday, May 20, 2005

THE BOURNONVILLE FESTIVAL, LOOKING BACK

2005 is the 200th birthday of August Bournonville, the dancer, choreographer and ballet master who gave the Royal Danish Ballet its distinctive profile. To mark the occasion, the company has organized the 3rd Bournonville Festival, which will take place in Copenhagen, June 3-11. All of the Bournonville ballets that are still danced today will be performed on the stage of the Royal Theatre, along with the codified classes devised to preserve the choreographers unique style. A host of museum exhibitions will complement these events. The first Bournonville Festival took place in 1979, the 100th anniversary of Bournonvilles death, and the occasion has become legendary. I wrote an account of it for Dance magazine (March 1980) that I offer here as background for the reports Ill be making on the coming Festival.

THE FESTIVAL IN COPENHAGEN

Its almost impossible to dismiss affection in talking about the Royal Danish Ballets dancing Bournonville. Perhaps one shouldnt. Its almost impossible to dismiss affection in talking about the Royal Danish Ballets dancing Bournonville. Perhaps one shouldnt.

To mark the centenary of the choreographers death, the company staged a week of performances, November 24-30, 1979, of the Bournonville ballets that have survived into the present: La Sylphide (1836), Napoli (1842), Konservatoriet (1849), Kermesse in Bruges (1851), A Folk Tale (1854), La Ventana (1854; 1856), the pas de deux from The Flower Festival in Genzano (1858), Far from Denmark (1860), and The Kings Volunteers on Amager (1871). Although August Bournonville is among the three or four pivotal choreographer-ballet masters of the nineteenth century, and indisputably the most significant figure in the history of Danish dance, the majority of these works are rarely seen complete outside their native environment. The mounting delight of the audience in the course of the weeks showingsculminating in jubilant ovations unprecedented in this sedate theaterestablished a bond among the spectators and between the spectators and artists that promised to be cherished and enduring.

The audience was an international one: dance fans, scholars, and criticsAmericans especiallyconverged on Copenhagen for the Festival. Nightly performances were given in the jewel-box Royal Theatre (built in the last years of Bournonvilles career), which allows an intimacy lost in our formidable opera houses. In addition, there was a profusion of complementary exhibitions and events. Among them, the Bournonville collection assembled at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts was a miracle of particularizing and revivifying the pastthrough its displays of costumes and stage designs, convoluted manuscripts and diagrams that notated the ballets choreography and production details, the brown-inked diaries that became My Theatre Life (the choreographers autobiography, recently published by Wesleyan University Press in Patricia McAndrews long-awaited English translation), the raised chair from which Bournonville oversaw classes, his ballet-master stick, and old postcard-photos of several decades of performers. Depicted among these charming souvenirs were Juliette, Sophie, and Amalie Price, for whom Bournonville made the affectionate Pas des Trois Cousines, and their descendant, Ellen Price, the model for the statue of Hans Christian Andersens Little Mermaid, who gazes out wistfully over Copenhagens harbor.

Some forty ranking professionals (one wishes the protocol had been somewhat more relaxed) were also treated to events such as a lecture-demonstration by Kirsten Ralov (the companys assistant director) on the raked stage of the old Court Theatre, where Bournonville danced as a boy, and to a fascinating inch-by-inch tour of the present theater. This visit disclosed an intricate backstage world with inventive, old-fashioned mechanics for stage magicthe device that flies the Sylph heavenward, for example, complete with its two child-sized safety harnesses for her attendant sylphlings.

There were videotape and film screenings of Bournonville-related material, ranging from the Peter Elfelt fragments showing Royal Danish Ballet dancers at the turn of the century, through homemade footage of the lost Romeo and Juliet Frederick Ashton choreographed on the company in 1955, to contemporary television productions tackling the subject of Bournonville now. (This is a thorny problem for the Danish dance world, which tends to be ambivalent about its national treasure.) Aside from lively intermission conversations, there were impromptu convocations (fueled by supplies from the all-night sműrrebrűd shop) to marvel at and argue about what was being seen and formal receptions glowing in their traditional Danish candlelit welcome. One felt embraced by the occasion.

