For this weekend’s “Wall Street Journal” I have written an impassioned encomium for William Dawson’s thrilling “Negro Folk Symphony” of 1934 — still (alas) buried treasure:

In 1926 the African-American poet Langston Hughes wrote a seminal Harlem Renaissance essay, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” The mountain “standing in the way of any true Negro art in America,” he declared, was an urge “toward whiteness,” a “desire to pour racial individuality into the mold of American standardization, and to be as little Negro and as much American as possible.” Hughes cited, as an antidote, “the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul”: jazz and the blues.

Truly, America’s protean black musical mother lode has found expression in popular genres of its own invention—not string quartets, symphonies and operas. Nevertheless, a concurrent black classical music was pursued—a buried history today being exhumed. The notable interwar black symphonists comprise a short list of three: William Grant Still, Florence Price and William Levi Dawson. Their failure to excite attention was partly a consequence of institutional bias: African-Americans did not play in major American orchestras or conduct them. And there was also a pertinent aesthetic bias: The reigning modernist idiom was streamlined and clean, inhospitable to vernacular grit. It projected a sanitized “America.”

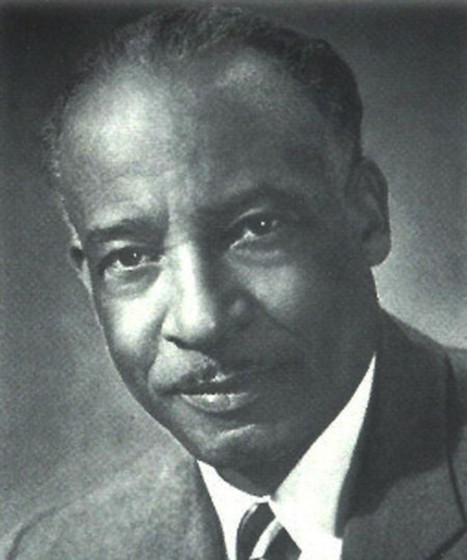

Over the past decade, both Still and Price have acquired new prominence. But the buried treasure is Dawson’s “Negro Folk Symphony” of 1934, whose three movements chart an ascendant racial odyssey. They notably embed such spirituals as “O Lemme Shine.” A heraldic horn call, symbolically linking Africa and America, binds the whole. Dawson (1899-1990), then 35 years old, had since 1931 led the Tuskegee Institute Choir. He had never before attempted a symphony.

The “Negro Folk Symphony” is anchored by its central slow movement, “Hope in the Night.” It begins with a dolorous English horn tune set atop a parched pizzicato accompaniment: “a melody,” Dawson writes in a program note, “that describes the characteristics, hopes, and longings of a Folk held in darkness.” A weary journey into the light ensues. Its eventual climax is punctuated by a clamor of chimes: chains of servitude. Finally, three gong strokes that prefaced the movement—“the Trinity,” says Dawson, “who guides forever the destiny of man”—are amplified by a seismic throb of chimes, timpani and strings.

If the symphony’s governing mold is European and (as Hughes put it) “standardized,” its energies remain uninhibited. Its lightning physicality of gesture—at one point, the music is intended to suggest “rhythmic clapping of hands and patting of feet”—exudes spontaneity, even improvisation. Dawson seizes the humor, pathos and tragedy of the sorrow songs of the cottonfield with an oracular vehemence. The best-known roughly contemporaneous American symphonies are the Third Symphonies of Aaron Copland and Roy Harris: leaner works favoring a modernist decorum. Dawson’s symphony, in comparison, exudes a wild folk energy driven by an exigent cause.

Notwithstanding its present obscurity, Dawson’s symphony received a galvanizing premiere by Leopold Stokowski and his Philadelphia Orchestra in 1934. Speaking from the stage, Stokowski called it “a wonderful development.” He also broadcast the symphony nationally, and took it to Carnegie Hall. Both in New York and Philadelphia, the young composer was repeatedly called to the stage. Far more remarkable is that “Hope in the Night,” with its culminating three-fold groundswell, ignited an ovation midway through every performance.

Leonard Liebling of the New York American hailed Dawson’s symphony as “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved.” Its most ardent admirers included W.E.B. DuBois’s future wife, Shirley Graham, who wrote to Dawson of her “joy and pride.” As the music historian Gwynne Kuhner Brown has pointed out, the “tumultuous approbation the ‘Negro Folk Symphony’ received from critics and audiences alike set it apart—not only from contemporaneous works by African-Americans, but also from most new classical music of the period.”

After that, the “Negro Folk Symphony” disappeared from view. Stokowski returned to the work in 1963, recording it with his American Symphony. Neeme Jarvi recorded it with the Detroit Symphony 31 years later. But performances and recordings of consequence remain few and far between.

