If you’re in the mood for a rollicking conversation about the downfall of classical music in the US, check out this podcast conversation I recently had with the terrific conductor Kenneth Woods (who’s based in the UK rather than the US, in which he deserves a music directorship of consequence).

My favorite sentence:

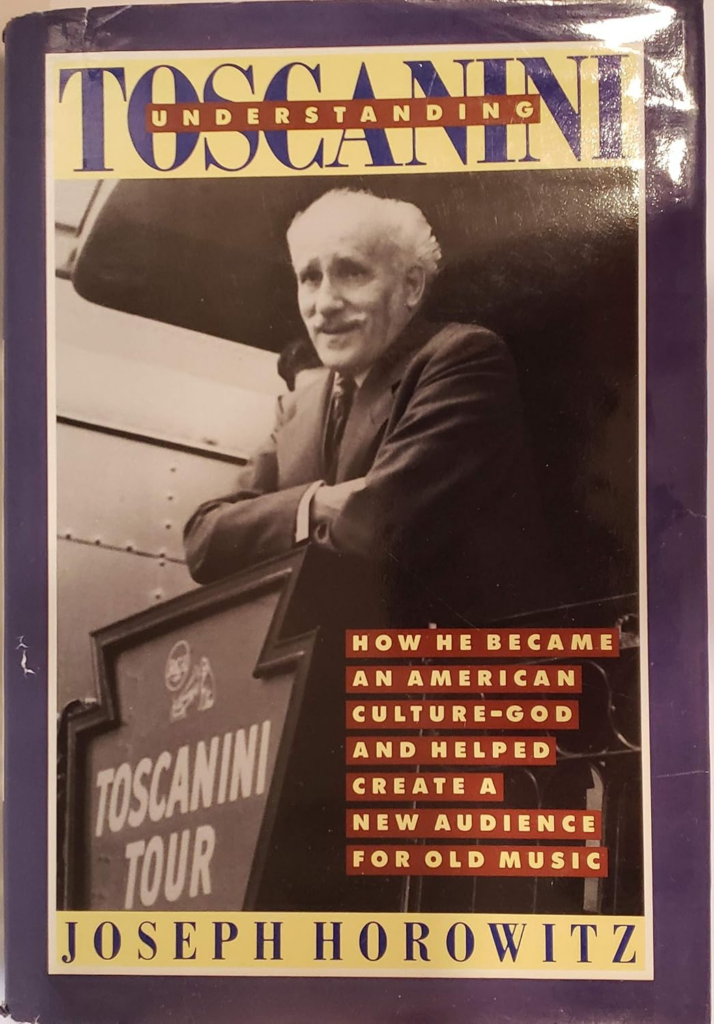

“Those chickens that are now coming home to roost are the chickens I’ve been writing about since the 1980s [in Understanding Toscanini], for which I was initially vilified. But now that I’ve turned into a prophet, I’m simply ignored.”

These, in sequence, are the topics at hand:

1.The grim situation of the arts in the UK right now: no money.

2.My visit to South Africa, and how classical music there is evolving with notable Black leadership (thanks in part to Nelson Mandela).

3.My ruthless analysis of the interwar popularization or “democratization” of classical music in the US, which anointed Arturo Toscanini “the world’s greatest musician” even though he wasn’t a composer. This was a commercial operation headed by David Sarnoff (RCA/NBC) and Arthur Judson (the managerial powerbroker who declared that “the audience sets taste”). Dead European masters — easiest to merchandize — were prioritized. Amateur music-making was discouraged in favor of broadcasts and recordings by the experts.

4.A barrage of pointed questions and observations from Ken attempting to figure out Toscanini’s primacy (“why he won”). Toscanini’s appeal to mass taste.

5.Ken proposes a thought experiment – subtract Toscanini from the story of classical music and what do you get? You get Serge Koussevitzky and Leopold Stokowski. And where might that have led? I marvel in passing: “Stokowski didn’t care about integrity, it wasn’t part of his vocabulary.”

