When I embarked on my novel The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York, I felt I possessed a pretty good understanding of Gustav, and none at all of Alma. Nor are the various biographical treatments of Alma adequate – she escapes portraiture, and the basis of her legendary allure remains inscrutable. My only way forward was to endeavor to experience Mahler’s glamorous spouse, and her bewilderingly new surroundings, as best I could. As I have earlier testified in this space, I learned the most when juxtaposing her with women of high professional achievement – in particular, with the Wagnerian soprano Olive Fremstad (the Callas of her time) and the young Natalie Curtis, who documented the music of Native America. In these encounters, as I re-imagined them, Alma clarified her insecurities. And of course in narrating the volatility and vulnerability of her husband (my book is not hagiography), I incidentally rendered Alma’s vicissitudes more understandable.

But it has come as a complete surprise that all reviews of The Marriage discover something like a breakthrough account of Gustav Mahler’s wife. The latest, by Kenneth Woods (a gifted Mahler conductor and scholar) in The American Purpose, reads in part:

“In a novel of so much value, the central triumph is not Horowitz’s ability to humanize Mahler, but to have provided readers—for the first time in my experience—with a nuanced, believable, balanced, and compelling portrait of Alma Mahler. Like her husband, Alma’s was a complex and contradictory personality, and this has made it easy for writers to appropriate her for their own ends.

“To some, Alma remains the villain in Mahler’s life story—the woman who broke his heart and his health, and whose writings were so full of misleading and dishonest details about the man that she damaged his posthumous reputation far more than any critic. Her antisemitism and alcoholism have not made her a particularly sympathetic figure, either. To others, she was the innocent victim of Mahler’s misogyny, a woman denied the opportunity to exist on her own terms and forced instead to be “wife and mother” to the great man, to serve the cause of his genius. Neither of these extremes is credible.

“Horowitz’s Alma is the first incarnation of her this author has encountered that actually seems like a real person. And, fittingly for a book entitled The Marriage, the novel is as much, if not more, hers as her husband’s. There are so many questions about Alma and her marriage to Mahler, and most of them begin with “Why?” This was the first book in which I felt like I was getting believable answers.”

Lower down, Woods writes of my portrayal of Mahler’s crucial New York predecessor, the conductor Anton Seidl, that his “shadow looms over the tragic events Horowitz captures so poignantly. As such, he emerges as perhaps the figure one most looks forwards to learning more about.” A protégé of Richard Wagner, in effect Wagner’s surrogate son, Seidl is in fact the central character of my next book – another historical fiction that’s a prequel to The Marriage: The Disciple: A Tale of New York in the Gilded Age.

You can read the rest of Kenneth Woods’ review here.

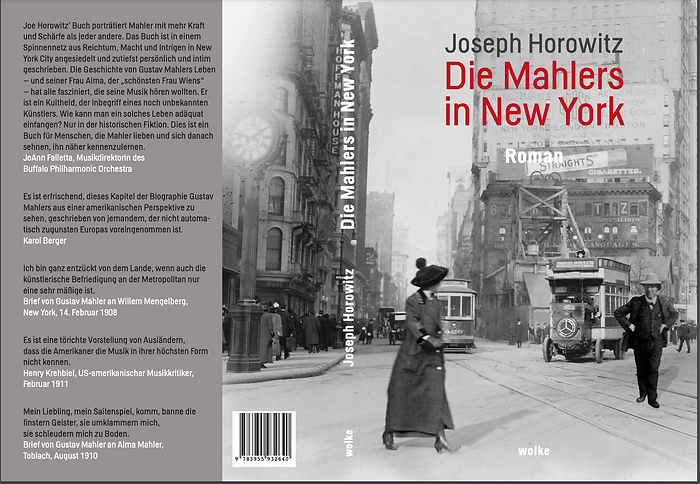

Related news: a handsome German edition of The Marriage has just been published by Wolke Verlag (the ingenious cover sits atop this blog). A Korean version is forthcoming. I will offer a talk on Mahler and Schubert (“Taverns in Paradise”) at the Colorado Mahlerfest this May 18. And Mahlerei – my bass trombone concertino adapting the Scherzo of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony for David Taylor – will receive a Mahlerfest performance three days ahead of that.

Leave a Reply