Books continue to be written about what it was like to live in Germany under Hitler. I wonder if any of the authors have auditioned Wilhelm Furtwangler’s wartime broadcasts with the Berlin Philharmonic. They should.

About a year ago, the Berlin Philharmonic issued a $250 box containing 22 CDs and a 180-page booklet. The contents comprise the complete surviving Furtwangler wartime broadcasts (1939-1945) in the best possible sound. Since most of these performances were recorded with magnetic tape (unprecedented at the time), the dynamic range and general fidelity are superior to the broadcast concerts Americans were (once) accustomed to hearing.

A specimen: the finale of Brahms’ Symphony No. 1 – the final work on Furtwangler’s final wartime broadcast (January 1945). This astounding document opens an audio window on life in Berlin when the city lay in rubbles. Since the orchestra’s historic home had been destroyed one year before, the venue was a faded operetta theater making do as a concert hall. The program had begun with Mozart’s Symphony No 40 — interrupted midway through when the lights went out. The audience stayed. An hour later, the concert resumed. Rather than returning to Mozart, Furtwangler skipped to the concert’s final scheduled work: the Brahms.

What was it like performing and hearing Brahms’ First under such dire circumstances? It becomes quite possible to find out.

It was my privilege to audition this singular performance with my longtime radio colleagues Bill McGlaughlin and Angel Gil-Ordonez on the most recent “PostClassical” webcast via the WWFM Classical Network. Brahms would not have recognized Furtwangler’s 1945 reading as Brahmsian. With its radical extremes of tempo and mood, it is not “true to the score.” Rather, it is true to the moment. What I glean is something I could not have predicted: not terror, but pride and defiance. Brahms’s clarion C major horn call, banishing the dark, here becomes an iteration of “the real Germany,” stalwart in the face of barbarism and insanity.

We should stop presuming to judge Furtwangler’s decision to stay rather than emigrate. His conviction that in doing so he was preserving a precious legacy is here made wholly tangible and intelligible.

Richard Taruskin, in one of three valuable essays in the Berlin Phil booklet, ponders “Expressivo in Tempore Belli: Considering the Conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler” – the most empathetic writing I can recall from this prolific music historian. Taruskin writes of Furtwangler:

“His definition of Deutschtum (Germanness) was elastic enough to encompass his Jewish countrymen. In an address commemorating Mendelssohn’s centenary in 1947, which was coincidentally the year of his denazification, Furtwangler ended with the explicit declaration that ‘Mendelssohn, Joachim, Schenker, Mahler – they are both Jews and German,’ and then added heartbreakingly: ’They testify that we German have every reason to see ourselves as a great and noble people. How tragic that this has to be emphasized today.’”

As Taruskin stresses, Furtwangler’s notion of Werktreue – textual fidelity – was not Toscanini’s or Stravinsky’s. Rather, it was Wagner’s: not literal adherence to the composer’s notated instructions, but an act of extrapolation discovering the “idea” of the piece. And, I would add, that idea could prove malleable accordingly to time and place: conditions Furtwangler channelled with uncanny sensitivity and communicative force.

As I mentioned on the “PostClassical” webcast, I once had occasion to share with my wife, Agnes, a 1951 Furtwangler performance of Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony. This justly famous Radio Cairo broadcast does and does not resemble Furtwangler’s 1938 studio recording. The difference is the memory of war. Tchaikovsky’s symphony seems — as Agnes remarked – “about World War II.” The composer’s autobiographical heart-ache and Weltschmerz are here transformed into a dire existential statement transcending the personal.

Shostakovich is not irrelevant. He, too, possessed a genius for channeling the moment. The legendary first Leningrad performance of Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, in the midst of a murderous Nazi siege, was cathartically empowering for a great city facing extinction. Shostakovich’s Seventh was a direct product of those circumstances. Brahms had never intended his First Symphony as a survival strategy. But that is what Furtwangler made it become.

The other discovery of our webcast was a Schubert passage. His “Great” C major Symphony was a Furtwangler specialty. The work itself is polyvalent, both gemutlich and demonic. Its second movement, marked “Andante con moto,” is and is not a “slow movement.” Rather, it is a march with trumpet tattoos in alternation with intimations of the sublime. Furtwangler’s wartime broadcast, in December 1942, is never gemutlich. Bill McGlaughlin, in the WWFM studio, memorably characterized its massive climax as “a firestorm.” Here Schubert’s march is a juggernaut hurtling toward an abyss. The abyss is a silence of three beats. In Furtwangler’s reading, the silence lasts eight seconds: an eternity. Reacting in the moment, Bill’s voice quavered when he said: “This time we really broke it; we really broke civilization.” And he characterized the music finally lifting the silence – the tenuous pizzicatos, the tender cello song – as an act of dazed consolation.