The vital question becomes: “What if?” Dawson became a leading arranger of black spirituals, an honored éminence grise. But he had hoped to write a series of symphonies. He had hoped to conduct orchestras. Antonin Dvorak, teaching in New York in 1893, famously and controversially predicted that a “great and noble school” of American classical music would arise from the “Negro melodies” he adored. His African-American assistant, Harry Burleigh, turned spirituals into concert songs with electrifying success beginning in 1913. George Gershwin, in 1935, produced an opera saturated with the influence of “Negro melodies”: “Porgy and Bess,” arguably the highest creative achievement in American classical music (and this season’s smash hit at the Metropolitan Opera). No less than Dawson’s symphony, these lonely examples—however anathema to Langston Hughes’s famous admonition—suggest that Dvorak did not overestimate the music of black Americans. Rather, he overestimated America.

To read a pertinent essay on “black classical music,” click here.

I’ve played both the Dawson and the Still “Afro American Symphony” in Arizona orchestras. And I’ve head the Price 1st in concert here. The Price is pretty thin and weak; she wrote some better music but she was no symphonist. The Still is pleasant enough, but like a lot of other long-forgotten symphonies of that era, there’s not much substance. The Dawson is a riveting, thrilling work and challenging to play. And it will never become mainstream until the publisher puts the performance materials in shape. I recall many valuable rehearsal minutes being eaten up and wasted trying to get the score and the horrible parts lined up. Dawson made changes and cuts that are poorly indicated. The parts and score are handwritten and difficult to read at times. The entire work needs to be re-type set on computer and made available at a reasonable rental cost. Then, maybe, it will get more play time, but I still wouldn’t count on it – so many conductors just have to do the same old symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms, Dvorak, and Tchaikovsky for the umpteenth time.

Your thoughts about the symphonies of the 1930s is very interesting, though I feel that some of those works do have substance, such as William Grant Still’s second symphony, “Song of a New Race,” which is a more advanced work than its predecessor and, in my opinion, a far better work than the celebrated “Afro-American” Symphony, further diminished by his fourth symphony of 1947, an epic work that has received several performances from Thomas Wilkins and this respondent, who conducted performances of it in the 1990s with orchestras in Atlanta and New York.

Outside of African-American composers, I feel that Samuel Barber’s first symphony stands tall alongside the first symphony (“Symphony 1933”) of Roy Harris, which has more grit than the better-known Third, while Howard Hanson’s third symphony is an enigmatic work that follows the shadows of Sibelius more than the Second (“Romantic”). That the American symphonies of the 1930s seem to lack substance is not due in part to the composers but more of an unfair comparison to the symphonies produced by European composers in that same time period. Some of these symphonists remain barely-known to unknown entities to the American public, such as Norway’s Fartein Valen, Holland’s Matthijs Vermeulen, and a slew of British symphonists such as Vaughan Williams, Bax, Brian, Walton and George Lloyd.

As I mentioned in a separate post, it would be nice to see a critical edition of the Dawson produced, not only the revised version of 1951, but the original as well. Would it receive more performances? I think it would, but given the fact that you mentioned about conductors, especially young ones, they’d rather perform the umpteenth performance of a Mahler symphony than venture into unknown territory. The few who will risk doing this work and others like it are those who don’t seek fame for themselves, but only to be the messenger delivering music that cries to be heard.

First, you forgot one other African-American composer who wrote a symphony during this time period (1930s), namely James P. Johnson, whose Harlem Symphony has recently received some performances, due in part to Marin Alsop’s pioneering recording when she helmed the Concordia Orchestra. A recent performance by the Oakland Civic Orchestra attests to the importance of this work which is far more jazzy than the Still and, in many ways, more unbridled in terms of structure than either the Dawson or Price symphonies.

Second, what Marty mentioned above raises a very pertinent point regarding the Dawson. In the liner notes for Stokowski’s recording, the annotator (whose name escapes me at the moment) mentions that Dawson tried to obtain successive performances after Stoki’s premiere, but mentions that he had some frustrating experiences which I, along with many others, are curious about. That said, he put the symphony aside until the 1950s when, after a trip to Africa, decided to revise the work and infuse it with some of the rhythms he heard on his sojourn. This revised version is the one that Stokowski re-premiered and recorded with American Symphony Orchestra for American Decca (now currently available on Deutsche Grammophon). I concur with Marty that a definitive version should be made, not only of the revised version but the original one as well. At this point it should generate the interest of the right conductors who don’t want to do the umpteenth performance of Beethoven, Mahler and Bruckner (yeah, it seems that most conductors don’t do Tchaikovsky as often as they once did fifty years ago).