The upcoming Sesquicentenary of Charles Ives (1874-1954) is a landmark moment in American cultural history. Not only is he the towering creative genius of American classical music; he links to the highest American cultural pantheon, resonating in countless ways with the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Herman Melville (connections I explore in my book Dvorak’s Prophecy).

Judging from the website bachtrack, Ives is today far more performed in Europe than the US. Judging from Wikipedia, he is still mis-categorized as a “modernist.” The Sesquicentenary is an opportunity to claim Ives for his American time and place: the late Gilded Age and American fin-de-siecle.

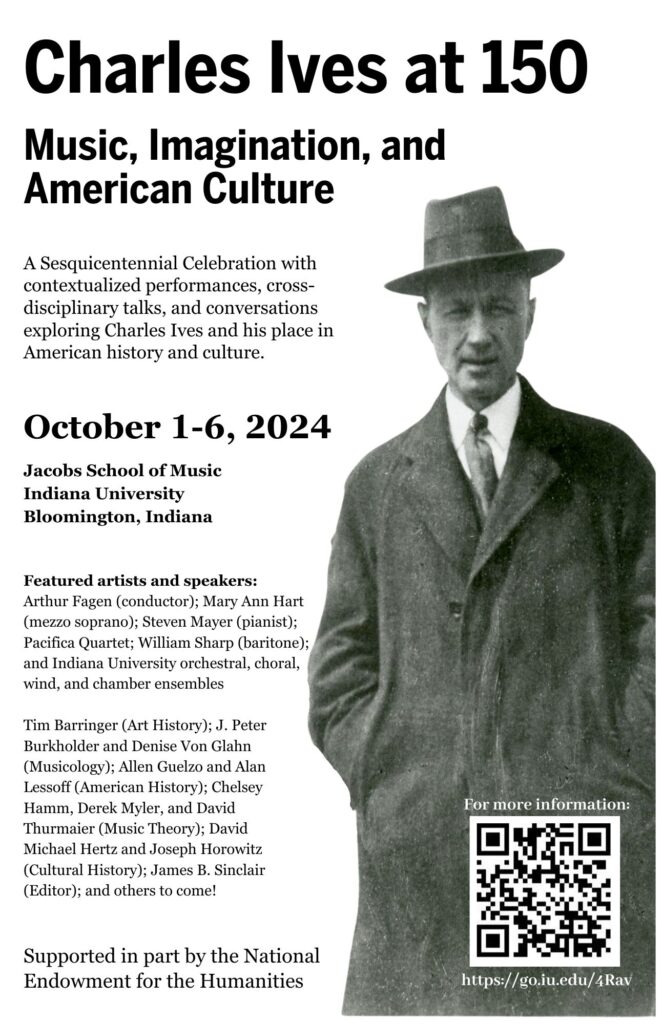

Thanks to J. Peter Burkholder, the central celebration will take place at Indiana University/Bloomington, where the Jacobs School of Music is planning a week (October 1 to 6, 2024) of contextualized concerts, cross-disciplinary lectures, and discussions supported by the NEH Music Unwound project that I direct. There will also be NEH-supported Music Unwound Ives festivals at the Brevard Music Center (mid-July, 2024), Bard College (including a Carnegie Hall concert by Bard’s The OrchestraNow – November, 2024), and Chicago (the Chicago Sinfonietta in collaboration with the Rembrandt Chamber Players and Illinois State University/Normal — mid-February, 2025).

The Bloomington festival is notable for the participation of scholars outside Music. These include a major art historian specializing in the 19th century “American Sublime” (Tim Barringer), a major Civil War historian who really knows music (Allen Guelzo), a major Gilded Age historian who can track the etymology of that troubled label (Alan Lessoff). My own contribution will juxtapose Ives with Mahler (who similarly oscillates between the quotidian and the sublime), and with Sibelius and Elgar (who similarly stopped composing, vexed by modernism and modernity, rooted in native landscapes). I already know that I will say:

“Among canonized composers of classical music, Charles Ives possesses the most elusive, least stable reputation; he remains a moving target. That at the same time he is for many the supreme American creative genius among concert composers, a figure protean and iconic, must say something about America and Ives both: as ever, we’re not sure who we are. Even our orchestras and instrumentalists perform him far less than they should.

“Ives’ first reputation, congealing midway through the twentieth century, was framed by modernists who pedigreed ‘originality.’ Ives’ ‘experiments’ in tonality and rhythm were compared with those of Arnold Schoenberg – whose music he did not know. This obsession with ‘who got there first?’ pigeonholed Ives as an intriguing historical anomaly rather than an expressive genius. It placed him firmly in play, but proved essentially patronizing.

“Once the modernist criterion of originality dissipated, it became possible to resituate Ives not as an anomalous victim of repressive materialistic decades, but as a complex product of a dynamic period of American growth itself undergoing revision. Hence the sesquicentenary opportunity at hand, celebrating the 150th birthday of this most volatile cultural bellwether.”

What a fabulous celebration. Thank you so much for organizing this. Best wishes for a great success!