Something awful is conveyed in this Furtwangler reading of Schubert’s climax. It is, I suppose, something Schubert – a seer — may have distantly or subliminally glimpsed. But it is Furtwangler, channeling the moment, who has uncovered it. This reading no more conforms to our notions of “Schubert” than those Brahms and Tchaikovsky performances support received wisdom. They instead affirm that music has no fixed meaning, that great works of art are so profoundly imagined that their intent and expression forever mold to changing human circumstances.

For more on Furtwangler, see my blogs of Aug. 4 and 8, 2018.

A LISTENING GUIDE FOR THE WEBCAST:

PART ONE:

10:18 – Brahms Symphony No. 1: finale (January 1945)

39:40 – Bruckner Symphony No. 9: first movement (October 1944)

PART TWO:

00:00 – Beethoven Symphony No. 5: first movement (September 1939)

7:09 – Beethoven Symphony No. 5: movements three and four (September 1939)

21:38: — Schubert: Symphony No. 9: second movement (December 1942); to hear the silence, go to 32:00

45:08 – Schubert: Symphony No. 9: fourth movement (December 1942)

Well done, Thanks for this. I look forward to listening to this set.

A fine, fine article. The referenced second movement of the Schubert was absolutely terrifying. I’ll never hear the piece again without thinking of this performance… and Furtwangler’s conviction of preserving “a precious legacy” by remaining in Nazi Germany.

Music in wartime. On 12 April 1945, members of the Hitler Youth distributed cyanide pills to audience members during the last concert of the Berlin Philharmonic. The purpose was to help people avoid mass rape by the invading Soviets who were acting in revenge for the massive death and destruction Germany had caused in the USSR. At that point, mass rape and mass suicide had become a reality and were part of the unspeakable nature of the war. How does one situate classical music in a contexts like these?

This type of thing just makes me curious as more and more Classic Furtwangler recordings from before, during, and after the war are now being distributed….with his Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, and yes Wagner taking a great deal of notice. I just never understood how he got DE-NAZIFIED so fast….able to continue conducting in Germany and Austria so quickly. I mean perhaps he denounced it but he sure PROFITED from the Nazi Regime…..I was under the understanding that he was one of Hitler’s favorites. I’ve often wondered about Karajan as well and the evidence is there that he too had Nazi membership…as a younger man—he might have felt that he HAD too but Furtwangler was a veteran celebrity Conductor, he stayed put and yet just continued on…..he was OFFERED the New York Phil after Toscanini…(when they hired the young Barbirolli instead) but he turned it down thinking that American Audiences wouldn’t be too responsive to a German…or so the story goes.

I plan to audition these soon as I do most Furtwangler recordings recorded after the Electric era started, but I’ve always wondered about that 1946-1947 period.

My favorite of the Furtwangler wartime broadcasts is Bruckner 5, it’s the one Furtwangler wartime performance I am absolutely sure has never been bettered in any context at all. It’s Bruckner’s greatest symphony and while a couple performances come close: including some you wouldn’t expect (look up Volkmar Andreae’s Bruckner 5 if you’ve never heard his Bruckner….), but while I can think of other performances in any other work that I might want to listen to more, in Bruckner 5, Furtwangler is without peer.

I think the best way to think of Furtwangler in those circumstances is to let the question remain ambiguous. Art isn’t so important that Furtwangler lending his prestige to the Nazis is worth a couple great performances of Bruckner and Brahms, but we fortunately have not yet understood what it was like to live under those conditions, and until we do, I don’t think we’re in a position to rule one way or the other about what was acceptable behavior. Horenstein put it best about Furtwangler: ‘he understood that a Germany without Huberman would be a poorer place, but I doubt Furtwangler ever gave much thought to the small-town piano teacher.’

To me, that comes through as the ultimate trouble with Furtwangler’s art. The ordinary side of music, the high spirits, the fun, is missing. In a composer like Wagner or Bruckner, this is not much of a weakness, but in Beethoven, it can be deadly in many of the works that Furtwangler is most celebrated: I could never warm to his performances of either the Eroica or the Ninth, to me they’re both impossibly slow, bombastic, humorless. I feel differently about F in the fifth and the seventh, but surely there’s more to Beethoven than Furtwangler finds.

