Charles O’Connell, who commanded “artists and repertoire” for RCA Victor from 1930 to 1944, left a book of reminiscences – The Other Side of the Record (1947) – documenting an astute, querulous intellect and a meddlesome ego. It was often O’Connell who decided what music famous conductors, pianists, and violinists might commercially record.

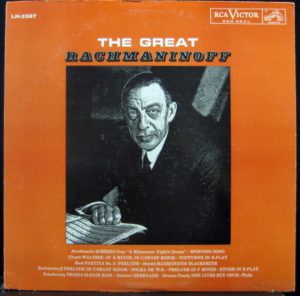

O’Connell admired Sergei Rachmaninoff – yet only recorded Rachmaninoff in two extended solo piano works: Schumann’s Carnaval and Chopin’s B-flat minor Sonata, both classics of the discography for piano. That is: O’Connell failed to record Rachmaninoff’s esteemed readings of Liszt’s Sonata or Beethoven’s Op. 111. Or of the piece Rachmaninoff considered his supreme compositional achievement: the existential Symphonic Dances. Rachmaninoff was known to play the Symphonic Dances, privately, with his friend Vladimir Horowitz in the two-piano version. We know that he wished to record the Symphonic Dances as a conductor. O’Connell had thrice recorded Rachmaninoff memorably conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in his own music. But O’Connell lacked enthusiasm for the Symphonic Dances and nothing was done.

All this matters greatly because Rachmaninoff refused to allow his live performances to be broadcast or otherwise recorded. Even though he was a master of musical structure, we have no documentation whatsoever of how he shaped the monumental Beethoven and Liszt pieces he famously purveyed. As important: we don’t know what he sounded like in a real hall with a real audience.

The new Marston 3-CD set “Rachmaninoff Plays Symphonic Dances” – the topic of my previous blog – permits a glimpse of this “real” Rachmaninoff: a supreme instrumentalist more emotionally aroused than the one O’Connell managed to capture in sound. Rachmaninoff’s private rendering of his Symphonic Dances, as recorded by Ormandy (probably without the pianist’s knowledge), is an unprecedented opportunity to eavesdrop on Rachmaninoff performing absent the intrusive self-awareness imposed by RCA’s microphones.

This historic release also suggests another impediment to hearing the real Rachmaninoff: Eugene Ormandy himself.

Of the repertoire Rachmaninoff happened to record, only one extended composition embeds the searing nostalgia that was the expressive keynote of this great artist. That is the Piano Concerto No. 3. His 1939-40 recording, with Ormandy, is a dry run. The concerto’s lachrymose intensity is missing.

That it did not have to be is proven by Rachmaninoff’s 1929 recording of a less emotionally fraught composition: the Piano Concerto No. 2. The difference is the conductor, Ormandy’s irreplaceable predecessor in Philadelphia: Leopold Stokowski.

Ormandy’s recorded accompaniments to Rachmaninoff’s First, Second, and Fourth Piano Concertos are merely supportive: they give the soloist nothing to work with. (My pianist friend George Vatchnadze, describing the Rachmaninoff-Ormandy relationship, calls Ormandy a “puppy” and a “servant” — apt adjectives.) Stokowski’s accompaniment to the Second Concerto is unique. The signature lava flow of his magnificent Philadelphia strings is not only memorably ravishing; it is acutely calibrated in dialogue with the composer/pianist. It is not for nothing that Rachmaninoff called Stokowski’s Philadelphia Orchestra the greatest orchestra that had ever existed.

If you want to hear what I’m talking about, listen first to the passage from the First Concerto that Vladimir Horowitz once identified as the only instance of RCA adequately conveying Rachmaninoff’s art. This is the piano solo beginning at 12:52 here. And observe how the intrusion of Ormandy’s generic accompaniment cancels the abandon of Rachmaninoff’s playing, with its untethered rubatos and magically layered dynamics.

Now Stokowski – try the coda to the first movement of the Second Concerto, beginning at 8:45 here. You’ll hear pianist and conductor immersed in an inspired dialogue: two exemplary instruments of musical expression – Stokowski’s orchestra and Rachmaninoff’s Steinway – feed one another.

It is hardly surprising that once Ormandy took over, Stokowski did not guest-conduct in Philadelphia for more than two decades. Or that Stokowski, when passing through Philadelphia by train, would invariably lower the window shade.

How is it possible that Eugene Ormandy could have succeeded Leopold Stokowski? Both O’Connell and Arthur Judson, classical music’s supreme powerbroker, played decisive roles (O’Connell, in his book, testifies that Ormandy looked upon Judson “as on a father”). This choice — coinciding with refugee conductors of world stature looking for work in the US (Kleiber, Klemperer, etc.) — is one of the most parochial blunders in the institutional history of classical music in America. It bears comparison with the Met’s decision to replace Artur Bodanzky with Erich Leinsdorf in 1939; Leinsdorf, too, was a refugee — but no Kleiber or Klemperer. Two decades later, RCA inflicted Leinsdorf on the Boston Symphony; the resulting recordings are today forgotten.

