Could Harry Burleigh — Antonin Dvorak’s African-American assistant — be considered an Uncle Tom?

These days, the question comes up whenever Burleigh comes up: it’s a symptom of the times, and of our crazy obsession with “cultural appropriation.”

And it is addressed head-on over the course of the most recent PostClassical Ensemble WWFM podcast, featuring a supreme exponent of the spiritual in concert: the African-American bass baritone Kevin Deas. (To see what he and others have to say, hang on for a dozen paragraphs — or simply access the podcast at https://www.wwfm.org/post/postclassical-feb-15-deep-river)

I would call Harry Burleigh (1866-1949) a forgotten hero of American music. It was mainly Burleigh who turned spirituals into concert songs to be sung alongside the Lieder of Schubert and Brahms. The project became controversial during the Harlem Renaissance – Carl Van Vechten, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston were among those who worried or asserted that Burleigh vitiated the music he adapted. And today Burleigh is controversial all over again.

Because I have long celebrated Burleigh in public performance, because I often have occasion to lecture on American music, I can cite many examples from personal experience. There was, for instance, the impressively poised African-American freshman at a Midwestern college who opined that “just because Burleigh was black, he didn’t necessarily have the right to do that.” As she had never heard of Marian Anderson, I played for the class a recording of Anderson singing Burleigh’s iconic “Deep River” arrangement. After that, I shared with them Anderson’s historic Lincoln Memorial concert of 1939, when – having been denied access to Constitution Hall because of the color of her skin — she sang Burleigh for more than 75,000 listeners.

It must be acknowledged and pondered that Burleigh frequently inhabited a white milieu. His arrangements were initially sung by famous white recitalists – because in 1917 famous vocal recitalists were white. He himself sang in synagogue and church choirs that were mainly white. His friends included J. P. Morgan, at whose funeral he sang.

By way of background: Not so very long after Dvorak and W.E.B. Du Bois extolled the sorrow songs as the likely fundament for a future American music, artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance scoured the African-American musical past. One starting point was the cottonfield. One outcome was a now legendary debate over the uses of a past known and acknowledged, wracked with pain and yet protean with possibility.

It is little remembered that, like Dvorak, Du Bois was a Wagnerite. As a graduate student in Berlin, he came to know and embrace The Ring of the Nibelung. In the tradition of Wagner, Herder, and other German theorists of race, he linked collective purpose and moral instruction to “folk” wisdom: the soul of a people. To Du Bois it was merely obvious that for black Americans the sorrow songs comprised a usable past that, subjected to evolutionary development, would yield a desired native concert idiom — the same trajectory anticipated by Dvorak and Burleigh. Formal training and performance, for Du Bois, did not impugn the authenticity of folk sources; rather, a dialectical reconciliation of authority and cosmopolitan finesse would result. Concomitantly, ragtime, the blues, and jazz threatened Du Bois’s cultural/political agenda. A child of the Gilded Age, born in tolerant Massachusetts in 1868, he endorsed uplift.

Alain Locke, sole offspring of a well-to-do Philadelphia family in 1885, was like Du Bois a distinguished black Harvard graduate. His philosophy of the “New Negro,” a signature of the Harlem Renaissance, aligned with Du Bois’s high-cultural predilections. “Negro spirituals,” Locke wrote in 1925, could undergo “intimate and original development in directions already the line of advance in modernistic music. . . . Negro folk song is not midway in its artistic career yet, and while the preservation of the original folk forms is for the moment the most pressing necessity, an inevitable art development awaits them, as in the past it has awaited all other great folk music.” Like Du Bois, Locke championed the tenor Roland Hayes, who succeeded Burleigh as the pre-eminent exponent of the spiritual in concert. Like Du Bois, he mistrusted the popular musical marketplace in favor of elite realms of art.

