Writers discover quickly that their books – any books – have no fixed meanings. They will read differently to different readers. And their printed words never precisely convey an author’s thoughts and stories.

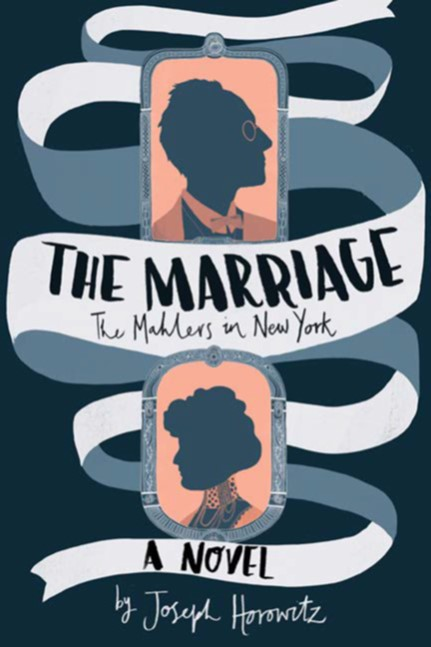

Processing the response to my first novel – The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York – I now further discover that fictionalized characters and events all the more elude authorial control.

My good friend Bill McGlaughlin (esteemed conductor/inimitable broadcaster) writes to me of Henry Krehbiel – alongside Gustav and Alma, one of the three main characters in my historical fiction: “Has there ever been a bigger blowhard, stuffed fat with his own self-importance?”

I wrote back: “Bill, I LIKE Krehbiel.”

Bill: “I know that!”

Bill also writes: “For the first time in my experience, Alma Schindler/Mahler/Gropius/Werfel emerged not as a stick figure in the margins of the story, but central . . . As I read I became increasingly fond of her and sympathetic in a way that was new to me.”

Similarly: Peter Davison, in a review just posted, writes: “The most striking insights of The Marriage are about Alma.”

And yet I did not purposely undertake a newly compassionate portrait of Alma.

What I absorb from these responses (both of which begot further responses via email) is that Henry Krehbiel, in my book, stands on his own two feet, as does Alma Mahler on hers. Davison added: “Readers will respond according to their own feelings . . . because you are not steering them towards any particular judgments.”

Anyone familiar with my previous eleven books – anyone familiar with me, period — will appreciate that all my life I have been steering people towards particular judgments. And I now discover within myself novelist who does not do that. I marvel at this wholly unconscious transformation.

I share more of what Peter and Bill wrote below.

From Peter Davison’s review:

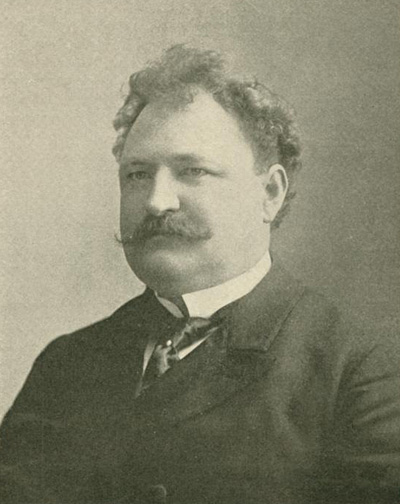

We are offered by the author a portrait of Mahler that is real. . . .

The most striking insights of The Marriage are about Alma. . . . The book lays bare the paradoxes of Mahler’s character which Alma had patiently to endure. His hypersensitivity and infantile insecurities co-existed with a tyrannical willpower which spared no one – particularly not Alma, least of all himself.

We see how Alma was at one level willingly compliant with Mahler’s demands. She needed to be needed, to be lover, mother and nurse, as well as mid-wife to the products of genius. And Alma [herself] was a bundle of contradictions, more unsure of herself in New York society than might have been expected, particularly when faced with independent-minded women . . .

In conclusion, I should draw attention to Horowitz’s use of language . . . Most impressive are his poetical accounts of Mahler’s music which profoundly acknowledge the composer’s genius, signaling that the author has no wish to diminish Mahler’s musical achievements. Descriptions of rehearsals for the Fourth Symphony in New York and the triumphant premiere of the Eighth in Munich stand out, capturing in just a few words the spirit of these great, if vastly different, works.

The Marriage is a brave experiment, following wherever the imagination leads to fill gaps in historical knowledge and to test the validity of long held assumptions.

From Bill McGlaughlin:

For the first time in my experience, Alma Schindler/Mahler/Gropius/Werfel emerged not as a stick figure in the margins of the story, but central. Wayward, mercurial, fascinating, devoted to her husband and yet living (and concealing) her own life. As I read I became increasingly fond of her and sympathetic in a way that was new to me. . . .

Going deeper and deeper, below his scholarship, Joe really imagines this lost world in a way we can enter it with him. This is his greatest achievement, I think. . . .

Along the way Joe lets us meet Mahler and his supporters and detractors, some of whom are portrayed sympathetically. Others — Henry Krehbiel, notably — are damned with their own words. (Has there ever been a bigger blowhard, stuffed fat with his own self-importance, smashing through the thickets of the music business?) . . .

To balance Krehbiel, let me cite Mahler’s insight on the real worth of Richard Strauss:

“Somewhere beneath Strauss’ insane nonchalance dwells the voice of the Earth Spirit.”

Exactly so and very generous in appraising the work of a very irritating rival. . . .

The overall trajectory of Mahler’s life in these years could leave a reader despondent. Then, just when we’re about to abandon all hope, Joe gives us the story of the premiere of the Eighth Symphony in Munich, one of the greatest triumphs of Mahler’s life. This chapter is filled with love and music and children and leaves us with the will to go on.

Joe’s Mahler & Alma is a staggering achievement, enthralling, moving and inspiring. Reading its final pages, with Busoni appearing as an Angel of Death, one has the sense of having completed a profound journey, although one that is only a prelude of what is to come in the years beyond. Mahler is now heard around the world. And this book deepens our experience and satisfaction and love.

So look forward to getting my hands on the book!