George Gershwin chose Lawrence Tibbett to make the first recordings of Porgy’s songs from his opera Porgy and Bess. But Tibbett did not sing them at the Alvin Theatre – Todd Duncan (called by Gershwin “the Black Tibbett”) did. Gershwin wanted a Black Porgy onstage, and Tibbett was white. He was also the supreme American operatic baritone of his (or any other) time.

An extraordinary new 10-CD set issued by Marston Records celebrates the art of Lawrence Tibbett – and so does my most recent “More than Music” feature on NPR. The diversity of his achievement is staggering. And his many recordings in Black dialect are something to think about. In the opinion of John McWhorter, on my NPR show: Given Tibbett’s pre-eminence as an American baritone, given his capacity to inhabit a role and excavate feeling, given his dedication to opera in English, the role of Porgy “was almost written for him.”

McWhorter’s recent New York Times columns include one on “Black English Doesn’t Have to Be Just for Black People.” He takes issue with critics of the comedian Matt Rife, who’s always “dipping into Black English.” McWhorter writes: “Rife is not posing or ridiculing; he’s connecting. Linguists call it accommodation.” The subtlety of McWhorter’s argument resists summary here. But it’s pertinent that Tibbett, too, is “not posing or ridiculing.” Just have a listen to his 1935 version of “Oh, Bess Oh Where’s My Bess?”

McWhorter’s NPR commentary continues: Though the notion that “white people should be allowed to sing like Black people” was “once OK,” today a white baritone singing and acting “Black” would “be hunted to a different planet.” This type of thinking, McWhorter argues, should be “reconsidered” – Tibbett singing Porgy embodies “an American artform evaluable in itself [that] need not be seen as mocking.”

As McWhorter happens to be a professional linguist, I asked him the most obvious question. He answered that, in the context of linguistic practice in 1935, Tibbett “sounds authentic to me. . . . He sounds to me like an educated Black person singing in a sincere ‘dialect idiom,’ . . . adopting a dialect in the same way an opera singer is trained to sing with a proper German accent. . . . If we told a modern skeptical Black critic to listen to one of those [Tibbett] cuts, and we told him it was a Black person, I doubt if one out of one hundred of them would be able to smoke out that they were actually listening to a white man.” Nearly half a century after the premiere of Gershwin’s opera, it’s come time “to just listen to Tibbett as a human being,” opines John McWhorter.

I’ve called my show “’Wanting You’: The Art of Lawrence Tibbett,” referencing an American operetta chestnut, a baritone blast today mainly associated with the likes of Nelson Eddy: hearty and synthetic. Tibbett’s rendering of this Sigmund Romberg number – which he frequently sang on the radio and in recital coast to coast — attains a startling emotional veracity. I invited Thomas Hampson – today’s most famous American baritone – to have a listen. Hampson said: “Quite frankly, this may be some of the most perfect singing I’ve ever heard in my life. It’s just breath-taking. I know the song, I’ve sung it, it’s no walk in the park . . . And the way he negotiates, just technically, this expansive expression, but also with the beauty of tone . . . I mean, my goodness me, what a sound! And to think that this is what was cherished.”

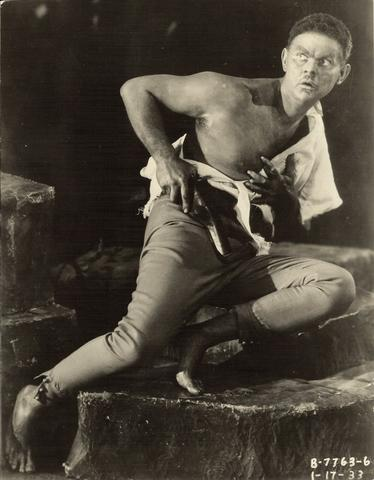

Tibbett craved the role of Porgy. But it was Gershwin’s preference that Porgy be sung onstage by a Black cast – and the Gershwin Estate has maintained this prohibition, at least in the US. Late in his career, in 1953, Tibbett was signed to sing Porgy in Europe. But by then his voice was shot and he had to withdraw. He did, however, sing two roles at the Met made up as an African-American: the Black fiddler Jonny in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf, and – a signature part – Brutus Jones in Louis Gruenberg’s operatic adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones. Fleeing through a jungle, pursued by rebels, Jones sings “Standin’ in the Need of Prayer.” Tibbett left an overwhelming 1934 studio recording of this number. Harry Burleigh, for a time the leading African-American concert baritone, heard Gruenberg’s opera and wrote appreciatively to Tibbett. Tibbett wrote back: “Of all the letters of praise I received, yours means most to me, you who stand so high in the esteem of the Colored race, as well as in the esteem of my own race. You saw the inner significance of the work, and that was lacking in most everyone else’s analysis.”

On Marston’s Tibbett set, and on my radio show, you can also hear Tibbett singing “Scottish” and singing Cockney, singing in French, German, and Italian, inhabiting a bewildering range of personalities and genres. “He had a chameleon-like ability, almost at a genius level, to take on . . . major identity changes,” says Conrad L. Osborne, for more than half a century the pre-eminent English-language authority on opera in performance. On part three of my show, Osborne (who contributes a terrific 60-page booklet to the Marston box) ponders at length what makes Tibbett’s story quintessentially “American.” His training was ad hoc and sui generis; he never studied abroad. Born in Bakersfield, California, he was the son of sheriff killed in a shoot-out when he was seven. His very vocal timbre, Osborne suggests, conveyed an American “call” kindred in spirit to the “lonesome cowboy.” In fact, not only did Tibbett sing cowboy songs; he worked as a ranch hand. This range of experience mattered.