The opposing camp included Harlem’s loudest white cheerleader: Carl Van Vechten, who deplored Hayes’ refinements in favor of Paul Robeson’s “traditional, evangelical renderings” of the Burleigh arrangements. This – and Van Vechten’s celebration of the blues and jazz – ignited a furious rebuttal from Du Bois, who discerned a decadent voyeur in love with black exoticism. But Van Vechten’s revisionism was supported by the black writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Many of Hughes’s poems key on the dialect and structure of the blues. He heard in jazz “the eternal tom-tom beating of the Negro soul.” He deplored the “race toward whiteness” in the uses of black music. Hurston deplored a “flight from blackness.” She heard concert spirituals “squeezing all of the rich black juice out of the songs,” a “sort of musical octoroon.” If to Hurston the sorrowful spirituals Du Bois espoused sounded submissive, to Locke the blues sounded “dominated” by “self-pity.” Pitting authenticity against assimilation, the debate identified conflicting vernacular resources, old and new, rural and urban.

If certain black Americans rejected American classical music, American classical music rejected them. Even though Hayes and Robeson enjoyed phenomenal success in recital, opera companies and orchestras resisted singers and instrumentalists of color. Notoriously, Marian Anderson had to wait until 1955 to sing at the Metropolitan Opera – an invitation engineered not by native-born Americans, but by the immigrants Sol Hurok, Rudolf Bing, Max Rudolf, and Dmitri Mitropoulos.

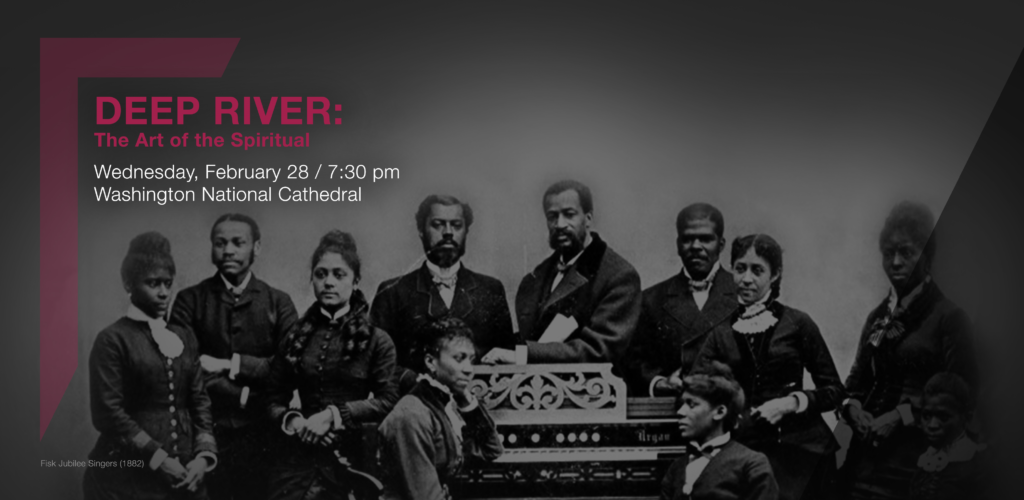

All of which came up in the course of our two-hour “PostClassical” podcast: “Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual,” celebrating Burleigh and his legacy. Here is what Kevin Deas sounds like singing Burleigh’s fervently inspired transformation of “Steal Away,” a performance at the Washington National Cathedral that I was privileged to accompany at the piano:

“Steal Away” (arr. Burleigh) sung by Kevin Deas (Horowitz, piano)

And here, from the same podcast, is what Kevin Deas had to say about cultural appropriation:

“I am from a different generation. I grew up in the sixties and the seventies when the message was ‘everyone can do everything.’ I felt I was blessed because my dad was in the military – so I grew up in a melting pot. I grew up among people of all ethnicities. It never occurred to me that as a black person and a budding artist I needed to take a specific direction. I wanted to see what my instrument was inclined to do and to follow that. And my sound wasn’t really right for gospel. I was drawn to classical music. To think that I was ‘appropriating’ German Lieder as an African-American would never have occurred to me. No disrespect to other genres, but that’s where my voice took me. I never questioned the authenticity of my expression. And I was very happy to come back to the spiritual relatively late in my career and have a new and different approach. My only expectation was to improve my art, and to evolve with it.”

