Faced with a twelve-hour drive, with wife and dog, from Manhattan to the idyllic Brevard (North Carolina) Music Festival, I threw some CDs in the car.

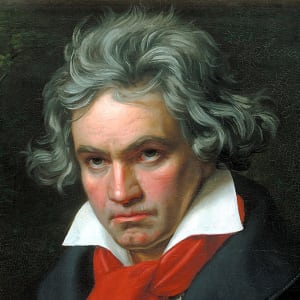

I chose Fidelio because I had been eager to re-experience Beethoven’s opera since encountering David Lang’s Fidelio-for-today, A Prisoner of State, premiered by the New York Philharmonic as a season finale concert opera. This minimalist distillation ignited a standing ovation. But I wanted to go back to the real thing.

The Fidelio I own is the famous 1962 EMI recording, conducted by Otto Klemperer, with Jon Vickers as Florestan and Christa Ludwig as Leonore. I hadn’t heard it in decades.

I skipped act one because act two is better. Agnes silenced her cell phone. Teddy was asleep in the back seat.

Florestan was one of Vickers’ signature roles. His specialty was the outsider. I knew that re-visiting his aching rendition of Florestan’s dungeon aria, beginning act two, would grip the car.

But I was unprepared for the rest. Beethoven tinkered for years with Fidelio, struggling to get it right. But, as I now discovered, act two proceeds with an inexorable logic, rising from blackness to refulgent light. Wondrously, Beethoven ascends by degrees. Then, when the arc is at its peak, he peaks some more: “O Gott! o welch ein Augenblick!”

The sudden linchpin in this progression is when Leonora exclaims “Tödte erst sein Weib!” (“First kill his wife!”). The moment – the lad Fidelio is revealed to be the heroine Leonora — is transformational. Agnes began passing me paper towels to dab my cheeks as we rode into West Virginia.

In general, I mistrust studio recordings of opera. But this Fidelio is alive at every moment. And it isn’t just Vickers and Ludwig, as the unconquerable husband and wife. Gottlob Frick, as Rocco, bears unforgettably humane witness, deploying his sepulchral bass (an increasingly rare species) at half voice.

When it ended, I struggled to speak. All I managed to say was: “It’s over.” Agnes understood that I was referring not to the disk in the CD player. I meant Klemperer, Vickers, Ludwig, Frick, Beethoven – an aesthetic experience overpowered by empathy. There will never again be a Fidelio like this.

In 1927, Klemperer was asked how best to celebrate the Beethoven Centenary. “Don’t play any Beethoven for a year,” he answered.

We have another Beethoven anniversary coming up – 2020 marks 250 years since his year of birth. I think I know how PostClassical Ensemble will celebrate. We’ll invite our patrons to communally experience that 1962 Klemperer recording.

That I cannot imagine a more compelling Beethoven experience in the year 2020 says it all.

There will never again be a Fidelio like it, but we have a Fidelio even more human than that one. Bruno Walter 41 at the Met, his first performance after moving to the US permanently. Klemperer is wonderful, stately humane, Walter is ecstatic.

FIDELIO is the perfect example of how there are no perfect, definitive recordings of any given work – especially a masterpiece, where there are so many prisms through which it can be experienced. My first recording of FIDELIO was on the old American DECCA label (not to be confused with London/Decca) the RIAS conducted by Eugen Jochum and starring Leonie Rysanek and Ernst Haeffliger. The supporting cast consisted of Fisher-Dieskau, Gottlob Frick, and Irmgard Seefried. Youngsters may not realize what a starry cast this was, and these singers didn’t disappoint. Rysanek with her blazing top notes was simply thrilling. Other recordings of the opera soon appeared in the record catalogue and they each had considerable strengths and also their disappointments.

Some featured big voiced, heroic singers while others featured more lyric voices.in the lead roles. Together with conductors – a veritable Who’s Who of the conductor’s world, no recording is without its strengths.