There’s no question in my mind that Furtwangler is one of the true greats, but the cult of Furtwangler strikes me as a little creepy. It sometimes almost seems as though he attracts such worship because his performances are so lofty that they’re almost inhuman. They’re awesome experiences, but ordinary everyday human emotions are a little rarer than they are in many other greats, and while his legend still doesn’t obscure a couple greats like Klemperer or Lenny, his cult overshadows a lot of golden age conductors who are just as great if not better and should be vastly more feted as both musicians and sometimes as humans. All this attention on Furtwangler obscures attention that could be given to Mengelberg, Bodanzky, Panizza, Monteux, Walter, Beecham, Coates, Stokowski, Abendroth, Ansermet, Paray, de Sabata, Busch, Scherchen, Golovanov, Mitropoulos, Munch, Barbirolli, Jochum, early Celibidache, Fricsay, Kubelik, Kondrashin…. at least to me, the list of Furtwangler’s equals is surprisingly long….

Wonderful article. My thoughts on the maestro:

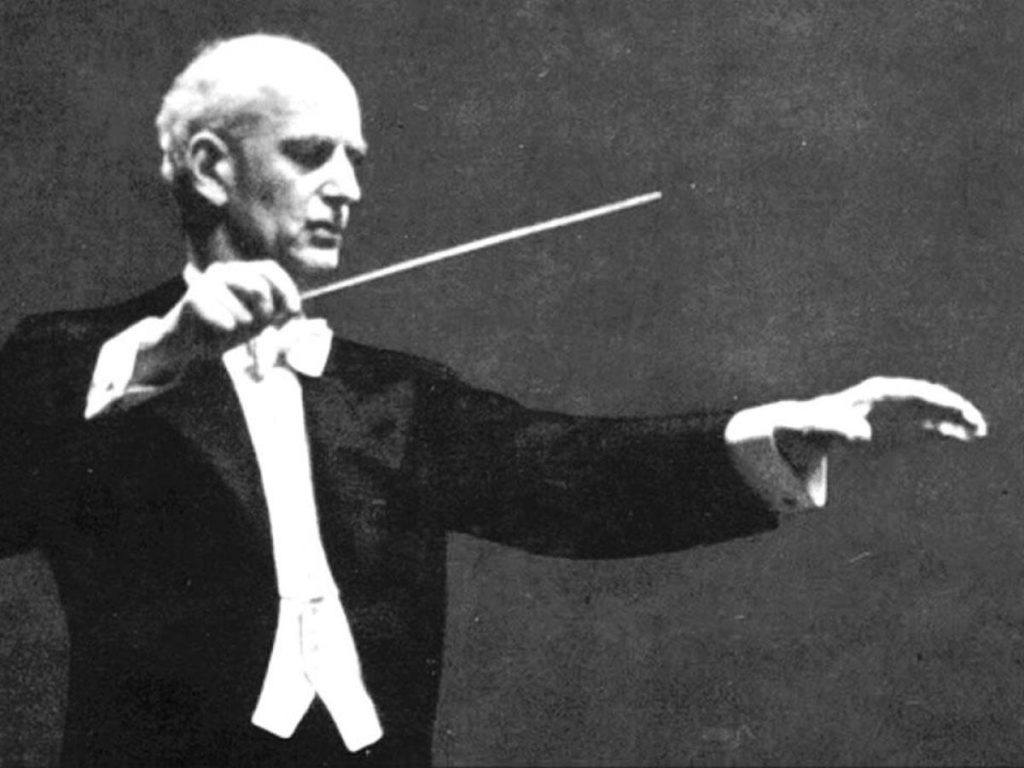

Films of Furtwangler conducting reveal a caricaturist’s dream. His elongated figure was capped by a head too small for the length of his neck. On the podium, he moved like a wet strand of vermicelli tugged about by the strings of an unseen puppeteer. His left arm, in particular, dangled and flapped as if boneless. He jerked around like a seismometer registering disturbances from another world. His almost unseemly physical flexibility was translated into the flexibility of his interpretations which distended or concentrated the music, like long and short contractions in childbirth, according to what he thought the music was trying to say. This interpretive approach may not be to everyone’s liking. Some critics say that he was pulling the music like taffy. Imprecision was part of his vocabulary because he found it expressive, and he abhorred a regular beat. He once stormed out of a Toscanini concert, exclaiming “bloody time-beater.”

Whatever his eccentricities, I have been astonished by the extraordinary number of revelations Furtwangler provides in works that I know well, things I have never heard before in pieces like the Brahms Symphony No. 3 and the Schumann Spring Symphony. Nothing passes along by rote. Nothing is routine. Furtwangler is always doing something interesting, often daring, and with the utmost conviction. For Furtwangler, the notes were mere semaphore, only crudely indicating the composer’s intent. Furtwangler wished to recapture the experience to which the notes were meant to give expression. Perhaps he occasionally invested the music with more passion and drama than it could bear – oh, Felix culpa! – but he was always searching for the deeper, transcendent significance hidden behind the notes. It is no surprise that his approach worked best with composers possessed of a transcendent vision, like Beethoven or Bruckner.