In the ensuing conversation – you can listen to it – I cited the disapproving views of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Reacting to that, Kevin said: “I couldn’t disagree more.” To which Bill McGlaughlin, who inimitably hosts “PostClassical,” added: “Neither Langston Hughes nor Zora Heale Hurston were musicians. When real musicians get ahold of [music they embrace], they’re going to go where they’re going to go – no matter what the philosophies are. Your gonna follow what’s in your ear and in your heart.”

Following this exchange, we listened to Harry Burleigh sing his own arrangement of “Go Down Moses” (a 1919 recording), followed by “Go Down Moses” as arranged in 1941 by Sir Michael Tippett – i.e., a white British composer. Bill likened Tippett’s stirring appropriation to “Picasso looking at a work of Velazquez and making it into a brand new piece.” Angel Gil-Ordonez called it “a beautiful appropriation of extraordinary material.” And I remarked that Tippett’s “Go Down, Moses” precisely fulfills Alain Locke’s aspiration that African-American spirituals undergo “original development” in “the line of advance in modernistic music.” You can hear it all here:

Burleigh sings “Go Down, Moses” (1919); Sir Michael Tippett’s choral arrangement of “Go Down, Moses” (Deas, Gil-Ordonez, Cathedral Choir)

Our podcast, featuring live PostClassical Ensemble performances with Angel Gil-Ordonez and the Washington National Cathedral Chorus, also includes music by Nathaniel Dett, William Dawson, and – to close – Johann Sebastian Bach: “Ich habe genug,” unforgettably sung by Kevin Deas.

The podcast mainly samples PostClassical Ensemble’s multi-media production, “Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual” (with a visual track by Peter Bogdanoff), as performed at the Washington National Cathedral. The same production, in various iterations, has been mounted on three other occasions. It travels to Virginia Tech next month as part of a Deas/Horowitz/Gil-Ordonez residency in which “cultural appropriation” will be explored in a separate event. A fifth version, with an expanded presence for Nathaniel Dett, will be seen at the Phillips Collection (DC) on August 22, retitled “The Spiritual in White America.”

Here’s a Listening Guide:

PART ONE:

00:16: “Steal Away” (arr. Burleigh) sung by Kevin Deas (Horowitz, piano)

14:41: “Sometimes I Feel” (arr. Burleigh) sung by Deas (Horowitz, piano)

20:40: “Deep River” (arr. Burleigh) sung by Marian Anderson

25:25: The history of “Deep River,” an obscure upbeat spiritual first slowed down by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1905)

29:37: The Fisk Jubilee Singers’ recording of “Swing Low” (1909)

34:08: The Fisk upbeat “Deep River” (1876), as reconstructed by Gil-Ordonez

37:30: Maud Powell’s recording of the Coleridge-Taylor “Deep River” (1911)

42:00: In sequence, Burleigh’s “Deep River” (SATB), Burleigh’s “Deep River” (TTBB) with “Dvorak” introduction; Dvorak/Fisher “Goin’ Home” (all with Washington National Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez conducting)

57:48: “The elephant in the room”: cultural appropriation

1:07:00: Burleigh sings “Go Down, Moses” (1919); Sir Michael Tippett’s choral arrangement of “Go Down, Moses” (Deas, Gil-Ordonez, Cathedral Choir)

1:15:30: “My Lord, What a Morning” (arr. Burleigh) sung by Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez conducting

PART TWO:

00:00: Nathaniel Dett: “Oh Holy God” (National Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez)

02:55: How classical music in America “stayed white,” penalizing black composers

15:26: Dett’s The Ordering of Moses (conclusion) with James Conlon conducting the Cincinnati Symphony

20:49: Dett: “Listen to the Lambs” sung by Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez conducting

31:08: William Dawson: “There is a Balm in Gilead” with Deas, Cathedral Choir, Gil-Ordonez

37:10: “Where You There” (arr. Burleigh); Bach: “Mache dich” from St. Matthew Passion with Deas, Cathedral Choir, PostClassical Ensemble, Gil-Ordonez conducting

51:28: Bach: “Ich habe genug” (movement 1) with Deas, PCE, Gil-Ordonez

(Igor Leschishin, oboe)

1:01:29: Bach: Air from Third Orchestral Suite with PCE, Gil-Ordonez

Leave a Reply