In recent weeks I’ve had occasion to perform Harry Burleigh’s “Lovely Dark and Lonely One” with three singers: Emery Stephens at St. Olaf’s College, George Shirley for Chamber Music Cincinnati, and Sidney Outlaw at Princeton University. And I write in this weekend’s Wall Street Journal that this “may be credibly judged one of the most memorable of all American concer songs.’” In fact, I argue, it may be understood as Burleigh’s 1935 valeictory, a song (setting but re-interpreting Langston Hughes) about Burleigh himself, preaching faith and forbearance. The recordings I have encountered of this song seem a little small to me; I hope to be able to post the Cincinnati or Princeton performance in the coming weeks. That said, you can listen to a lovely reading here.

I write in part:

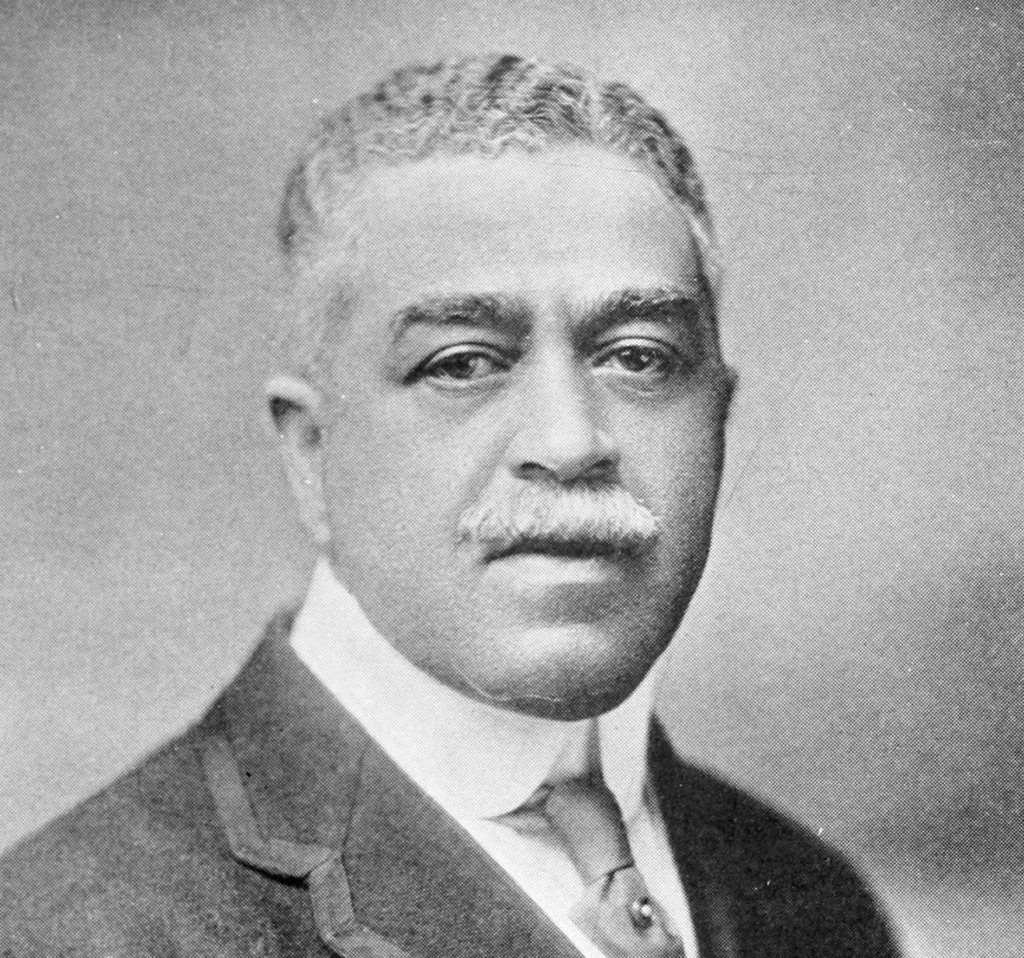

Burleigh (1866-1949) is the pivotal figure in the transformation of the spirituals of the American South into solo concert songs. You might even say that black classical music begins with the five versions of “Deep River,” for solo voice or chorus, that Burleigh created between 1913 and 1917. Their impact was electrifying. . . . He [also] became a prolific composer of art songs distinct from his arrangements of spirituals. This body of music was exceptionally popular into the 1920s, championed by John McCormack . . . and other prominent recitalists of the day. Burleigh’s spirituals are still widely sung. But beginning in the late 1920s, his art songs swiftly receded from view. In the context of modernism, of the Harlem Renaissance and its enthusiasm for jazz, Burleigh sounded old-fashioned. . . .

Re-encountered today, this late song seems a valedictory. Only two minutes long, it is—even for Burleigh—a superb exercise in concentration: of mood and expression, of melody, of mobile harmonic activity. It achieves a compositional voice as personal as his spiritual arrangements are elemental. The piano part, virtually symphonic, is co-equal with the voice, with which it eloquently interacts. The mediation between black (bluesy harmonies) and white celebrates the duality of Burleigh the man and artist. Nowhere is Burleigh closer to Wagner; he virtually quotes the Prelude to Tristan und Isolde—an opera he attended 66 times at the Met. But the most distinguishing feature of this exceptional song is that Burleigh has re-interpreted Hughes’s poem . . .

Processing Hughes’s expression of impatience, Burleigh turns the poem upside down. His method is to first score the closing word, “wait,” as an exclamation crowning the vocal line—and then to twice reconsider it, softening and caressing it so that the meaning turns serene: an expression of forbearance and faith. He then reprises the poem’s first two lines . . . so that the final quiet melodic ascent consecrates youth and sunlight. In this 12-bar sequence, it is the intervening piano that becalms the singer, claiming a lasting philosophic repose. Not for Burleigh is Langston Hughes’s agitation, or the activism of a Paul Robeson. Nor is there the merest hint of modernist dissonance. We do not have to agree with him in order to admire the eloquence with which he here sustains his credo . . . that “deliverance from all that hinders and oppresses the soul will come and man—every man—will be free.”

Burleigh intended “Lovely Dark and Lonely One” for Marian Anderson, whom he mentored, and whose renditions of Burleigh’s “Deep River” were indelibly her own. But Anderson chose not to sing “Lovely Dark and Lonely One.” It is in fact a song personal to Harry Burleigh. It also happens to be Burleigh’s final concert song. If he therefore quit composing art songs at the peak of his creative powers, his truncated odyssey bears comparison to other, more famous casualties of modernism: Charles Ives, Edward Elgar, Manuel de Falla and Jean Sibelius, all of whom stopped composing when they discovered themselves aesthetically estranged after World War I. . . .

Leave a Reply