Today’s online Persuasion magazine carries my thoughts on “The Tangled Legacy of JFK and the Cultural Cold War: America Needs a New Public Policy for the Arts.” You can read it here.

Bottom-line, I write: “If, logically, American arts policy today should focus on greatly increasing government support at every level, never has this prospect seemed less likely. Now, too, is a logical moment for top-down cultural diplomacy to soften and inform relations with at least some governments deemed hostile or intractable.”

Here’s a longer extract:

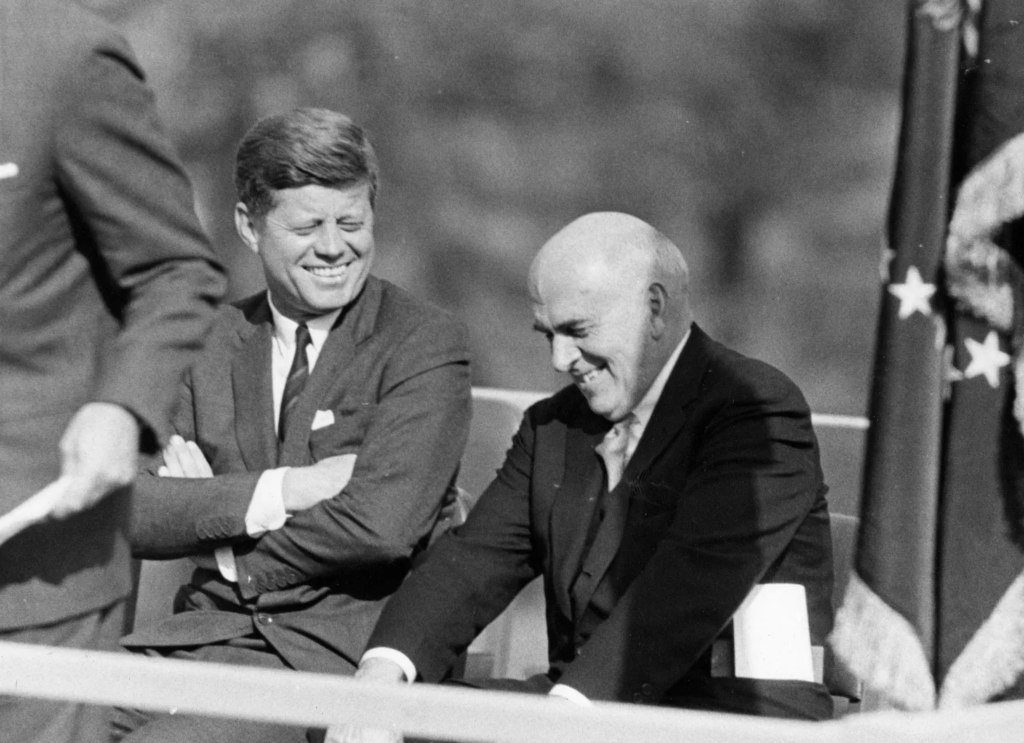

It is little-known that, when he died, President John F. Kennedy was about to appoint Richard Goodwin – a vigorous member of his inner circle – his advisor on the arts. Kennedy’s initiative would have vitally supported the ongoing cultural Cold War with Soviet Russia. Something like it is ever more necessary today. The American arts – as will increasingly become widely apparent – are in crisis. And the United States, incongruously, still possesses no Ministry of Culture.

Kennedy’s arts advocacy was surpassingly eloquent. . . . At the same, time, however, the White House’s eagerness to host the likes of Igor Stravinsky and Pablo Casals was mired in Cold War rhetoric. The central dogma of the cultural Cold War, as pursued by the United States Government, was the notion that only “free artists” in “free societies” produce great art – a plainly unsupportable claim. . . .

That the “propaganda of freedom” cheapened freedom by overpraising it, turning it into a reductionist propaganda mantra, is one measure of the intellectual cost of the Cold War. . . . It also prejudiced Kennedy against government arts subsidies – lest artists discover themselves pushed and prodded by the state. And this prejudice lingers.

We are today witnessing an erosion of the arts far beyond the arts challenge that worried Kennedy. . . .

Where will new funding arise? . . . Though the need for government support is now self-evident, though the American experiment in laissez-faire arts support can by now be pronounced a failure, there is no political will to create an Arts Council on the European model. We have no Jacob Javits or Claiborne Pell in Congress, no Nancy Hanks at the NEA. Social justice activism has fractured the arts community at a crucial moment. Widespread public awareness of the arts as a necessary component of a nation’s life remains mainly apparent abroad. If, logically, American arts policy today should focus on greatly increasing government support at every level, never has this prospect seemed less likely. Now, too, is a logical moment for top-down cultural diplomacy to soften and inform relations with at least some governments deemed hostile or intractable. . . .

An indispensable Cold War asset, cultural diplomacy concentrated JFK’s vision of a more civilized nation. But reductionist misunderstandings of the arts – as ambassadors of “freedom” or instruments of social justice – ultimately disserve America’s vital interests, whether at home or abroad.

To read a related article on why the arts and social justice are strange bedfellows, click here:

For more about “The Propaganda of Freedom,” click here:

I think of the JFK quote below, the fine ethos of the Camelot administration, and how it masks the quasi oligarchic sensibilities of an extremely wealthy family’s views:

“Artists are not engineers of the soul. It may be different elsewhere. But democratic society — in it, the highest duty of the writer, the composer, the artist is to remain true to himself and to let the chips fall where they may. In serving his vision of the truth, the artist best serves his nation. And the nation which disdains the mission of art invites the fate of Robert Frost’s hired man, the fate of having ‘nothing to look backward to with pride, and nothing to look forward to with hope.’”

Artists are indeed often engineers of the soul. It is so plainly obvious that “man creates art and art creates man,” as the old phrase goes.” Through culture we create and develop our identity as individuals and societies; we elevate ourselves and create deeper concepts of humanism and all that goes with it such as concepts of justice and social organization. The arts lead us to search for what it means to be a human.

We thus see what the suppression of the fine arts has does to our country. Our political systems have become crude and debasing. Our social cohesion has been almost entirely fragmented. Our concepts of rule by law have been weakened. Our sense of self as a country has been lost. Our religions have been corrupted. The humanistic values of knowledge, wisdom, compassion, and care are demeaned.

The idea that evolved beginning in the 1980s of stressing STEM subjects at the expense of the arts gradually dehumanized our system of education and thus our society. It is difficult to overlook that this debasement so well symbolized by Trumpism directly serves the interests of our radically unmitigated system of capitalism with its Darwinist view of humans and their societies. We are to be stripped to a raw, surveilled, socially engineered consumerism and little else.

Historically, we see that most great scientists were also highly cultured and immersed in the arts. They would have never defined education as an either/or divide between the arts and the sciences. Einstein is a famous example. He considered music an essential part of the intuitive processes through which he developed his scientific understanding. And even more, an essential part of what makes us human.

Arts funding in the era of Trump? Really? I’m guessing that if he can, this current president will abolish the National Endowment for the Arts, not build it up.

As for JFK’s arts advocacy, I seem to remember that Mrs. Kennedy was the real pusher for the arts in the White House. I remember that when Philharmonic Hall opened and they had the big gala concert with the NY Phil, Lenny, a galaxy of star performers, and a Copland world premiere, Only Jackie was there, her husband being noticeably absent.

I’m 79 so won’t be around for a whole lot longer, and I really hope there will be a renaissance of interest in all the arts, but right now I’m not optimistic for anything like that happening in my time.