“There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.” So says Oscar Wilde. Is he right?

A new issue of the British Journal of Aesthetics has arrived in my mailbox, and the October 2022 issue is devoted to the question(s) of art and morality, including discussion of four recent books: Mary Beth Willard’s Why It’s OK to Enjoy the Work of Immoral Artists; Ted Nannicelli’s Artistic Creation and Ethical Criticism; Erich Hatala Matthes’s Drawing the Line: What to do with the Work of Immoral Artists; and James Harold’s Dangerous Art. I’m looking forward to reading the symposium when the semester is done.

I find these are challenging topics to teach. Our arts management students need to have thought about these issues, since, as any regular reader of artsjournal.com knows, arts-presenting organizations are often called upon to make decisions about what to do about problematic works or art, or artists who themselves are, as they say, a piece of work.

I divide the question into three parts. I start with the more abstract question of whether one can or should separate the aesthetic qualities of a work of art from any underlying ethical issues in its narrative. Can the artist’s treatment of race, gender, violence and cruelty, be so cavalier or wrongheaded that it cannot help but affect any distanced appreciation of the artist’s craft? Here I find Noel Carroll’s essay on “Moderate Moralism” the best introduction for students to the question.

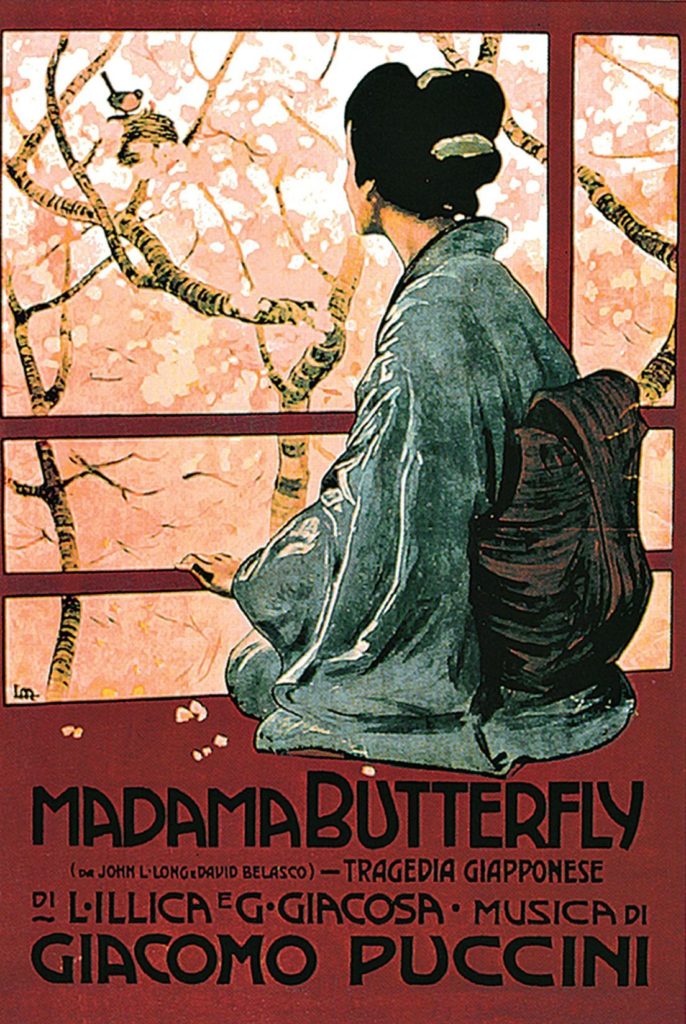

I then move on to the question of what the arts manager is to do with great, but problematic, works. Note the word “great”: if the art is simply not very interesting, then there isn’t really a question – no need to have it in the program. But if there is a work that has long been hailed as great, and contains within it real beauty, what then? Proceed as usual, or cut it from programming, or present it as a special case, with attempts to communicate to the audience why the work is problematic but why it is being presented in any case? And can the latter be done without patronizing the audience, lecturing them as if they were little children?

The third question concerns the problematic artist, and what to do with his (in my experience, it’s always been a “his”) works, even when the works themselves are great and do not present questionable ethical views. Sometimes my second and third questions can overlap (for example).

These questions are difficult to teach for a few reasons. One is that you cannot simply work in the abstract: if a work has racist elements, if a work eroticizes sexual violence, then one needs to see how, and that can, for some students, involve some genuine hardship. I try to give lots of advance warning to what’s going to be up for discussion, and to not require attendance or participation, or explanation, for any student who wants to be excused.

A second reason is that students are, quite understandably, reticent, very cautious about putting a foot wrong, being judged as insensitive (or over-sensitive). Here I try to draw them out by admitting sincerely to my own uncertainties surrounding these questions.

In the end, I try to help them see there is no formula to be applied – every work, every time and place and audience and company, are unique, and require a weighing of factors. There is no, to use the education-bureaucrat’s phrase, “learning outcome” here. Just an exercise in judgment and empathy.

Leave a Reply