In 1893 Antonin Dvorak, teaching in New York City, predicted that a “great and noble school” of American classical music would arise from America’s “Negro melodies.” Dvorak’s prophecy was instantly controversial and influential.

But the black musical motherlode migrated to popular genres known throughout the world. American classical music stayed white. The reasons are both obvious and not.

This is the topic of my book-in-progress Dvorak’s Prophecy. In the current issue of The American Scholar, I encapsulate my findings. I identify two factors: institutional racism (obvious) and modernism (not so obvious).

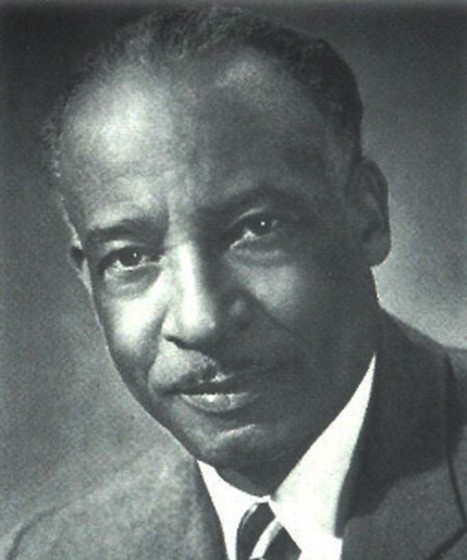

What’s the pertinence of Aaron Copland’s poor opinion of “Mr. Gershwin’s jazz”? Of Virgil Thomson’s view that American folk music was fundamentally white? Of Leopold Stokowski’s credible assertion that William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony (1934) marked “a wonderful development in American music”? And whatever happened to that formidable symphony, greeted by one eminent critic as “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved”?

Here’s a taste of my article:

“The reigning paradigm for a modernist ‘American school’ had no more use for sorrow songs than for Gershwin or Ives, not to mention the ‘black’ symphonies of Still, Price, or Dawson. The same fate would have befallen the most popular, most iconic American concert work – Rhapsody in Blue– if Paul Rosenfeld had held sway. Writing in The New Republic, the high priest of American musical modernism detected in Gershwin the Russian Jew a ‘weakness of spirit, possibly as a consequence of the circumstance that the new world attracted the less stable types.’ Rosenfeld vastly preferred the ersatz Piano Concerto that Copland produced two years after Gershwin’s ‘hash derivative’ Rhapsody. Elevated by Copland, jazz had at last ‘borne music.’

I conclude:

“Does William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony signify an ephemeral footnote or a crucial squandered opportunity? In the history of twentieth century American music, the black musical motherlode migrated to popular genres with magnificent results – in part through natural affinity; in part because it was pushed. Might American classical music have canonized, in parallel, an ‘American school’ based in the black vernacular? I believe we may be about to find out.”

Read the entire article here. To hear a related podcast (with musical examples), click here.

Back in the 1980s the orchestra I managed, the Orchestra of Illinois (Chicago’s ‘second symphony orchestra’ at the time) commissioned a young African American composer who was mentored by Gunther Schuler who conducted the work. Everyone was impressed with it. Our intention was to continue in that direction. But then I left the orchestra field a year later, and it eventually folded.

I returned to my primary field, the regional theatre where I was fortunate enough to work with August Wilson among other black playwrights. While I’m retired now, I think it’s a shame that an “August Wilson” didn’t emerge in the orchestra field. The people in that world tended to be on the conservative side unlike theatre. And systemic racism was certainly a major factor.

To this day I wonder what happened to that young man. Maybe I’ll find him in your book!

Bill