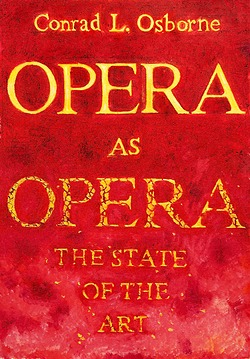

On the heels of my Tannhäuser blog, Conrad L. Osborne has posted yet another of his indispensable mega-essays – on the topic of cultivating American opera.

I wrote: “The arts are today vanishing from the American experience. There is a crisis in cultural memory. How best keep Tannhäuser alive? Flooded with neophytes, the Metropolitan Opera audience is very different from audiences just a few decades ago. What I observed at the end of Tannhäuser was an ambushed audience thrilled and surprised. The Met is cultivating newcomers with new operas that aren’t very good. A more momentous longterm strategy, it seems to me, would be to present great operas staged in a manner that reinforces – rather than challenges or critiques or refreshes – the intended marriage of words and music. For newcomers to Wagner, an updated Tannhäuser would almost certainly possess less ‘relevance’ than Otto Schenk’s 46-eyear-old staging – if relevance is to be measured in terms of sheer visceral impact.”

Conrad writes of the Met’s sudden espousal of new works: “The company’s current management has undertaken a program of artificial insemination in place of what was once natural conception—hence the ethnocultural distribution [catering to Black and Latino audiences] . . . , to which we can add a sexual identity element, as well. This is not a program of audience integration . . . , but of audience fragmentation, in perfect synchronization with the oft-remarked silo-ing of group identities in our society as a whole.”

And Conrad contrasts the current crop of new operas mounted by the Met with the New York City Opera’s more informed attempt to curate American opera back in the 1950s. Of that crop, he writes: “Several of the sturdier American operas maintained a hold in the NYCO repertory through the 1960s, along with several more 20th-Century European works, and the company’s first season in its new home at Lincoln Center (Spring, 1966) consisted wholly of post-WW1 operas, though just three of the eleven were American. The pattern did not hold, of course.”

The composers Conrad mentions whose operas enjoyed an “occasional return” at City Opera are Gian Carlo Menotti, Kurt Weill, Carlisle Floyd, Douglas Moore, Marc Blitzstein, and Robert Ward. I would add that our pre-eminent American grand opera, Porgy and Bess (1935), was also given at NYCO. My two cents: in second place I would position Blitzstein’s Regina (1948), adapting Lillian Hellman’s Broadway triumph The Little Foxes. Too many of the new and newish American operas nowadays at the Met are makeshift efforts best assigned to much smaller spaces. Regina is the real deal; suitably cast with big voices and personalities, honestly produced without special pleadings, it would flood the big house with drama and song. It adroitly sets the English language. It powerfully critiques class and race. As once with Porgy , unproduced at the Met for half a century, Regina remains — now more than ever – a beckoning, high-stakes Metropolitan Opera opportunity.

Also, this Tannhäuser afterthought: As it happens, not long after experiencing the Schenk Tannhäuser at the Met in 1977, I attended the Bayreuth premiere of Götz Friedrich’s Tannhäuser – a polemical anti-Fascist staging that became famous. My chief reaction, at the time, was that I’d never witnessed such terrific, painstakingly rehearsed acting, top to bottom, on an operatic stage. I also felt intellectually tantalized. But it is the Schenk Tannhäuser , re-encountered last Tuesday, that made me weep during the finales of acts two and three. In these days of synthetic groupthink outrage, weeping has perhaps become somewhat passé. And perhaps that’s pertinent to whatever makes Otto Schenk’s Tannhäuser seem “old-fashioned.”

***

A torrent of emails suggests that my Tannhäuser blog has struck a responsive chord — and I feel impelled to say a little more about Wagner and Regietheater. Gotz Friedrich’s Bayreuth Tannhäuser, whatever one makes of it, was self-evidently a product of intensive engagement with music and text; where he departed from Wagner’s intended marriage of notes and words, he had his reasons, good or bad. The same Bayreuth summer, I encountered the premiere of another famous production: Harry Kupfer’s The Flying Dutchman. In fact, i reviewed it for the New York Times (if you look it up, the misspellings [“Terry Kupfer,” “Hans Knattersbusch,” etc.] and misconstrued words were a result of trans-Atlantic dictation via telephone in pre-email days). Kupfer, too, knew exactly what he was doing. I was stunned by his conceit that the main action of the opera was hallucinated by the deranged Senta. I found her character fortified — and also that of Erik, who understood his beloved all too well. The trade-off was a shallower Dutchman, reduced to an idealized figment of imagination. But what most lingered was Kupfer’s ingenious delineation of twin stage-worlds coincident with twin sound-worlds. As I once wrote in this space: “Kupfer’s handling of musical content was an astounding coup. The opera’s riper, more chromatic stretches were linked to the vigorously depicted fantasy world of Senta’s mind; the squarer, more diatonic parts were framed by the dull walls of Daland’s house, which collapsed outward whenever Senta lost touch. In the big Senta-Dutchman duet, where Wagner’s stylistic lapses are particularly obvious, Kupfer achieved the same effect by alternating between Senta’s fantasy of the Dutchman and the stolid real-life suitor (not in Wagner’s libretto) that her father provided. Never before had I encountered an operatic staging in which the director’s musical literacy was as apparent or pertinent.”

What most disturbs me about Regietheater at the Met is the prevalence of directors who seem tone deaf, even musically illiterate; they steamroll the calibrated music-and-words alignment that is the lifeblood of opera, its very reason for being. Robert Lepage’s Ring is merely the most notorious example.

If you happen to listen to that 1936 Met Tannhäuser (extolled in my previous blog), begin with act three: Lawrence Tibbett (Wolfram) and Lauritz Melchior (Tannhäuser). It wil cost you an hour. Follow the libretto. I just re-experienced their interaction with my wife. She said when it was over: “Every word is emotionally articulate.” Precisely. And so is the orchestra. It is an exercise in empathy.

While I too have been enthralled and moved by the production of Tannhauser you write about (having first seen it with Johan Botha at the Met) and have a strong preference for the operas of Verdi, I think that for opera to thrive and remain a living art form, new productions and operas must be brought to the stage. While I was a classical music lover, I did not become the opera goer I am today until I went to see Dr. Atomic, an American opera, where I experienced the tension and drama that is unique to opera and that whetted my appetite for more.

To attract new audiences,, the MET should concentrate on “Grand Opera” such as Mefistofele, Turandot, Semiramide, Carmen, Tosca, etc. As a subscriber to the MET on-demand streaming service, I find that many of the older productions are far superior to the more recent ones. Just compare the older Hansel and Gretel to the newer version. Or any of the older Don Giovannis to the current production.

As a MET subscriber, this season is the weakest in 20 years.

To be another voice, my first HANSEL AND GRETEL was the old Met version and I loved it often. However, the new version crossed from being a musical fairy tale to gloriously musical art. I, too, watch MET On-Demand and this week I wallowed, again, in the new H&G with its dish-washing Dew Fairy and its incomparable Chef/Angels. THAT brought me to tears like no Flying by Foy ladies ever did. I’m grateful to the MET for its new works and new productions of old works. It keeps my 57 year-old opera habit young and fresh. BTW, my first opera was that radical Wieland Wagner LOHENGRIN of 1967 that dared violate R. Wagner;s rules. Why, why,…it was that awful Regietheater!!!! I was 16 and found it fascinating.