At the college where I teach I’ve recently had some interesting experiences with the concept of nonviolent communication. The term was coined by psychologist Marshall Rosenberg some forty years ago, the result of his experience as a civil rights activist and his continuing interest in peace work. According to the Center for Nonviolent Communication website,

Nonviolent Communication (NVC) is based on the principles of nonviolence—the natural state of compassion when no violence is present in the heart. NVC begins by assuming that we are all compassionate by nature and that violent strategies—whether verbal or physical—are learned behaviors taught and supported by the prevailing culture. NVC also assumes that we all share the same, basic human needs, and that each of our actions are a strategy to meet one or more of these needs.

What gets in the way of our natural proclivity for compassionate behavior is fear. When people feel unsafe inside a conversation, they retreat to one of two places: silence (overt resistance) or violence (communication behavior that harms others).

A quick google search identifies NVC applications in business, parenting, education, mediation, psychotherapy, healthcare, the penal system, social change organizations and peace/conflict negotiation.

There is no mention of a NVC application to the arts.

Not a surprise, of course, since we don’t usually think of communications around the arts as an area of potential conflict. But actually, I think we should. Psychological/emotional safety is a big issue when it comes to audiences being willing to talk publicly about the meaning of the serious arts.

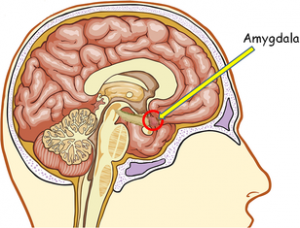

In all our human experience, our sensory signals are first routed through the amygdala (the fear/danger center). According to biologist and educational theorist James Zull, “This so-called ‘lower’ route begins to make meaning of our experience before we have begun to understand it cognitively and consciously. Our amygdala is constantly monitoring our experience to see how things are.”

When an experience is demanding or strange, the emotions tied up with the learning process, first filtered through the amygdala, will be felt as a form of danger. As we know from our own personal experience, when fear and/or danger is triggered, we act differently.

Exposure to a new kind of art can become rife with fear when we sense that we are out of our comfort zone, about to be challenged intellectually, or are facing a confrontation of some kind—for example, a debate based on a person’s taste and/or the value of a particular style or type of art. In this context, the amygdala triggers the fight-or-flight response. Even when we choose not to take part in a literal fight (violence), we often convert our fear into a kind of flight (silence), as in, “I’m not going to say anything during this audience talk back session because I’m sure I’ll just be wrong anyway.”

In the practice of Nonviolent Communication, there are two conditions for safety: mutual purpose and mutual respect. I can’t help but wonder about the application of these conditions to the way in which we talk about the arts in contemporary America.

I’m going to keep thinking and reading about it and would be happy for your thoughts as well.

[…] Beyond Museum Walls: A Driving Tour AJBlog: Real Clear Arts | Published 2014-04-29 Silence or Violence AJBlog: We The Audience | Published 2014-04-29 Public support for the arts and the letter of the […]