Conrad L. Osborne has now chimed in with a typically riveting review of the Met Tannhäuser, bristling with insights into the opera and its performance last December 12. Read it.

As a brief postscript to my three previous Tannhäuser blogs, and Conrad’s blog, would like to draw particular attention to his observations about the current condition of the Met orchestra, as revealed in the opening pages of the opera’s famous overture:

“The playing almost never sounded committed to the beauty and drama of the writing. It was generally obedient to the letter of its law, but never to its spirit. This was patently true of the strings, and—not to overlook the placidity of the lower-voiced viols—most patently of the violins. As important as the other choirs are in our mind’s-ear evocation of a Wagnerian texture, it is the strings, led on by the violins, that carry the writing forward the largest share of the time, as in most composition for a classical orchestra. So (staying with the first couple of minutes of the Overture, one of the all-time greatest) you have only to imagine the first string entrance, in the cellos, with the Burden of Sin theme (“Ach, schwer drückt mich der Sünden Last” is your textual reference); then the violins taking up the theme, but higher, with a seraphic tint that suggests that though sin still exerts its drag, a light gleams on high—both these brief, leaning-forward statements played calmly and prettily, without the slightest hint of a counterforce, of an inner struggle; and finally, over the fortissimo entrance of the brass and percussion with the Pilgrim’s Chorus, one of the score’s most famous effects, the overlay of descending violin triplets, utterly undone by a literal picking-apart of each triplet into evenly played duplets interrupted by rests, with no sense of attack or of playing through, as if the players just didn’t know how this is supposed to go.”

To add my two cents: The mechanical rendering of the violin triplets during the first grand statement of the pilgrims’ theme produced the audio equivalent of blinding strobe lights flashing at regular intervals; it was bewilderingly odd. As for the entrances of the cellos and violins a little earlier on (as described by Conrad), just about any credentialed recording of this glorious passage will convey its gravitas and ardor. Try, for instance, Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Vienna Philharmonic in 1952. It would be a simple task to notate the many inflections of pulse, tempo, and dynamics, including a characteristic climactic allargando, here interpolated by the conductor and players. But it would be impossible to replicate this performance accordingly; the urgency of the pilgrims’ song must be felt. And unless this overture strives, it cannot possibly launch the opera.

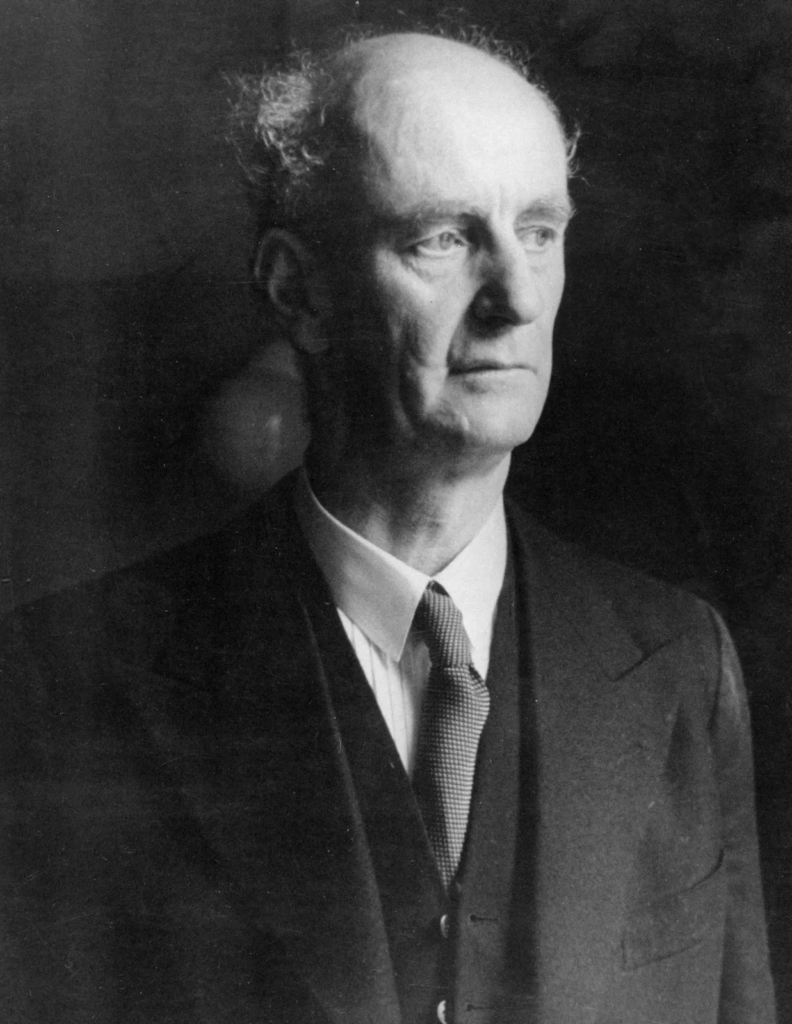

Many years ago, when the Met orchestra regularly failed to make much of Valery Gergiev, I urged one of its members to attend a New York City concert by Gergiev and his own Mariinski Orchestra. He did – and discovered the majestic soundworld that Gergiev was trying to instill in the Met pit. Though it will never happen, one thing that would improve matters in today’s Met pit would be a listening exercise. I am certain that some members of the current Met orchestra would be flabbergasted to discover to what it sounded like in the days of Artur Bodanzky and Ettore Panizza – beginning with the sheer energy of the playing. This was still an Italianate band, once led by Arturo Toscanini. It specialized in hair-trigger attacks and cantabile slides in the strings. It brought its own galvanizing style and powderkeg intensity to Wagner and Verdi, especially with Bodanzky and Panizza on the podium. Those broadcast recordings remain not only inspirational, but specifically instructive — moreso now than ever.

Leave a Reply