Fill in the blanks:

“This was performed and broadcast to millions of people. And something that should resonate with all of us today is the confluence of fine art and popular art and a mass medium – something we’ve lost in this era, when we’re being sliced into ever narrower shards of demographics. The brilliance of what xxx and xxx did was to embrace all of us, in the best [Walt] Whitman spirit. To make all of us one nation, one community. How I wish we had something like that today.”

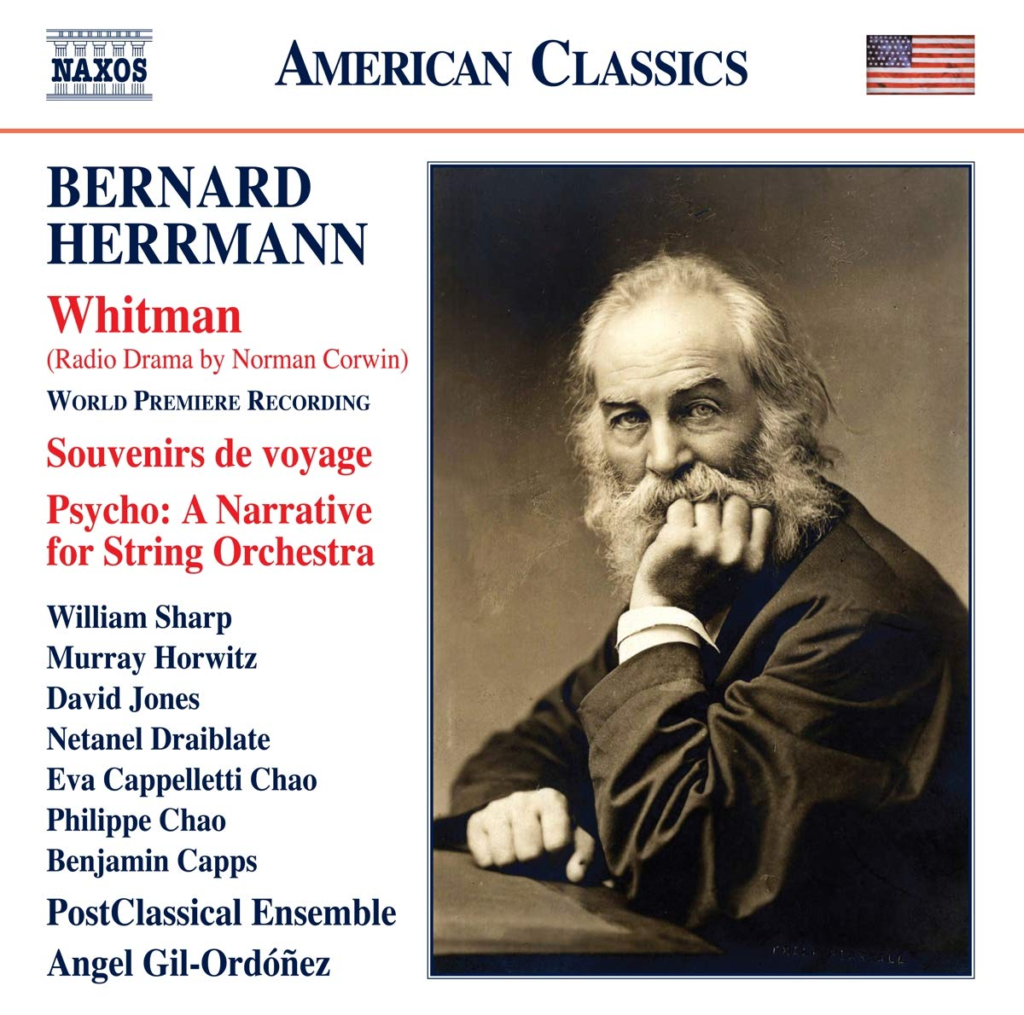

The blanks read “Bernard Herrmann” and “Norman Corwin.” The speaker is Murray Horwitz, former head of cultural programing for National Public Radio. And the source is my latest “More than Music” NPR documentary, broadcast yesterday. Its topic: the radio plays of the 1930s and 1940s generally, and the Corwin/Herrmann “Whitman” (June 20, 1944) specifically.

To hear yesterday’s 50-minute show, click here.

Following Murray’s lead, I chime in to suggest that “Whitman” (starring Charles Laughton, music by Herrmann, scripted and produced by Corwin) was “an act of democratic faith in a democratic American audience,” achieving “a kind of optimum engagement, reaching the largest possible audience without diluting Whitman’s verse. We’re very far from that ideal in today’s world of social media.”

Here again is Murray, from the same show: “Radio was IT – the only broadcast medium. And there were only four national networks. So pretty much everybody in the country was listening to the same stuff.” And the stuff was a product of live commercial broadcasting, often presented non-commercially without ads.

The further pertinence of “Whitman” is inescapable. He espoused inclusive American ideals. He healed the ripped national fabric after the Civil War.

