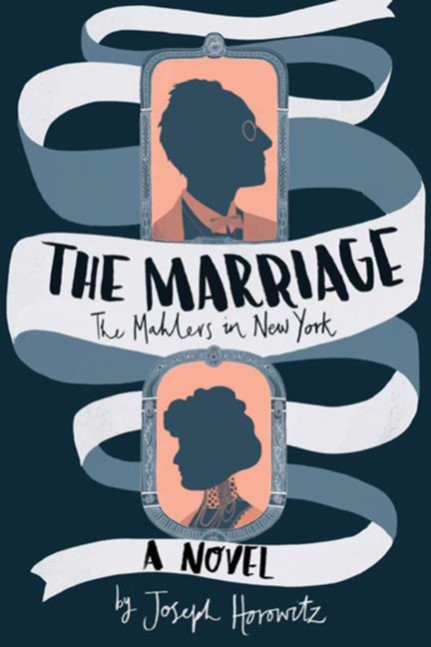

“How would you compare Mahler and Toscanini in New York?” asked Kenneth Woods, Artistic Director of Boulder’s Colorado MahlerFest, in a zoom conversation a few days ago about my new novel: The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York (the official pub date is this Saturday).

You can see and hear my answer here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wXCgIWXRoqk

You can also hear me in conversation with Morten Solvik of the Mahler Foundation on “The Mahler Hour” this coming Saturday at 10 am ET by tuning in here: https://www.youtube.com/c/MahlerFoundation

If you want to know what I said about Mahler and Toscanini without bothering with the link, I said this:

Mahler was displaced at the Metropolitan Opera by “an Italian juggernaut.” “Mahler didn’t care to investigate the New York musical situation he encountered in 1907. This got him into a lot of trouble and signifies, I would say, his most striking personal trait – that he lived inside his head. And that’s fine if you’re a composer. It’s not so great if you’re a music director.”

As for Toscanini – “Unlike Mahler, you couldn’t oppose him. If Mahler was opposed he’d get upset. If Toscanini was opposed, he would just bulldoze over every adversary. And when he decided that he was going to appropriate the Wagner repertoire, Mahler fought a completely futile rearguard action before realizing that he was outgunned. Being rebuffed at the Met, he would up conducting the New York Philharmonic. . . Imagine these dueling personalities in New York, Mahler and Toscanini – that itself could be a book, but it’s never been written.”

Kenneth Woods: “Maybe that’s your own next book.’

JH: “I think I shot my wad in Understanding Toscanini in 1987. Whenever I return to that topic, there are still people around who get very upset,”

When asked to summarize my new novel (5:30), I reply: “It was a very taxing moment for this very odd couple. It’s an interesting context in which to observe Mahler and his wife – as newcomers.”

KW: “Who thrived more?”

JH: “That’s a mind-boggling question.” For Mahler (as for Toscanini, after World War I), New York signified among other things an opportunity to conduct symphonies – something he couldn’t much do in Europe. As for Alma: “Things are here even more complicated. She’s much harder to read than her husband because she’s someone in a state of internal confusion about who she is and what she wants. Did New York clarify this for her? I don’t think so. I would say this: at least for me, her most revealing moments are when she finds herself in the presence of a woman more professionaly accomplished than herself. You know, you learn things when you write historical fiction.” In my book, in the presence of the soprano Olive Fremstad, and of the fledgling ethnomusicologist Natalie Curtis, Alma “realizes what she wasn’t.”

KW (at 10:17): “In writing a historical novel, where are the borders between fact and fiction?”

I here distinguished between “historical fiction” and “creative non-fiction.” I add: “My book is two things – it’s a novel and it’s also the first book-length treatment of the Mahlers in America – a topic that’s been murdered because everybody who writes about it knows next to nothing about New York.” Mahler’s New York “was a world music capital” in which Anton Seidl and Antonin Dvorak, dominant in the 1880s and 1890s, cast long shadows. And there was Mahler’s nemesis, the critic Henry Krehbiel, who quite accurately declared Mahler’s New York tenure “a failure.” An initial crisis (13:35): When, as the Philharmonic program annotator, Krehbiel asked permission to print Mahler’s program for his First Symphony, he wound up writing a program note disclosing that Mahler forbade program notes. “Their relationship deteriorated after that.”

KW (at 15:20): Did the ‘factionalized” music critics in Vienna influence Mahler’s standoffish behavior towards Krehbiel and other New York critics?

JH: “American music criticism is a species unto itself – especially in this period, when it’s at its apex.” Krehbiel and others filed their reviews immediately — they appeared the next morning. This practice was unknown abroad. Also: “As Mahler may or may not have noticed, there was no anti-Semitism in the New York musical press.”

To close on a note of controversy (18:40), I opine that those Viennese critics who called Mahler’s music, and even his interpretations, “Jewish” were “not necessarily anti-Semitic.” I here reference Arthur Farwell’s remarkable blow-by-blow review of Mahler’s Mahleresque reading of Schubert’s Ninth Symphony with the Philharmonic, in the Musical America — a crucial text for my treatment of Mahler in performance in The Marriage..

–I speak at the Boulder’s Colorado MahlerFest symposium on May 20.

–My “Mahlerei” for bass trombone and chamber ensemble will be performed at the Brevard Music Festival on July 5 (with sui generis soloist David Taylor).

–My “Einsamkeit,” re-imagining songs by Maher and Schubert (also with David Taylor), will be performed at New York City’s Peridance Center on June 17 and 18, with choreography by Igal Perry.

My best experience of Mahler was hearing his re-orchestration of the Beethoven symphonies. Using the larger orchestra and instruments available in the 20th century, Mahler’s Beethoven’s symphonies sounded better than the originals.

First off, I know conductor Kenneth Woods for his wonderfully cogent commentary about

Eugene Ormandy (viewable on Wikipedia article about same). That, plus the quality of the

dialogue between him and Joe Horowitz, is enough reason to read and reread the above

piece. Mahler, well, maybe it’ll eventually come — for me, Symphonies such as 6 and 8 are

so unwieldy and turgid (with all those Wagner-like claims of Gesamkunstwerk ) that, well,

they, structurally and semantically, don’t hang together well. JH’s analysis though of

anti-Semitic bias toward Gustav Mahler (0r the lack of it) with both NY press and Viennese

critics will have me returning to this article. And seeking out more books on the subject.

Dr. Joseph A. DiLuzio, Ph.D.

Quick follow-up: friends, music critics and members of the Philadelphia Orchestra

argue with me concerning my antipathy for much of Mahler (too much!, I’d say, punning,

in our own concert hall). Let’s put it this way: why do Bruckner and Shostakovich

really hit home with some of us, while GM, despite the imagination and often

overwhelming sonic splendor of the music tries our patience?! It’s a fair question.

Mahlerites need not worry. Like it or not, he’s the most played symphonist after

Beethoven.. The latter’s genius, whether via piano, orchestra or string quartet

continue to comfort and boggle the mind of this listener.

Dr. Joseph A. DiLuzio, Ph.D.