And how is it possible that Rachmaninoff chose to record with Ormandy? According to O’Connell, “he preferred Ormandy to anyone, though he collaborated successfully and in the most friendly fashion with Stokowski.”

But O’Connell held Ormandy in exaggerated esteem. And I read in Richard Taruskin’s copious note for the new Marston release that Rachmaninoff, his longtime loyalty to Philadelphia notwithstanding, didn’t care for Ormandy’s reading of the Symphonic Dances — his preferred conductor for that work (other than himself) being Dmitri Mitopoulos. The Marston set includes a scorching New York Philharmonic Symphonic Dances led by Mitropoulos in live performance in 1942.

Another annotation for the new Marston release, by the producers, reports that Rachmaninoff’s preferred interpreters included Stokowski, Mitropoulos, and Willem Mengelberg – an informative list. These were sui generis conductors who never played by the rules. And, however constrained he may have been in the presence of Charles O’Connell and Eugene Ormandy – neither did Sergei Rachmaninoff.

PS: In an email exchange with Gregor Benko, the longtime Rachmaninoff authority who co-produced “Rachmaninoff Plays Symphonic Dances,” I learned the following:

“O’Connell tried to kill two birds with one stone, thinking he would please Rachmaninoff in keeping his promise for Victor to record Symphonic Dances, and satisfying his annual contractual commitment to Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony, by having Stock make the recording. He hadn’t realized how much this would displease Rachmaninoff, or how much Rachmaninoff wanted to conduct the recording himself. As happens so regularly at record companies, this seemingly minor personality kertuffle resulted in total failure, and no one recorded the Dances. O’Connell claimed that Rachmaninoff forgave him later, but we believe that is not true.

“As for plans for recording the Symphonic Dances with Vladimir Horowitz [in the two-piano version]: talk of this has been much exaggerated, based on wishful thinking. Horowitz and Rachmaninoff played it together privately in California, unknown date but sometime after their first two piano partying there in June, 1942. Rachmaninoff was already ill and his circle was very worried. He tried to keep up a good face, and went with Horowitz to see Bambi at the Disney studios. On July 17 & 18 Rachmaninoff played in the Hollywood Bowl and he was bent over. Lumbago, it was explained, but it was probably acute pain. In July Steinway stopped making pianos as the war really began affecting music. A few weeks later his cancer was diagnosed. It was a struggle just to fulfill contracted engagements for late 1942/early 1943, and plans for the future were on hold. No contracts for new things, no dates set aside for new recordings. Each contracted concert played was a trial, and finally in mid-February he stopped the tour. He died at the end of March. There was no way such a recording could have happened . . . ”

For much more on Arthur Judson and Leopold Stokowski, see my “Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall” (2005). For more on Charles O’Connell, David Sarnoff, the provincial NBC/RCA impact on American musical life, see my once notorious “Understanding Toscanini: How He Became an American-Culture God and Helped Create a New Audience for Old Music “[1987].)

I completely sympathize with your Ormandy contempt, since he never met of piece of music to which he couldn’t smoothen out the originaltiy. But I still don’t understand the reason for the extent of the Leinsdorf animus, which seems to be a theme of yours across multiple books and articles and blogposts – which I suppose is a roundabout way of saying that I’m a huge fan of your work who has gone well out of his way to find your writing.

Whether or not Leinsdorf was an unperceptive or boring conductor, he was clearly misused over and over again, promoted at far too young an age to the very top of the profession, imposed on a major orchestra whose tradition he clearly had little sympathy with. But Leinsdorf could still surprise, particularly in later years when he could do pretty much what he wanted as a guest with orchestras. I don’t think anybody is mistaking him for someone who is worthy of the top of the pantheon, but even if his performances don’t often yield too many new insights, he was a virtuoso of the orchestra who could give a tastefully exciting performance of just about anything that conveys the essential flavor of the piece – all the lines balanced so well that all the lines and harmonies and instrumental colors are audible. I’m too young to have heard him live, but from what I hear on record, it was probably an exaggeration to think of him as a great conductor – and perhaps he was treated as such so in that way I suppose understand the animus, but he was too good to be thought just a mediocrity.

Thanks for this.

Many thanks for your authoritative exploration of circumstances surrounding Rachmaninoff’s recordings, especially for emphasizing that his Victor discs do not adequately document his playing. Just one comment concerning the quoted material from me: It is my colleague, Francis Crociata, who is the Rachmaninoff authority, the material quoted the result of his research, Together we are working on a book about Rachmaninoff, the Third Piano Concerto and its dedicatee, Josef Hofmann.

Olga Samaroff was highly instrumental in getting Ormandy in, writing to the Board advocating for him. The alternative under consideration was Reiner, who Samaroff described as an “Opera Conductor” (kinda like Leinsdorf?)…………………we know what happened when Fritz went off to Chicago and turned it into a great orchestra making wonderful recordings in stellar sound for RCA…………….Ormandy stayed in Philly for a very long time making numerous recordings which often struck me as the “third best version” of whatever it was………….