6.Dmitri Mitropoulos, and why his 1940 Minneapolis Symphony premiere recording of Mahler’s First seems to me the most remarkable Mahler recording ever made – and unthinkable today (with choice audio examples)

7.Ken asks: What if Leonard Bernstein had been appointed Koussevitzky’s successor in Boston in 1950, rather than winding up at the New York Philharmonic (which had no pertinent tradition of espousing American music)? Ken answers himself: “It would have changed the repertoire of all American orchestras.”

8.My own favorite thought experiments:

— What if Gustav Mahler had premiered Ives’s Second Symphony with the New York Philharmonic?

— What if George Gershwin had lived as long as Aaron Copland?

Either would have fundamentally changed the trajectory of American classical music.

9.What if Anton Seidl – who was bigger than Toscanini or Bernstein in New York City – had not died in 1898 at the age of 47? There would have been an annual Wagner festival in Brooklyn as pedigreed at Bayreuth – limiting the damage inflicted on Wagner by Hitler and Winifred Wagner.

10. “I can’t imagine life without cultural memory, although we’re beginning to get a glimpse.” Today’s “makeshift music,” sans lineage or tradition – “eagerly acquisitive and open-eared.”

Today’s famous instrumentalists sans lineage or tradition –vs Sergei Babayan and Daniil Trifonov, who perform Rachmaninoff “in full awareness of a tradition of Russian composition and performance.”

11.The Metropolitan Opera’s “worst ever” Carmen

12.Leonard Bernstein’s capacious vision, revisited today.

Fascinating and thought provoking, as ever. I have appreciated your writings for years, and even more so now, as beacons to navigate through this current, mindless, cultural maelstrom. Please keep the lamp lit. Thanks.

With all due respect , I. reject the premise of the book “Understanding Toscanini ” . Yes,, he concentrated on. the established favorites of the orchestral repertoire with the NBC symphony , but this did not have an adverse effect on classical music in. the US .. Since the death of Toscanini in 1957 , American orchestras have played countless new works by a wide variety of composers , including women , black, Asian and Asian-American composers etc and. new works by American composers are still performed on a regular basis .

And it should be remembered that Toscanini was a staunch champion of new music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries , and conducted the world premieres of new operas by Puccini , Leoncavallo , and other Italian composers and. was a champion of. orchestral music by Respighi, Busoni , and other Italian composers. who are. little known today . Also, non-italian composers of his day . It was only as a world famous elderly conductor in his years with the NBC symphony that. Toscanini began to concentrate on the warhorses of the orchestral repertoire . But he still did a number of works by the contemporary composers of the day, if not the music of. Schoenberg, Berg , Webern and other avant-garde composers , whose works he felt absolutely no affinity .

And with all due respect , the final chapter of. “Understanding. Toscanini “, with its. blanket dismissals of. great conductors such as Sir Georg Solti , who did not neglect new music at all with the Chicago symphony turns the book into a giant non-sequitur . ..

Agree 100%

One can add one or two more questions to this “what if”? situation regarding classical music in the US:

1) What if William Paley had not discontinued the CBS Symphony Orchestra and left Bernard Herrmann in charge? Herrmann, who was the modern antithesis to Toscanini’s more traditional programming at NBC, had already introduced American audiences to Charles Ives and other American composers in addition to a sizeable amount of British composers as well as forgotten ones of the 18th and 19th centuries? Would Herrmann had found his life-long dream of becoming a conductor come true instead of being routed to Hollywood where he found himself after the disbandment of the orchestra and became renowned for his innovative film scores?

2) What if one of the American orchestras took the chance and bucked the tide by offering Dean Dixon a directorship of one of the major orchestras? The two factors against him, namely his race as well as appearing on McCarthy’s blacklist, took Dixon to Europe where he would be welcomed and honored for his conducting, but if he had become the music director even of a secondary American orchestra would this have changed the atmosphere of classical music for the better and encouraging more Black Americans to fulfill their aspirations in the field two decades earlier?