The new issue of the online New American Studies Journal is devoted to the challenged fate of the arts. I append an overview of my contribution on “The Erosion of the American Arts.” To read the whole article, click here. To see the whole issue, click here.

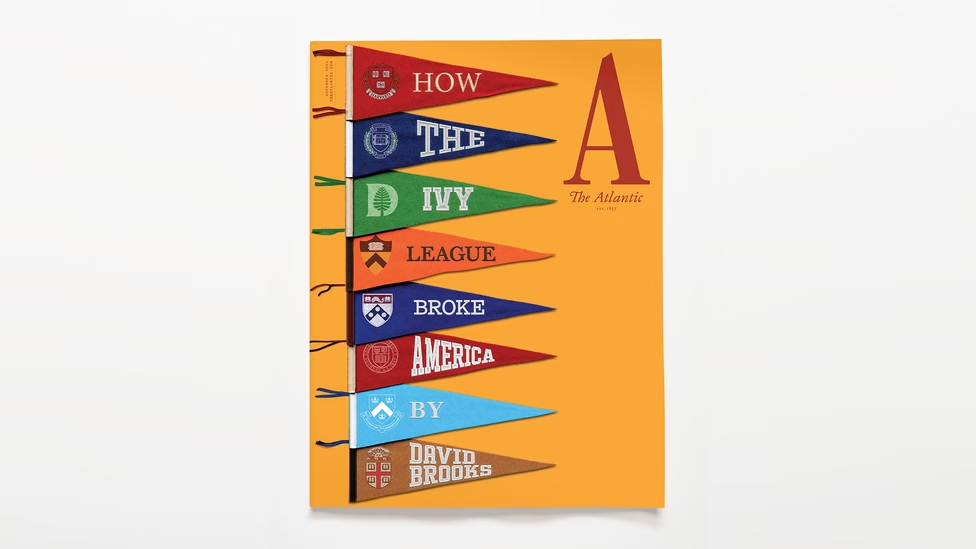

The gripping cover story of the 2024 December issue of The Atlantic is “How the Ivy League Broke America.” David Brooks, its distinguished author, characteristically adapts a purview broader, more based in political and cultural memory, than that of other pundits. Here, he applies a fresh historical perspective to our current national crisis, arguing that an exaggerated emphasis on intellectual aptitude, traceable to the educational priorities of Harvard President James Conant (1933–1953), fostered a new “meritocracy”—an American ruling class defective in other human virtues. “Is your IQ the most important thing about you?” Brooks asks. He answers: “No. I would submit that it’s your desires—what you are interested in, what you love. We want a meritocracy that will help each person identify, nurture, and pursue the ruling passion of their soul.”

Brooks is addressing the rampaging malaise that all acknowledge—friendlessness and depression; opioid addiction and rage; political and governmental dysfunction. The diagnoses he adduces (packed with social science statistics) are more compelling than the remedies he glimpses. And one obvious source of remediation is hiding in plain sight: Amid a dozen pages of dense argumentation, Brooks only once drops the word “art.” And yet, it seems to me obvious that a rapid erosion of the American arts as previously experienced—in child-rearing, education, and higher education; in civic identity; in media and social media; and in our daily lives—is a crucial impediment to nurturing “what you love” and pursuing “the ruling passion” of the soul. And I find myself ever more mindful of how fundamentally exposure to the arts has diminished during my own lifetime.

A tidal continuum submerging the arts with entertainment may be traced in stages from silent film to film with sound, then color; to TV with its laugh and applause tracks: to youtube, with its loud and irrelevant ads; to social media and the segmentation of Americans into consumers of political and cultural pabulum. The ease with which entertainment pays commercial dividends, the alacrity with which it can today be produced and acquired, are fatal enticements. At every stage, engagement grows ever more supine.

Are these impediments deeply rooted in the American experience, even within the very ethos of democracy and freedom? Certainly there is an impressive lineage of writings analyzing an American aversion to artists and intellectuals. An enduring philosophical argument against the American arts was launched by Theodor Adorno and the Frankfurt School. Much more recently, positing “a new theory of modernism,” the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa calls the governing dynamic “social acceleration” – and his prognoses are grim.

With so much at stake, where does hope lie? Contrary to what might be thought or assumed, it cannot be said that America was never a fit home for the arts. During the Gilded Age, no one pondering issues of shared American identity would consider omitting the arts. In the decades after World War I, the arts were more widely but also more superficially acquired.

In my essay, I emphasize the possibilities for innovation in his own field: orchestras. They were once an American bellwether. Two recent controversies drive home the moment – the resignation of Esa-Pekka Salonen as music director of the San Francisco Symphony, and the engagement of Klaus Makela as music director of the Chicago Symphony. Curating the American musical past, comparable to the efforts of art museums, remains unattempted. A case in point is the Charles Ives Sesquicentenary, ignored by the major US orchestras.

Brooks makes an equivalence between desire and love. They are not. Desire is inner-directed. Love is outer-directed. Desires are sated. Love is requited. Fulfilling desires and needs is the ultimate business of capitalism. When our desires and needs are conditioned to be met by consumption, the bonds between us fray and break.

Love is about communion, connection. It cannot be bought or commodified. Art is a kind of engagement with the world–its sounds, spaces, movements, actions, beings–and is a manifestation of love of the world and how we understand it and our place in it.

Oligarchs and dictators hate art because it eludes control–or it can, anyway. I think of Neruda’s poem, The Poet’s Obligation.

So, drawn on by my destiny,

I ceaselessly must listen to and keep

the sea’s lamenting in my consciousness,

I must feel the crash of the hard water

and gather it up in a perpetual cup

so that, wherever those in prison may be,

wherever they suffer the sentence of the autumn,

I may be present with an errant wave,

I may move in and out of the windows,

and hearing me, eyes may lift themselves,

asking “How can I reach the sea?”