I can sort of understand why not Reiner, Klemperer, Kleiber. All three were such difficult customers that it’s doubtful they would have lasted in Philadelphia any longer than they did anywhere else. I think the right man to replace Stokowski would have been Sir Thomas Beecham, who was clearly looking to get out of England at that point. Had he been approached, I think he’d have likely said yes. Not to mention, this was right around the same time that Monteux went to San Francisco and Mitropoulos made his American debut which caused a sensation around the country. If quality music making was their top priority they easily could have had it.

Congratulations, Mr. Tucker, for hearing significant qualities in the commercial recordings of Erich Leinsdorf. However, even more are to be heard on concert tapes from Boston and during his subsequent, decades-long association with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Leinsdorf’s programming with the BSO was among the widest in the United States, and as guest conductor it became wider still, building on “want lists” given by orchestras rather than a personal collection of party pieces. Standard repertory in Boston often had a tension, even violence, missing from contemporaneous studio recordings, though it largely disappeared from his live performances in later years, which could have a nerveless automatic-pilot quality that also was characteristic (but rarely commented on) of latter-day Solti in Chicago. Unlike most guests in the second half of the century, Leinsdorf frequently interacted with players harshly and sarcastically. The sharpness that ultimately led BSO musicians to vote him out of their traditional Christmas gift stayed to the end, causing many to undervalue the strengths you’ve heard. Read his books. Listen to broadcast tapes. There’s more about him to be discovered.

Before we go on praising Charles O’Connell too much, let’s not forget that was unscrpulous. B. H. Haggin told me in 1981 that he would swing recording gigs for orchestras that would hire him as a guest conductor. Haggin cited an advertisement for RCA recordings by the Cincinnati Symphony, and in small print those ads plugged an upcoming concert conducted by O’Connell. That story has now been confirmed in Harvey Sachs’s massive new bio of Toscanini — to say nothing of O’Connell’s alcoholism, which was know to the Old Man.

Well,

Having been repulsed by JH’s first screed against the great Eugene Ormandy,

I now feel compelled to respond yet a second time. Rachmaninoff’s admiration for Ormandy

is unequivocal. When Ormandy first accompanied him in his Paganini Variations, it was not necessary

to stop the orchestra once (this was in Minneapolis). Rachmaninoff said that he never believed

that an orchestra could be so prepared as well as alert and that no accompanist ever collaborated with him

that superlatively. Moreover, the Symphonic Dances were written with Ormandy and the Philadelphia in mind.

Frankly, it pains me to have to defend a natural genius such as Ormandy, a musician whom

Horowitz, Stokowski, Rostropovich (in my presence) have lauded to the heavens. Meanwhile this

Mr. Horowitz praises Koussevitsky a notoriously poor score reader, bad accompanist, whose repertoire was effectively narrow. So insecure was the Boston leader that very very few guests were permitted to conduct

“his” orchestra. If Mr. Horowitz’s postulate is that Toscanini and Ormandy were overrated and

were fortuitously advanced by circumstances and zealous brokers, this falls under the

rubric of personal taste and “De gustibus non est disputandum.”

BUT … BUT if he is claiming some omniscient science underpinning his opinions,

this professor would be happy to refute his allegations in open debate. To arbitrarily praise Stokowski

and Koussie (whose wayward taste and tempo in the great Austro-German repertoire must be heard to be believed) while damning Toscanini and Ormandy (why? because he is “journalistically” able?!)

is not scholarship, but BIAS only.

Having further reflected upon these issues, I feel an addendum is in order.

Maestro Ormandy, WHOM I HEARD LIVE (Mr. Horowitz apparently disdains the importance of this

necessary-to-judge experience) introduced me to great compositions such as Shostakovich 6th, Bruckner 7th

and Gliere 3rd. Imagine a 17-21 year old already in love with serious music having his horizons expanded

in this manner. I remember being up in the Family Circle or Amphitheater with the music

and the WOW factor of listening and learning something TOTALLY NEW and knowing that

as Vincent Persichetti said of Ormandy: “This is the best possible way it could go!”

As an obligatory correlative to the above, I would mention Szell and Bernstein, two conductors

who, I feel, are extremely overrated. Szell because of his percussive, overly driven tempi and rhythms,

devoid of color interpretations (as if treble existed only and NO BASS). Bernstein for his

sloppy ensemble and overall executions, wayward, self-indulgent tempi. And worst of all, egocentrically

having the music point to him and not the composer. The last never a fault of either Toscanini or Ormandy!!

However, notwithstanding my antipathy for Szell and Bernstein, I would never question why they rose as

they did or attribute their success to extra-musical circumstances.

Dr. Joseph A. DiLuzio

By the way, if the author admires Charles O’Connell, he should then reread The Other Side of the Record.

His portrait and analysis of Ormandy, while critical of some of his personality quirks, is

unmistakably laudatory even glowing. It was Maestro O who taught him “the little [he} knew about conducting.”

O’Connell did of course conduct a bit as well as record.

Conversely, his chapter on Toscanini is wholly negative.

This by way of OBJECITIVITY. A diminishing commodity judging by recent political events.

Dr. Joseph A. DiLuzio