Does the Herrmann/Corwin “Whitman” matter today? In effect, it’s a 30-minute composition for narrator and orchestra, awaiting attention. The baritone William Sharp, who takes the part of Whitman in the PostClassical Ensemble “Whitman” recording on Naxos, says: “It speaks to us so strongly,” a “magically wonderful thing” to hear were orchestras to program it.

(Herrmann is part of the “new paradigm” – the new narrative for American classical music – that I propose in my book Dvorak’s Prophecy. I continue to regard him as the most under-rated 20th century American composer. Why aren’t our orchestras programing his Moby Dick cantata? It’s certainly not because Herrmann doesn’t sell. We’re talking about the composer of Psycho, Vertigo, and Citizen Kane.)

The participants in yesterday’s radio show, in addition to Murray and Bill, include Alex Ross of The New Yorker (a huge Herrmann fan) and the Whitman scholar Karen Karbenier.

The next “More than Music” NPR documentary will air July 4. The topic (tracking Mark Clague’s superb new book) is the unlikely history of the “The Star-Spangled Banner” – which we’ll hear performed by Jimi Hendrix, Whitney Houston, and Jose Feliciano, among others. And we’ll sample verses you’ve never heard before.

Again, my thanks to Rupert Allman and Jenn White of WAMU’s “1A” for believing in what Rupert calls “long-form radio.”

A “listener’s guide” follows:

00:00 – We start with the shower scene from Psycho, “to get everyone’s attention.”

2:30 – Orson Welles and the birth of radio drama: “The War of the Worlds”

8:07 – Bernard Herrmann hypnotically sets Whitman’s paean to the grass — “handkerchief of the lord” – consecrating the young Civil War dead.

12:30 – Herrmann’s unforgettable invocation of “America the Beautiful,” a “teeming nation of nations.”

15:50 – Whitman and Herrmann extol a great democratic citizenry, “immense in passion, pulse, and power.”

19:57 – Murray Horwitz: “Radio was IT.”

21:12 – Radio’s biggest star: FDR. The first “fireside chat.”

24:29 – Whitman’s “radical vision of democracy” explored by Whitman scholar Karen Karbinier (“He strikes a perfect balance between individuality and community”).

31:29 – Dorothy Herrmann describes her notoriously irascible father reacting to a prelminary screening of Psycho (“Did you ever see such a piece of crap?”).

32:54 – Herrmann’s sublime Clarinet Quintet, featuring clarinetist David Jones.

39:04 – Alex Ross on Herrmann (“one of the most original composers of any century,” “a very great talent, one that we’re still very far from appreciating and celebrating in full.”

To purchase a related Bernard Herrmann DVD (“Beyond ‘Psycho’”), click here.

This sort of public radio is still a mainstay of European society. Similar story with television. There is a universal consensus across Europe that the people have a vested interest in a strong and widely consumed public media presence that operates independent of the marketplace.

So why doesn’t this happen in the USA? One reason we all know is that the USA practices a form of unmitigated capitalism that exists in no other developed country. This largely precludes non-profit public media.

Another reason is that public media requires a generalized social consensus that does not exist in the USA. Our political world is so far to the right in comparison to all other developed countries, that a vector is created that punctures any possible envelop of consensus. This extreme necessitates a fragmentation of society. Our market-based media then further exacerbates this problem by catering to these fragmented audiences.

A third reason, and this one is the most provocative, is that the United States is not united because it is about nine countries artificially joined by a common political system that is forced upon them. The US census map uncannily shows these nine regions. See the map at this url. Note that the heavy black borders also note regional divisions to create a total of nine:

https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

We would need about nine different public media companies, if they were to be based on a consensus general enough to allow their existence. Allowing for a certain amount of autonomy in individual local stations is not enough.

One of the reasons the USA cannot fully realize the natural cultural divisions of the country relates back to the idea that our political center is too far to the right. If regions such as the Old South and Texas, or much of the Mountain West except New Mexico, had been given more regional political, economic, and cultural autonomy, they would today be regimes similar to apartheid South Africa. A radical sounding statement, I know, but I think history shows that is a reasonable assumption.

In the end, we see that Whitman didn’t understand America. He was devoted to the truth, but like all of us, he didn’t always fully understand it. He had little to say about racism, for example, or about black America and Native Americans. He saw vividly the divisions of the Civil War, but didn’t understand that those divisions would never be fully bridged and the cultural divides they would create. He spoke of the American as a new kind of man (and woman we would add,) and didn’t see that we would end up as about nine different kinds of American men and women. Without an adequately general national consensus, America will never have a successful national public broadcaster. It could at best only be a federation of autonomous public broadcasters. Until then, we won’t have public media that as a rule will be able to create the cultural depths about which you speak. (Sorry for the long post. I know it’s inappropriate, but given your thought and writings, I think these cultural divisions are something you might effectively address at some point–part of understanding the larger cultural fabric of the USA which seems to interest you.)