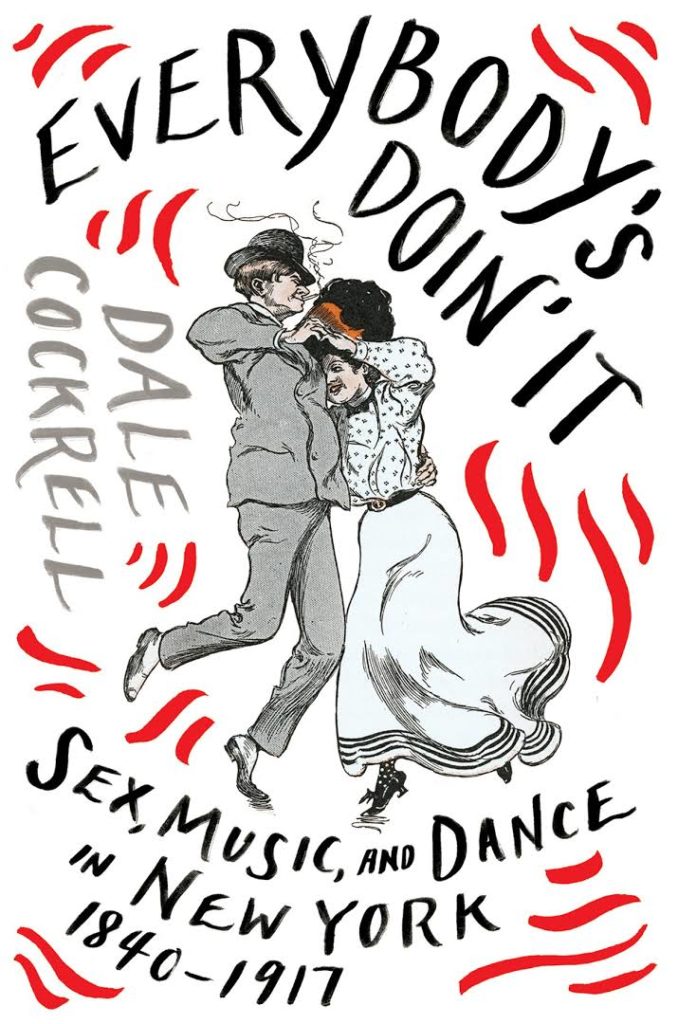

Dale Cockrell’s “Everybody’s Doin’ It: Sex, Music, and Dance in in New York 1840-1917” is a book that will bring to wider attention the scholarship of one of America’s most original music historians — someone whose work fearlessly challenges conventional wisdom. It was my pleasure to review this new Norton release in this weekend’s “Wall Street Journal”:

On his first trip to New York, in 1835, Davy Crockett discovered in the drinking cellars of the Five Points “such fiddling and dancing nobody ever saw before in this world. I thought they were the true ‘heaven-borns.’ Black and white, white and black all hug-em-snug together, happy as lords and ladies.”

Subsequent reporters, including armies of undercover cops, documented not only further racial intermingling in New York’s brothels and backroom saloons but also nudity, cross-dressing and “tough dancing”—and did so with a deadpan acumen both thorough and hilarious. The high-kicking can-can, appropriated from Paris, was “extravagantly indecent”; one 1885 incarnation, in an Eighth Avenue dive, degenerated into a “drunken orgie.” While two women danced, their companions snatched at their clothes until they “literally danced in nothing except hats, shoes, and stockings.” A 1902 film shows “A Tough Dance at McGurk’s” in which Sailor Lil begins whirling while her partner Kid Foley’s hands slide down her backside, after which both dancers toss themselves on the floor and roll on top of each other. As the music historian Dale Cockrell summarizes: “Few, if any, decades in the history of American dance featured a wider array of wildly provocative dances than the 1910s.” In 1912 alone, investigators identified such species as the hoochie koochie, the grizzly bear, “skirt & muscle dancing” and an airborne “exhibition dance” in which a female was twirled clinging to her partner’s neck.

That this world of sex, dance and music was interracial is crucial to Mr. Cockrell’s book “Everybody’s Doin’ It: Sex, Music, and Dance in New York, 1840-1917.” It makes the connection to his scholarly specialty and passion: American popular music and its black vernacular roots. In an earlier, essential study, “Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World” (1997), he brilliantly elaborates an unpopular truth—that, early on, blackface music-making was not necessarily racist. Rather, it could be about class: a means of empowering the little guy in a world of capitalist snobs and prudes. And Mr. Cockrell, accordingly, is an eloquent advocate for the most gifted, most popular pertinent composer: Stephen Foster, in whose songs of loneliness and hardship (though sung in exaggerated black make-up by white performers) he finds an empathetic voice arising from Foster’s own marginality.