And then there was the city itself. Copenhagen is a walkers town. One comes to believe, without much exaggeration, that one can encompass the entire city on foot, strolling from the Town Hall Square with its landmark clock-in-the-tower, to the Royal Theatre at Kongens Nytorv, to the antique-and-rare-book haunts of the University Quarter; from canal to harbor to the park-with-a-windmill built on the spiraling city ramparts. The major streets are graciously wide, with long stretches closed to traffic; these are lined with shops, many of which specialize in gleaming china and glass dining ware. The main thoroughfares branch off into crooked byways that invite you to discover, serendipitously, the charm of an old housea tiny, turquoise-tinted row house, perhaps, where Hans Christian Andersen (a would-be ballet dancer once, and Bournonvilles friend) lived for a decade, or tranquil Old World courtyards overlooked by the windows of fastidiously cared-for homes.

The predominant style of architecture is a Dutch Baroque, which gives any building short of a palace a cottagey look. The palaces themselvesthe Amalienborg, where tin-soldier sentries pace up and down, guarding their queen, and Christianborg Castle, which might be the setting for a medieval fableare human in scale, as is everything in the city. The Round Tower, designed for astronomical observation, is a mere 115 feet high. The bourgeois temperament prevails everywhere: While Copenhagen is undeniably one of the worlds pornography capitals, the pharmaceutical matter-of-factness with which sexually titillating devices are displayed is more amusing than arousing, while subtler examples of eroticism are rather like the sculpture chosen by the Glyptotek Museum for its house posterGerhard Hennings Reclining Nude, ingenuous in her sensuality.

The complement of this snug, delectable comfort and human proportion is the sudden incidence of chimerical architecturethe Stock Exchange, built for sober, pragmatic transactions, is crowned with the twined tails of four copper dragonsand of sites like illusions: rising out of nowhere theres a cobblestone hill, studded with slender, gnarled trees growing out of little clearings.

The November weather was characteristic of early winter in Scandinavia: wet, often stingingly cold, the daytime sky taking on the silvery gray-green tinge of the nearby sea. By four each afternoon, the long, luminous twilight had set in and a sliver of moon hovered over the dark, grooved roofs of the city. Intriguing as it was to walk by the hour in this strangely silent fantasy land, it was then all the more pleasant to come inside and envelop oneself in the peculiarly Danish hearth-culture, where heat, light, the hospitality of the table, and easy, open friendliness provide not just homely luxury but a sense of immutable security.

It seems to me that Copenhagens ambience is embodied in Bournonvilles ballets: the human scale; the lavishing of attention on details of quotidian life; the idea of homeof domesticityas a haven of warmth, safety, and simple, incorruptible goodness; and a corresponding universe of enchantment that tends to be quaint and whimsicalunthreateningveering as it does from the imaginations extremes of passion and violence. To have seen the ballets in their native setting, to have experienced something (if only the travelers wonderstruck something) of Copenhagen, is to have penetrated a little further into Bournonvilles unique world.

click here to read more...

| |

Sunday, May 15, 2005

STAYING POWER

Jock Soto retires from the New York City Ballets stage on June 19 at the age of 40, after 25 years with the company. For the latter part of that period he has been extolled as a partneras if that were his main (even sole) virtue, as was, essentially, the case with the companys Conrad Ludlow in the past and Charles Askegard today. Yes, Sotos an astute, often sublime, partner, buthaving been around when he first showed up at the School of American Ballet and set the corridors abuzz with excited whispers: Have you seen the new boy? Down the hall, taking class. Hes amazing !I think back to him as a dancer.

Memory is a tricky thing. Led by sentimentfor an artists personality, for the  terrain on which he operated, for the sheer accumulation of historyit can transform dross into gold. So I looked for more concrete evidence of the qualities I remembered in Soto from the early part of his career and found them, where you can see them too, in a videotape of The Magic Flute, choreographed by Peter Martins for the School of American Ballets Annual Workshop Performances in 1981. It was right after these performances that Balanchine invited the 16-year-old playing Luke, the male lead, to join the corps of the New York City Ballet. terrain on which he operated, for the sheer accumulation of historyit can transform dross into gold. So I looked for more concrete evidence of the qualities I remembered in Soto from the early part of his career and found them, where you can see them too, in a videotape of The Magic Flute, choreographed by Peter Martins for the School of American Ballets Annual Workshop Performances in 1981. It was right after these performances that Balanchine invited the 16-year-old playing Luke, the male lead, to join the corps of the New York City Ballet.

