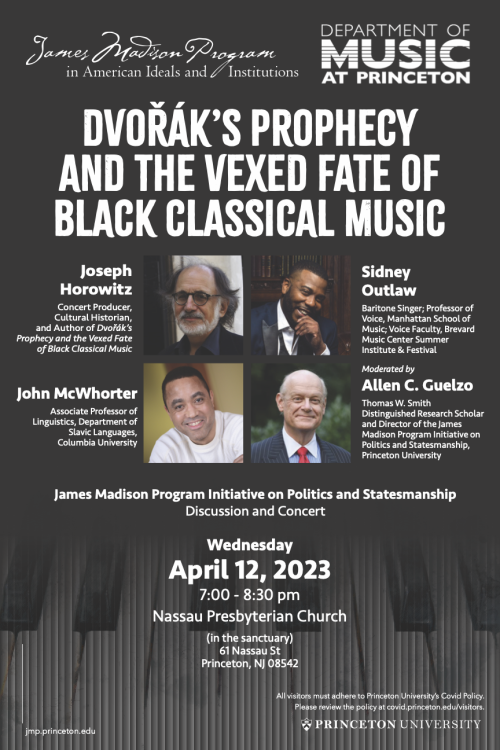

“Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music” is the topic of an April 12 concert/lecture at Princeton University. I’ll be joined by cultural critic John McWhorter of the New York Times, Princeton historian Allen Guelzo, and baritone Sidney Outlaw – with whom I’ll perform spirituals and songs by Harry Burleigh. It’s free of charge and you don’t have to register. The venue is Nassau Presbyterian Church. The presenters are the Department of Music and the James Madison Program. We start at 7 pm.

McWhorter – who knows music and is a regular contributor to my “More than Music” programs on NPR – will address the significance of George Gershwin and the place of Black classical music. Guelzo – who knows music and is an occasional contributor to “More than Music” – will address the significance of Charles Ives, both with reference to the Civil War and the American cultural pantheon generally. Outlaw – a magnificent concert singer with roots in the Black church – will address African-American vocal composers now being rediscovered.

A special focus of attention will be Harry Burleigh’s “Lovely Dark and Lonely One” (1935), setting Langston Hughes. it’s one of the most memorable concert songs ever composed by an American. Turning Hughes’ poem upside down, it counsels faith and forebearance. Burleigh’s valedictory, it places him in a lineage with Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson, both of whom he mentored.

I will also have a piece on Burleigh in the April 1 Wall Street Journal, in which I write:

“Burleigh intended ‘Lovely Dark and Lonely One’ for Marian Anderson, whose renditions of Burleigh’s ‘Deep River’were indelibly her own. But Anderson chose not to sing ‘Lovely Dark and Lonely One.’ It is in fact a song personal to Harry Burleigh. It also happens to be Burleigh’s final concert song. If he therefore quit at the peak of his creative powers, his truncated odyssey bears comparison to other, more famous casualties of modernism: Charles Ives, Edward Elgar, Manuel de Falla, and Jean Sibelius, all of whom stopped composing when they discovered themselves aesthetically estranged after World War I.”

Leave a Reply