Today’s online edition of “The American Scholar” carries my essay on Lawrence Tibbett and how he “prophesied today’s Metropolitan Opera crisis.” You can read it here. An extract follows:

In a recent New York Times “guest essay,” Peter Gelb, the Metropolitan Opera’s embattled general manager, expresses the naïve hope that “new operas by living composers” can make opera “new again.” And he blames critics for being “negative or at times dismissive.” In fact, recent Met seasons have highlighted operas in English composed by Americans. But they’re all recent (the Met still ignores Marc Blitzstein’s Regina [1948], arguably the grandest American opera after Porgy and Bess) and debatable in merit. Works like Terence Blanchard’s Champion and The Fire Shut Up in My Bones, however touted today, will not endure: their craftmanship is makeshift; there is no lineage at hand. And the standard repertoire is increasingly hard to cast with singers capable of projecting musical drama into a 3,850-seat house. In fact, the vast Met auditorium is today an albatross, an emblem of financial duress and artistic crisis.

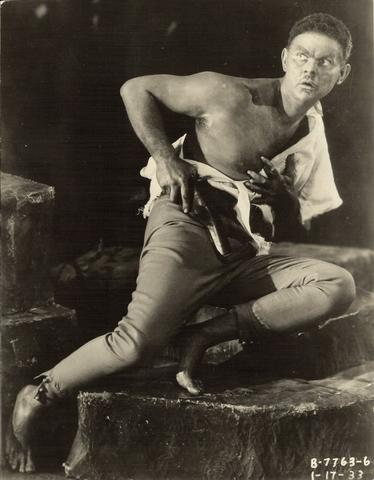

Of all the many might-have-beens, among the most tantalizing involves Lawrence Tibbett, who seemed a candidate to take over the Met in 1950 – the year an Austrian, Rudolf Bing, was appointed general manager. Though retired from the stage, Tibbett was still widely famous, arguably the foremost singing actor ever produced in the US. As a Verdi baritone, he had more than held his own with pre-eminent Italians. He had starred in Hollywood and on commercial radio, had sung many dozens of recitals annually in cities of every size. American-born, American-made, he embodied a pioneer archetype.

And, no less than Henry Krehbiel [who wrote that opera in the US would remain “experimental” unless and until American works were promoted and embraced], Tibbett was prophetic. He declared opera in America “in grave danger,” entrapped by a “star system” enforced by a social elite. He advocated American opera and opera in English. He urged the substitution of smaller auditoriums, shedding the glamour of opera houses in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco far exceeding in scale European norms. He resisted touring abroad or Italianizing his name. He called for financial incentives for American opera composers. He wrote that “the whole structure of opera must by Americanized if Americans are to support it in the long run.” Ignoring a critical consensus marginalizing George Gershwin as a dilettante, the claimed that Rhapsody in Blue surpassed “in real emotional musical quality half of the arias of standard operatic composers whose works are the backbone of every Metropolitan season.” Singing Gershwin and Cole Porter, Sigmund Romberg and Jerome Kern, singing Lieder in English, he embodied a democratic range of style and repertoire decades ahead of the game. A voluble public advocate, he thundered: “Be yourself! Stop posing! Appreciate the things that lie at your doorstep!”

To access an NPR “More than Music” episode about Lawrence Tibbett, American opera, and “singing Black,” click here.

There’s a story — perhaps apocryphal?? — that Tibbett wanted to give one of his recordings as a gift to a friend and went to a local record store to buy it. The clerk told him that no such recording existed. Tibbett said: “I am Lawrence Tibbett and I made that recording.” The clerk replied: “We thought you must be French so we pronounced it ‘Tee – Bay.'”

While opera houses may not have taken Tibbett”s advice, the art form of opera as an authentically Amrican product has borne fruit in our great tradition of music theater. The works of Sondheim represent American opera’s zenith. It’s short-sighted to see what opera houses are performing and conclude that American opera has missed the boat or failed. Let’s also remember that the vast majority of operas “fail” in the sense of becoming popular; popularity and success are not synonymous. Not in art.

>>> “popularity and success are not synonymous. Not in art.”

Wasn’t it Schoenberg who said:: “If it is art, it is not for all, and if it is for all, it is not art.”

It’s ironic that as one -time president of AGMA, Tibbett didn’t (or couldn’t) foresee that the cost of putting on opera with a unionized staff pretty much forces one to have large audiences in order to cover costs. I’m very pro-union, but unless one is working with non-union amateurs, the economics of producing opera (or even symphony concerts with a near-full orchestra) dictate that one must have a sizable audience.

Perhaps the problem of “American opera” is not so much its foreign origins, but the lack of political and cultural support. In Europe, generally people know that these works are part of their culture, even if they don’t care to attend performances. I think that’s part of the reason why so many European countries provide some support to the arts. In the U,S. all music is regarded as entertainment which means that it is not essential to living life. When you have politicians who are in favor of eliminating any support for the arts, they convince the public that spending money on the arts are a misuse of money – which encourages hostility toward the arts and anyone attending them.. Thus the arts are forced back into the patronage formula.