The ballet itself is a charmer. Like Ashtons La Fille mal gardée, the model of the genre, its a romantic pastoral comedy. Martins adds to the mix a commedia dellarte element that he no doubt absorbed in his youth from the traditional pantomimes given in Copenhagens Tivoli Gardens.

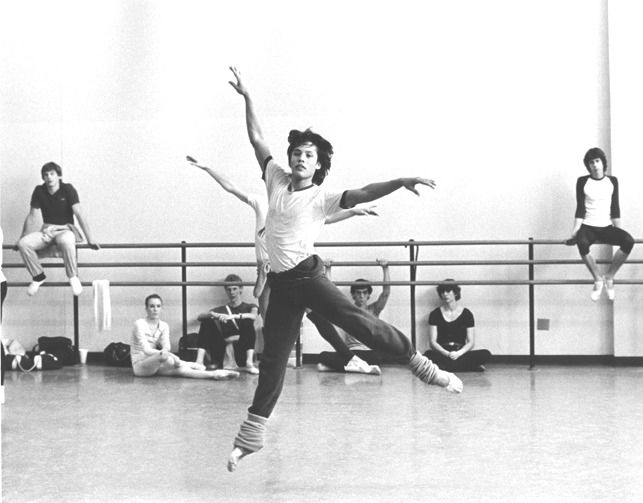

The adolescent Soto recorded here is utterly disarming, and not just because of a frank, luminous smile that is well-nigh irresistible. Of course there are plenty of raw edges in the performance. Hes gawky here and there, unpolished, impetuous, giving himself over to a very simple joy in the moment. You could say hes only a kid, though no adolescent in serious training for a career in ballet can be simply a kid. Granted, theres no sign here of the gravitas that would distinguish Sotos mature work, but the nascent professional is already evident. His placement is very secure and very beautiful. In motion, hes not merely fluid but also extremely, if casually, graceful. His dancing is consistently soft and floating. On take-offs and landings, his feet seem to caress the floor. (After one lovely solo passage, his fellow students, breaking stage decorum, come out of character and applaud him.) He takes his acting responsibilities seriously and carries them out naturally, as if hed discovered that Luke had a personality not too far from his own.

The gift for partnering is apparent, too, lacking only the fine-honed skills and increasingly sensitive intuition that experience would bring. Self-confident, Soto exudes a quiet assurance that, vis-à-vis his partner, he will be in the right place in the right way at the right time. Along with this technical aplomb, he displays an easy sympathy toward his lady (the 18-year-old Katrina Killiantiny, light, and quick) as well as a devotion and respect that might well be termed chivalric. He knows how to frame her, creating an aura around her like a halo, and he knows how to get the hell out of her way. Close-up shots reveal his large, capable hands and strong back. When supported pirouettes are on the agenda, hes an enabler first class. You can see how, even in these early days, he roots his partner, stabilizes her in her most precarious positions and dangerous moves. Hell stand at a slight distancewaiting, alert, readyand then simply move in and become her center.

It should be remembered that it was Martins himself who chose Soto to play Luke. Perhaps he recognized the similarity between them as dancers, both in the buoyant, cushioned solo work and the suave partnering. Theres little physical resemblance between them. Martins was tall, blond, Greek-god beautiful. Soto is of medium height, jet-haired and olive skinned, with an Aztec cast to his features. His build is undeniably stocky, with a larger head and shorter neck than classical ballet, obsessed with harmonious proportion, prefers for its princes. Sotos distinctive anatomy would eventually add to his onstage presence not merely dignity but also intensity, enhancing a key aspect of his temperamenta darkness and ferocity that seized the viewer and refused to let him go.

Now Sotos audience must let him go, with thanks.

For succinct bios of Jock Soto, along with lists of ballets created for him and the many other roles he danced with the New York City Ballet, use these links:

http://www.nycballet.com/about/print_sotobio.html

http://www.sab.org/faculty_soto.htm

Photo: Steven Caras: Jock Soto, rehearsing Peter Martinss The Magic Flute for the School of American Ballets Annual Workshop Performances, 1981

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

| |

Sunday, May 8, 2005

ON WITH THE NEW!

