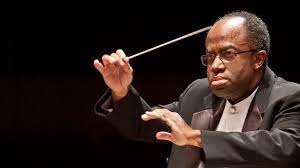

The death of Michael Morgan, last August 20, was a heartbreaking loss to American music. As music director of the Oakland Symphony since 1991, he was a singularly impactful conductor.

The evidence, as I discovered Friday night at an Oakland Symphony concert that in many respects invoked his memory, is a symphonic audience unique in my experience. “Diversity” is a term so over-used today as to lose all meaning. The dictionary says: “including or involving people from a range of difference social and ethnic backgrounds.” So variegated is the Oakland Symphony audience – in age, ethnicity, attire, and attitude – that it resists generalization. The resulting ambience, in the impeccably restored downtown Paramount Theatre, was casual, alert, appreciative, demonstrative. The downtown itself is funky, surprising, quiet, and beautiful – and devastated, economically, by the pandemic.

The program at Friday’s subscription concert was worthy of the audience at hand. The main offering was William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony – music I have extolled in this space and in Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music. Triumphantly premiered by Leopold Stokowski in 1934 and subsequently forgotten, this 35-minute symphony is the real deal. It is certainly one of the most formidable ever composed by an American. As I’ve written: “If the symphony’s governing mold is European, Dawson retains proximity to the vernacular: he seizes the humor, pathos, and tragedy of the sorrow songs with an oracular vehemence.”

The conductor of the Oakland performance was Andrew Grams – new to me, and also new to the Dawson. The Negro Folk Symphony is easy for audiences – its emotional fortitude and depth register unmistakably. But it’s hard for orchestras. The textures are thick with incident. The trajectory is not straightforward but pliable, eventfully plotted. The rhythms are sharp, physical, lightning quick. Grams’ careful rehearsals resulted in a go-for-broke reading. The symphony’s most striking, most original moment – the second movement coda, with its threefold seismic throb of chimes and timpani – was bravely distended, even slower than on Leopold Stokowski’s wonderful 1963 recording. The impact stunned the eager audience.

Last summer I heard an equally memorable performance of the Dawson, quicker and more brilliant, led by Mei-Ann Chen at Houston’s Texas Music Festival. I see that the Philadelphia Orchestra, which gave the 1934 premiere (also with Stokowski), is at long last returning to the Negro Folk Symphony on February 2 and 3 under Yannick Nezet-Seguin. Performances will surely proliferate in seasons to come. We should quickly approach a moment when it will become possible to compare different understandings of Dawson’s complexly poised “portrait of a race.” Also: for young American composers aspiring to fuse the Black vernacular with concert genres, Dawson’s score could become a textbook. My Dvorak’s Prophecy mantra is: use the past. That’s how lasting results are obtained.

The first half of the Oakland program featured Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody for piano and orchestra – terrifically ignited by Sarah Davis Buechner. Like Dawson’s symphony, which feeds on spirituals, this jazzy confection fulfills the prophecies of Dvorak and W. E. B. Du Bois that “Negro melodies” would foster a vital and original American classical music.

During the Harlem Renaissance, however, Langston Hughes and Nora Zeale Hurston expressed misgivings about the prospect of a Black classical music. They worried that turning the African-American motherlode into symphonies and operas could prove “sanitizing,” “whitening.” The Oakland concert began with selections from Florence Price’s Folksongs in Counterpoint for string quartet, revisited by a string orchestra. Price’s polyphonic elaboration of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” is the kind of Black classical music that recalls the apprehensions of Hughes and Hurston. It was my pleasure, in Oakland, to undertake a series of presentations in middle and high schools – schools musically enriched by a series of initiatives undertaken by the Oakland Symphony under Michael Morgan. I was partnered by a wonderful African-American soprano, Shawnette Sulker. Our program included Harry Burleigh’s arrangement for voice and piano of “Swing Low.” For Sulker, this and other historic Burleigh spirituals created opportunities for a selfless expression of sorrow and exaltation. They do not register as “sanitized.”

I am sure some will find my reservations about Florence Price gratuitous. Without a doubt, she is an important part of the story of American music. As I urge in Dvorak’s Prophecy, this is a story that impatiently awaits a genuine curatorial initiative by our major orchestras. The symphonies of John Knowles Paine, likewise, are an essential component of a narrative we need to know. They are not “masterworks.” But they lead, indispensably, to George Chadwick (whose witty symphonic scherzos already “sound American”), thence to the symphonies of Charles Ives and William Levi Dawson, in which native variants of a European genre discover fruition.

Daniel Weiss, in his up-to-date meditation Why the Museum Matters, documents the movement toward thematic exhibits some half a century ago – explorations necessarily infused with “new scholarship and didactic materials.” In the 1990s, I was the lucky beneficiary of Harvey Lichtenstein’s state-of-the-art Brooklyn Academy of Music, where innovation was a ceaseless priority. Curating “The Russian Stravinsky” for the Brooklyn Philharmonic, I engaged Moscow’s Pokrovsky Folk Ensemble, the late Stravinsky scholar Richard Taruskin, the art historians John Bowlt and Elizabeth Valkenier, the ethnomusicologists Dmitri Pokrovsky and Theodore Levin, and the conductors Dennis Russell Davies and Lukas Foss. There were two symphonic programs and a six-hour cross-disciplinary “Interplay.” Brutal folk rituals and pungent concert works were directly juxtaposed. The talks and discussions were heated, informed, and productive. The essays within the copiously illustrated program companion totalled 38 pages. The principal funder was the National Endowment for the Humanities. In short: it was, all of it, what museums do. This is the type of curatorial initiative that Black classical music deserves – and that Florence Price deserves, alongside Burleigh, Gershwin, and Dawson, among many others. There is a story here as yet unglimpsed.

As I have previously reported, George Shirley has precisely observed of Dawson’s symphony that it is a work that surprises at every turn – and that every surprise “sounds right.” Put another way: Dawson’s compositional skill and originality enable him to sustain an illusion of improvisation. And I would say the same of Gershwin. It is crucial.

But I digress. My memories of Friday’s concert are all of Gershwin and Dawson, and of an enthralling and empowering ambience inculcated over three decades by a musical leader who was equally a community leader. The Oakland Symphony has experienced a great loss. It faces a great challenge. Thanks to Michael Morgan, that challenge is at the same time ripe with opportunity.

Leave a Reply