In “Everybody’s Doin’ It,” this theme returns newly embroidered and contextualized. Assessing the white minstrel singer whose signature blackface song was “Zip Coon,” Mr. Cockrell calls George Washington Dixon (1802-61) “surely one of the most complex, enigmatic, and colorful figures in American history.” He continues: “There is no question that the skeleton around which [the blackface minstrel show] was built was the denigration of black people. . . . And—too often forgotten—there is no question that its enormous, century-long appeal was because of the music and dance that gave it flesh. That music and dance . . . was an expression of urban, lower-class, dance-hall and brothel culture. To the throngs on the stage of the Bowery Theatre, ‘Jim Crow’ belonged to them. Who would have thought that lower-class music and dance deserved a place on the legitimate stage? . . . ‘Zip Coon’ belonged to them as well. The song was of them, and once Dixon sang their song . . . their point was made: our music; we made it; we belong here.”

In Mr. Cockrell’s account, minstrel extravaganzas at the Bowery overlapped in audience and affect the battered pianos, cracked cornets and raucous tambourines of red-hot “concert saloon bands” down the street. And both inculcated an American popular music that after World War I would sweep the world. An offspring of plantation song, the blues “joined oppressed people together into a single mind.” “Born in despondency,” it sang “loudly of hope.”

But by the time jazz invaded Paris and Berlin, New York’s brothels were in steep decline, their biracial music and dance squelched and sanitized. A series of clean-up exercises culminated with a Committee of Fourteen formed in 1905. Its founding members included leaders of the city’s major religions. Its financial bulwarks included John D. Rockefeller Jr., J.P. Morgan, George Foster Peabody and George H. Putnam. Its undercover detectives would chat and imbibe, even sing and stroke a barroom piano before heading upstairs. A representative report: “I sat on the edge of the bed and was talking to her and she kept saying hurry up. . . . There is others that want to be f— as well as you. I told her that I was not in a hurry and that I did not want to f— in a hurry.”

Some 1,200 establishments were thus inspected. Many were successfully shut. As incriminating evidence of corruption and vice explicitly included racial intermingling, a “de facto color line” was enforced. Marshall’s Hotel on West 53rd Street was among the most popular nightspots in town, “a vibrant black and tan that was the epicenter of New York’s black bourgeois life”; the clientele included James Weldon Johnson, James Reese Europe, Paul Laurence Dunbar and W.E.B. Du Bois. Investigators reported how white women met their “colored lovers” there. Marshall capitulated, newly separating his patrons by color—a Jim Crow sea change. The tide of social activism, Mr. Cockrell writes, changed the city’s “approach to morality.” Concurrently, its music changed. Ragtime made way for jazz, purveyed by an army of displaced black and white musicians who had lost access to a secure demimonde economy. “Music as a public, big-space, segregated experience” resulted.

A memorable epilogue to “Demons of Disorder” reveals how Mr. Cockrell came to chronicle all this in two linked books. He grew up in rural Kentucky, where—stereotypes notwithstanding—he acquired black friends and a notion of racial equality enforced by his parents. Later, in the north, he encountered less comfortable racial attitudes among whites more entitled than he had been. In his 20s, he taught in Africa before joining the music faculty of Middlebury College. His personal odyssey turned him into a populist on the left—in today’s America, an honorable endangered species. Mr. Cockrell’s identification with his interracial childhood peers fires his scholarship to this day. “Everybody’s Doin’ It” is a book to read and ponder.

MORE ABOUT “EVERYBODY’S DOIN’ IT” (NOT FROM MY “WALL STREET JOURNAL” REVIEW):

Everybody’s Doin’ It documents three findings. The first is about the musical legacy of blackface minstrelsy. The second is about racial intermingling in New York City at the turn of the twentieth century. The third is about the culture of brothels. All three challenge conventional wisdom.

Cockrell writes: “Prostitution was a large, highly developed urban industry throughout the United States from the Jacksonian Era up to World War I.” What he means by “large” is that as of 1858 commercialized sex was New York City’s second largest industry, right after textiles, with one prostitute for every fifty-two males. The numbers went up after that.

The topic is complex. For some women, prostitution was their last best hope. It was, Cockrell generalizes, seldom “unalloyed exploitation” or “a way for women to be empowered.” And the world of brothels was about other things as well. It is in these other things – bristling with social and creative energies – that Cockrell surprisingly discovers a defining American milieu.

Remarkably, he has documented that in Manhattan musicians charged with keeping customers dancing comprised something like thirty per cent of the total male musician population. The police reports he has exhaustively culled further disclose the kind of American dancing that this American music impelled.

To call it “erotic,” in shorthand, would be both accurate and evasively incomplete.

Leave a Reply