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / April 26 June 26, 2005

One way or another, gala programs must be striking. This season, the New York City Ballets boldly shunned both Balanchine and Robbins, the guys who give the company its raison dêtre, for five new additions to its repertoryall choreographed by current members of the home team. Three of these pieces were duets that could be taken, obliquely, as windows on the state of dance today, at least on NYCB turf, and the state of love in these postmodern times.

Albert Evanss Broken Promise, set to Matthew Fuersts Clarinet Quartet, lets you see whats best about Ashley Bouder: the diminutive, taut bodyfueled by extravagant but implacably controlled energycreating sharp, intensely vivid images in the vast space of the State Theater stage. Her costume, by Carole Divet, suggests what keeps some observers (like me) hesitant about joining her growing fan club. Its a sleeveless, backless, cleavage-baring white leotard gaudily studded with giant rhinestones, and it makes her look like a Russian gymnast whos a sure bet for the gold. At first Stephen Hanna seems to be there only to support her when needed, conveniently disappearing when hes not. Then he gets some of his own high-octane stuff, though its interrupted when she hurtles out of the wings to throw herself at himliterally. Their duets look like physical competitions, sometimes friendly, sometimes hostile, and when the last moves of the dance posit them as lovers bedding down, youre startled to realize that all that previous athletic bravura must now be understood as foreplay. What this piece says about love is that the sedentary among us should hie ourselves to the gym, pronto, or we wont stand a chance.

Benjamin Millepieds Double Aria, first performed by his chamber group, Danses Concertantes, in 2003, takes its name from its musicDaniel Otts Double Aria for Violin Alone. (Choreographer and composer have collaborated several times and are now preparing a piece for the School of American Ballets annual showcase in June.) Double Aria puts the violinist (Timothy Fain) onstage so that hes all the more a partner in the proceedings and, indeed, sometimes a soloist, as the dancers fade in and out of the picture. These dancers are an extravagantly (almost eccentrically) long-limbed pair, Maria Kowroski and Ask la Cour. We see them first, then again at intervals, in silhouette, a tactic that emphasizes their shape, as do the repeated vertical undulations and complex intertwinings Millepied assigns them. Kowroski is subjected by her partner to a certain amount of fling-and-draga tactic that has cropped up frequently in new pieces at NYCB. I suppose nothing personal is implied when the work purports to be abstract, thoughyou know how it issome viewers might just take it personally. The structure of Double Aria wasnt entirely clear to me, but, giving it the benefit of the doubt, and knowing that Millepied is French-born and French-trained, I thought that it might be one of those subtly clever schemes French intellectuals dream up. Waiting for the enlightenment that might come with a second viewing, I enjoyed the air the dance had of being a sketch spontaneously improvised to the seductive meandering of the music. What it tells us about loveor, at any rate, a relationshipis that it neednt engage the soul.

Edwaard Liangs Distant Cries, to a plangent Albinoni score, was first seen earlier this season in the repertoire of the chamber group Peter Boal & Company. Danced here, as it was there, by Boal and his frequent partner Wendy Whelan, it is tinged with the dancegoers knowledge that Boal will retire from performing in June and leave for the West Coast to direct Pacific Northwest Ballet. Liangs choreography and Whelans increasingly sensitive interpretation of her role suggest themes of loss and grief. (The idea of something irreplaceables coming to an end is a particularly big deal at New York City Ballet, going straight back as it does to the death of Balanchine.) Liang uses his dancers wisely, capitalizing on Boals reticence and purity and Whelans ability to look utterly fragile and malleable without fully concealing a fascinating will of steel. The choreography, if not remarkably innovative, is reasonably adept and unaffected, marred only by some inexplicable peculiaritiessuddenly flexed feet in an otherwise classical context and a repeated phrase for the arms that looks as if it should mean something, but doesnt. What it tells us about love is that, no matter how devoted, it doesnt last. Of the messages offered by the three duets, this is the only one to interest itself in tenderness.

Two offerings on the program, by the companys most frequent providers, supplied some expansiveness to contrast with the restricted duet form. In his Tālā Giasma, set to the Estonian composer Pēteris Vaskss Distant Light: Concerto for Violin and String Orchestra, Peter Martins returns to the concerns of his Eros Piano: A manperhaps searching for an elusive ideal love, perhaps merely a passerby distracted in the humdrum course of his lifeencounters more than one alluring but mysteriously remote lady and finds it impossible to opt for this one or that.

