At the conclusion of the National Public Radio feature I’ve produced about “The Fate of Black Classical Music,” Jenn White – who so graciously hosts the daily newsmagazine “1A” – asks me:

“In the Foreword to your new book Dvorak’s Prophecy, George Shirley – the first Black tenor to sing leading roles at the Met — writes: ‘Because of our current conversation about race, we now observe a seemingly desperate effort to make up for lost time, to present Black faces in the concert hall. But if it’s going to become a permanent new way of thinking, there has to be new understanding.’ What does he mean by that?”

I answer:

“George Shirley is 87 years old — he’s seen a lot. And as we’ve heard him say, he’s witnessed steps forward in race relations in America, and backward steps coming after those. When he talks about ‘a permanent new way of thinking,’ he means permanent change — not ephemeral change, as we’ve seen in the past. And he’s referencing what I call a ‘usable past’ – lasting cultural roots.

“You know, I went to a prestigious liberal arts college [it was Swarthmore]. I graduated a long time ago, in 1970. I majored in History. And in my four years there I never once heard the name W. E. B. Du Bois. And I certainly did not read Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, which today I regard as pretty much obligatory reading for educated Americans. Du Bois, his book – they’re part of a usable American past, something we can all utilize as an anchor.

“George Shirley references ‘a seemingly desperate effort.’ What is this about? It says that we have to rethink the concert experience in our concert halls, on our campuses. We need to rethink the learning the experience. It’s not enough just to perform Black classical music. We should use the story of Du Bois, the story of Dvorak, the story of Harry Burleigh. We need to tell stories about the American past in order to anchor a constructive American future.”

It’s my good fortune to be creating 50-minute radio documentaries for Rupert Allman, the producer of “1A.” Rupert welcomes “deep dives” into timely topics. In the case of “The Fate of Black Classical Music” (which aired on Thanksgiving), the big picture – as in my book – has to do with prioritizing something in ever shorter supply in our United States: informed historical memory. A good chunk of our show is dedicated to an exchange with the historian Allen Guelzo, whose recent biography of Robert E. Lee is an exemplary instance of “using the past” with integrity and informed understanding. Guelzo is also the rare American historian who really knows the arts, including classical music. I asked him why American historians have failed to document Black classical music. He answered:

“Historians who write about music history are usually to be found in conservatories or in Music departments. But they’re not usually found in History departments. Now perhaps the reason for that is that the people who populate History departments simply don’t see the arts as part of their turf . . . And there is a certain professional segregation that goes on that way — which suggests, however faintly and however politely, that culture is not really a fit topic of interest for historians.”

Guelzo observes that “we don’t educate people in music the way we once did.” No Child Left Behind and STEM, he continues, “have been death for arts education, especially in music. . . . Nothing surprised me more in writing Robert E. Lee – A Life than tripping over the odd fact that when Lee was Superintendent of West Point, the faculty got together to play Schumann and Mendelssohn string quartets.”

A prominent recent history of the US – Jill Lepore’s wonderfully readable These Truths – delves deeply into issues that matter today, including slavery and race. But there isn’t a single sentence on the arts. I asked Guelzo what he made of that. He replied:

“Part of it is the way historians are trained these days, in their graduate programs, which generally pay next to no attention to the arts. That was certainly my experience at the University of Pennsylvania. . . . Are we really adequately describing the lives that Americans have lived? . . . I think not. We’ve desperately shortchanged our understanding of the past.”

Guelzo calls classical music a “foreign country” for those who write about the US. “If any thought is given to classical music at all, it’s as a social representation of elite class identity. And yet classical music is an enormously supple conveyer of social meaning.”

And so it is with Black classical music, and with the American Dvorak. When Allen Guelzo says that William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony and George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess “prove that Dvorak was right” when he prophesied that “Negro melodies” would foster a “great and noble” school of American classical music, Guelzo means that these artworks absorb and dignify core aspects of the American experience, enduring American truths. I comment:

“The story of Black classical music is both black and white. It includes W. E. B. Du Bois and William Dawson – and also Antonin Dvorak and George Gershwin. It also includes, in glorious fulfillment of Dvorak’s prophecy, Porgy and Bess – whose most fervent admirers included the members of the original 1935 cast.

“In the wake of Gershwin’s sudden, shocking death in 1937, a memorial concert was held at the Hollywood Bowl. The participants included Ruby Elzy, a gifted Black soprano who sang Serena in the original Porgy production on Broadway. Elzy, too, would die young – of a botched operation. She had been planning to sing Verdi’s Aida – for a Black opera company. Ruby Elzy’s rendition of ‘My Man’s Gone Now,’ at the Gershwin Memorial Concert, is the most extraordinary performance I know of any selection from George Gershwin’s opera. The aria itself is steeped in the yearning of the sorrow songs. The performance combines the bluesy pathos of Billie Holliday with the operatic splendor of a young artist on the cusp of what would have become a notable career. It is Ruby Elzy’s keening lament for the departed composer.”

You can hear Ruby Elzy sing “My Man’s Gone Now” – and the rest of the NPR feature – here (scroll to the bottom of the page for a time-code and use your cursor to naviage). And here’s an outline of the show:

PART ONE:

William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1934), why it matters, and why we don’t know it. With commentary by the late conductor Michael Morgan (8:00) and by Angel Gil-Ordóñez, who conducts the DC premiere this March with PostClassical Ensemble (9:00).

PART TWO:

George Shirley (12:05) remembers how Rudolf Bing desegregated the Metropolitan Opera. Allen Guelzo (18:00) ponders why American historians ignore the arts. Ruby Elzy sings “My Man’s Gone Now” (27:00).

PART THREE:

Excerpts (30:00) from PostClassical Ensemble’s Nov. 14 “narrative concert” – “The Souls of Black Folk” — at D.C.’s historic All Soul’s Church, with music by Harry Burleigh, Margaret Bonds, and Florence Price, plus readings from Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and Margaret Bonds. The participants include students from Howard University, and the Chorale of the Coalition of African-Americans for the Performing Arts. The final work is Price’s Suite for Brasses and Piano(1949), in its first performance (by pianist Elizabeth Hill with members of PCE conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez) in more than half a century (40:00).

–For more on PCE’s Black Classical Music Festival, click here.

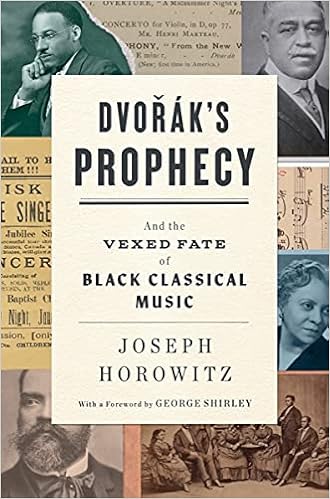

–For more on my new book “Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music,” click here.

–For more on the six “Dvorak’s Prophecy” documentary films just released by Naxos, click here.

Leave a Reply