Of the interesting emails I received in response to my American Scholar review of Porgy and Bess, the most informative was from a singer with considerable experience doing Porgy on stage. He wrote:

“As challenging as it was for me to sing most of Porgy on a cart (the rest of the time I was on my knees), there is no substitute for singing and viewing the world from that perspective.”

Gershwin intended Porgy to be pulled by a goat while sitting on a cart. He is a man who cannot stand up. Today Porgy is typically ambulatory on crutches: mobilized. I now realize this is one of the reasons that Eric Owens’s portrayal, at the Met, “starts too strong.” It is because he is erect.

Early on, Porgy sings: ““When Gawd make cripple, He mean him to be lonely. He got to trabble dat lonesome road.” This crucial self-observation only really registers when Porgy “views the world” from below. And the goat reinforces his distance from normal human company.

Also — as John Mauceri just pointed out in another email to me — if Porgy can walk on crutches, he can go to that picnic.

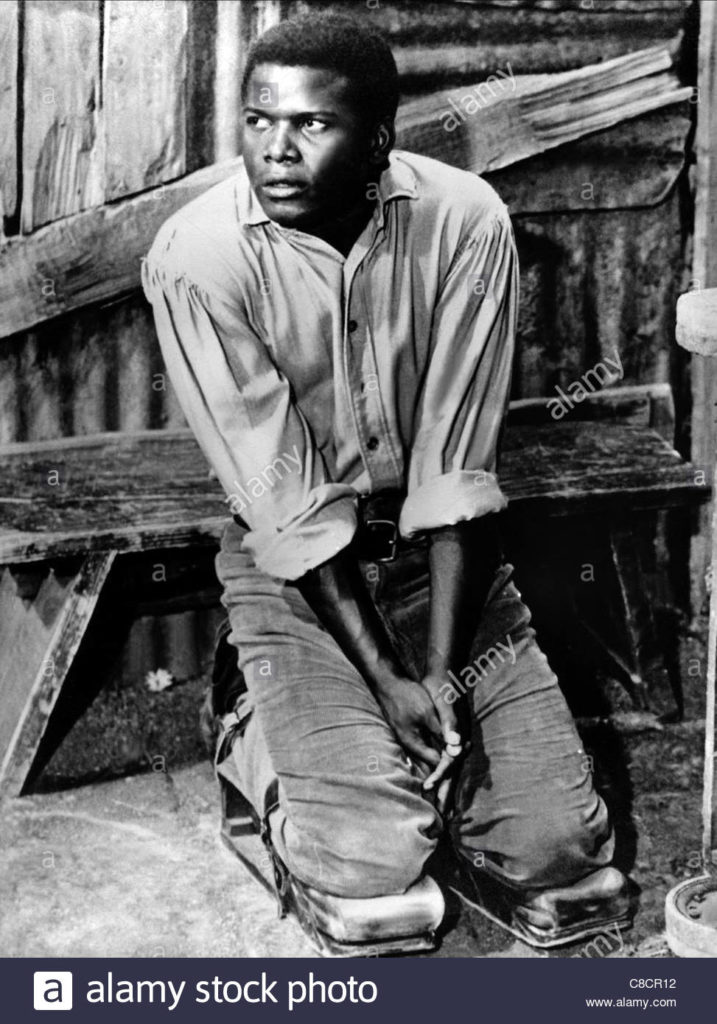

Additionally, re-reading my review, I wish I had been more explicit about the regrettable impact of Sidney Poitier’s performance in the 1959 Otto Preminger film version of Gershwin’s magnificent opera. Poitier is so manifestly uncomfortable in this role that his portrayal reads as a critique. However subliminally, we are made to believe that Gershwin has created an objectionable “stereotype.” So far as I can ascertain, this is a claim mainly originating in the fifties: long after the opera’s premiere and initial reception.

It was my privilege to speak with Poitier on the phone when I wrote “On My Way” – The Untold Story of Rouben Mamoulian, George Gershwin, and “Porgy and Bess.” He was perfectly candid. He never sought to play Porgy. Rather, Lillian Schary Small, a sometime associate of Poitier’s agent Martin Baum, sought and acquired it for him. Samuel Goldwyn, who initiated and produced the film, was too star-struck to realize what he was doing (his equally risible first choice had been Harry Belafonte). Ultimately, Poitier agreed only on condition that he also be cast in a film he coveted – The Defiant Ones. Of Porgy and Bess he said to me: “I don’t talk about it. I’ve dismissed it. I did it, I didn’t want to do it. I did not want to be stopped in my tracks.’

I also had occasion to discuss Preminger’s film at length with the late Andre Previn, who as music director both conducted and arranged Gershwin’s score. What Previn had to say (a lot) is recounted in detail in my book. Of Poitier he commented: “Sidney told me he was ‘tone-deaf.’ I said ‘C’mon.’ So I sat down at the piano and played two notes, one at the top of the keyboard, one at the bottom. ‘Now which note is higher?’ I asked Poitier. ‘It’s your job to tell me,’ he answered.”

The gruesome tale of how Samuel Goldwyn hired and fired Rouben Mamoulian, then replaced him with the martinet Preminger — also in my book, ,thanks to Mamoulian’s copious documentation — itself deserves to be a movie, with secondary parts for Poitier, Previn, and Dorothy Dandridge (Preminger’s ex-girlfriend, whom he verbally abused on the set). It could more productively engage with Porgy and Bess – and its attendant issues of race and American identity — than have any number of stage productions. (I have a five-page treatment in my pocket).

Leave a Reply