Among the big finds in the Marston set, calibrating the range of Tibbett’s genius, is a 1937 Chesterfield Hour performance of Cole Porter’s “In the Still of the Night.” He’s not just a big voice vacationing from opera. This rendition is as personal as Frank Sinatra’s or Ella Fitzgerald’s. It’s unique to Tibbett – his way with words, his vocal opulence, his huge dynamic range. The song was brand new in 1937, by the way – Tibbett is pitching it.

As memorable, in Marston’s set, is a 1937 Chesterfield Hour performance of Jerome Kern’s “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” Tibbett also frequently sang on the Packard Hour, the Ford Sunday Evening Hour, the Telephone Hour, the General Motors Hour, the Voice of Firestone. That is: on national commercial radio programs hawking cars, cigarettes, and automobile tires, he regaled a mass audience with opera, operetta, and the Great American Songbook.

To my ears, Tibbett is unexcelled in what may be the quintessential Italian lyric baritone aria: “Di provenza” from Verdi’s La traviata. In the Marston set, you can hear him sing it on the Chesterfield Hour. You can also hear him sing it in live performance at the Met in 1935: the cradling legato of his dark baritone, its freedom of phrase and of cadential punctuation, are galvanizing. Singing in German, he’s also the most compelling exponent I know of Wolfram, in Wagner’s Tannhauser. That’s opposite Lauritz Melchior at the Met in 1936. If you happen to be familiar with this opera, check out the third act’s linchpin moment, when Wolfram’s unexpected compassion ignites Tannhauser’s confessional Rome Narrative; Tibbett’s expression of empathy – at 2:36:00 here — is so believable that the incredulity of Tannhauser’s gratitude seems wholly unrehearsed.

I close my radio commentary on the art of Lawrence Tibbett with a “final thought” that “feels so presumptuous that I’m almost reluctant to confide it” —

“We tend to think of human nature as a constant – generation to generation, the same or similar thoughts and feelings. But in recent decades – decades of laptops and cellphones and social media – changes in human predilection are kicking in at exponential speed. When you consider Lawrence Tibbett’s exceptional popularity – on radio, in Hollywood, in opera, in recitals in halls large and small across the United States — re-encountered, he bears witness to another time. Sure, we’ve always expressed, or cloaked, our feelings differently, from one moment, or from one epoch to another. But some of those feelings may actually wither away. Listening to Tibbett sing Cole Porter or Jerome Kern, or Gershwin or Verdi, makes me wonder how much we’ve changed and what those changes may mean.

“I don’t doubt that for many young people today, the opulence of the Tibbett baritone, and its operatic connotations, are insuperable obstacles. I think of how much they’re missing.”

LISTENING GUIDE (tune in here):

00:00: “Oh Bess, Oh Where’s My Bess?”

2:42: “Wanting You”

4:18: Commentary by Thomas Hampson on “Wanting You”

6:40: “In the Still of the Night”

9:33: “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”

15:16: Commentary by John McWhorter on “singing Black”

21:02: George Shirley on Porgy and Bess

24:08: “Standin’ in the Need of Prayer” (from The Emperor Jones)

26:02: George Shirley on The Emperor Jones

30:15: “Di provenza” (from La traviata)

34:40: Jago’s Credo (from Otello)

37:35: Conrad Osborne on what makes Tibbett “American”

Wonderful piece, Joe, thank you so much! I’ve been a Tibbett fan ever since my grandmother and mother introduced me to him via their recordings. They heard him sing in concert many times, whenever he came to Detroit. And regarding John McWhorter’s comment about white people doing Black English, I couldn’t agree more. One of my earliest introductions to this was hearing the great comedian Jonathan Winters do Black characters in his routines. He completely nailed the voice, but it was done with total love and respect. Winters had served with Blacks in the Marines in WW2 and had many Black friends, but I’m afraid if he were doing such a routine today he would be lambasted for it. People need to be able to tell the difference.

Excellent article, Joe; many thanks! I’ve been a Lawrence Tibbett fan ever since I first listened to the recordings my grandmother and mother had. They both loved Tibbett and heard him many times in person when he came to Detroit. I also agree with John McWhorter about white people “dipping into Black English.” The great comedian Jonathan Winters would often do Black characters in his routines, and his dialect was dead-on. The imitations were always done with total love and respect—Winters had served in the Marines with Black soldiers in WW2 and had many Black friends in and out of show business. Unfortunately, Winters would never be able to get away with routines like those today. People need to be able to tell the difference!

Tibbett had the gift that I hear consistently in Maria Callas and Enrico Caruso and in Jon Vickers, Fritz Wunderlich, Leontyne Price, Renata Tebaldi and others in their very best recordings: an expressiveness that is more than musical. More than just singing beautiful music well, Tibbett captures the human heart of the roles and makes me believe that I am truly listening to a person in the situation he is portraying. Has anyone ever sung the final lines of Rigoletto so heartbreakingly? I agree with Joe Horowitz 100% about “Di provenza.” Tibbett sings the music from the inside out. This is why we have opera. The recordings of Tibbett are an American national treasure , on par with the works of artists like Gershwin, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and John Ford. I am so glad we have intellectual giants like Horowitz, McWhorter and Osborne promoting his work, and that the Marston set is out!

So as a genuine Tibbett fan (a picture of him adorns my bedroom wall), of course all I want to do is criticize anyone who dares discuss him. That said I take issue with John McWhorter’s commentary on the authenticity of Tibbett’s “black” accent. McWhorter evaluates Tibbett’s authenticity by the standard of speech (approvingly). But Tibbett was an opera singer and sang with the same technique no matter what he sang, and opera singing is not speech. For example, a French singer singing French does not sing “with a French accent” he sings in the French style (or doesn’t). There is a distinctive manner of singing French, but it bears no relationship to the manner of French speech, or at best a metaphorical one.