This time there are three women (Sofiane Sylve, Darci Kistler, and Miranda Weese), and they appear to be goddesses, or at least nymphs. Sheathed in palely tinted body stockings, they dance in Mark Stanleys delicate dawn light. When the man (Jared Angle, replacing the injured Jock Soto) first comes upon them, they are a benign sisterhood, inclined to lyricism. Once he engages with them singly, their individual temperaments surface. Sylve becomes demonic, thrillingly so. Weese displays an implacable strength, but it is cool and remote, while Sylves vehemence is sensual. Kistler remains gentle and tender, almost pleading with the man to love her, rewarding him, when he responds, in dulcet terms agreeably tinged with pathos. The three come and go, with the man expressing his confusion (or is it frustrated longing? or dismay?) in solo passages, then masterminding a final quartet. Still he never arrives at a choice, and the ballet ends with him standing behind the womens recumbent bodies, his arms raised toward the heavens.

The choreography makes much of the womens extravagant extensions and some sudden, dramatic drops from a supported position on pointe to the floor, as if to claim that modern-dance turf for classical ballet, which traditionally adheres to an aristocratic verticality. Otherwise, its pretty much business as usual, including the quotes from Balanchine. Here theyre mostly from Apollo (about another fellow who comes upon a trio of lovelies) and are far too many and too literal, co-opting verbatim text only to sully it. It might also be observed that Balanchine has his hero make a clear selection among the three muses, so there can be a central duet that is key to the firm shape of the ballet. Martinss piece seems too long, I think, because it is diffuse.

Tālā Giasma also connects, obviously, to Nijinskys LAprès-midi dun faune and, not so obviously, to Bournonvilles A Folk Tale, in which, long ago as a young principal with the Royal Danish Ballet, Martins played the hero, Junker Ove. On the surface the golden youth of everyones dreams, Ove is nonetheless a troubled soul, at odds with his destined brideand rightly so; she turns out to be a troll. He eventually meets his proper matchall sweetness, light, and purity of heartbut not before he has been set upon by the supernatural Elf Maidens (cousins, you might say, of the wilis in Giselle) whose first appearance, rising from a trapdoor in a dense fog, is as a single woman who suddenly, terrifyingly, morphs into three. Im not saying Martins was consciously thinking about A Folk Tale when he made Tālā Giasma; Im saying that what one has seen and done remains irrevocably a part of ones equipment.

Christopher Wheeldons An American in Paris, the only new piece on the program to boast décor and a sizeable cast, was no doubt an attempt to send em home entertained. Despite the blandishments of the Gershwin score, I slunk home depressed at the conspicuous emptiness of the dance and worried about the possibility that Susans Stromans Double Feature, which reportedly sold a good many NYCB tickets last year, might be evolving into a regularly used genre, in which a popular vintage movie is co-opted for vacuous shenanigans. Balanchine was no fool. He understood the need for a cheerful program closer. To fill this slot he created ballets like Western Symphony, which was colorful and lighthearted andfor people who cared about that sort of thinghad real choreography. Wheeldons effort has innumerable reference points, four drops by Adrienne Lobel ( faux-Cubist takes on tourists Parisa Seine-side quay, the picturesque rooftops, et al.), and lots of pointless agitation.

Damian Woetzel, playing Gene Kelly, gets to mingle with the requisite generic types of Paris in the fifties: pert jeunes filles; young matrons in straw hats and gloves; anonymous guys in berets; a lady of the night; several gendarmes; a nun and her Madeleinesque charges (only three, so the twelve little girls in two straight lines effect was blown); and a cyclist (on his machine) taking a break, no doubt, from the Tour de France. He also gets to dance a bluesy duet with his sweetheart-in-pink (Jenifer Ringer, who curls around him like a kitten) and enjoy a little encounter on the side with an adorably saucy Carla Körbes, who emerges from a unisex gang of street toughs. None of this has any originality as dancing. And then we find out (surprise! surprise!) that it was all a dream. After raiding the film for a few basic situationsand failing to develop themWheeldon still counts on our transferring our nostalgic affection for the movie to his pallid show. Gimme a break!

Photo: Paul Kolnik: Jenifer Ringer and Damian Woetzel in Christopher Wheeldons An American in Paris

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

| |

|