The Bernstein Centenary celebration at the Brevard Music Festival last month was multi-faceted. I was invited to explore the Bernstein story for a week with Brevard’s exceptional high school orchestra (the festival also hosts college and professional ensembles). The result was the multi-media “Bernstein the Educator” program that I described in my previous blog.

I was also asked to lecture on “Bernstein and Social Justice.” This proved a lot more interesting (and timely) than I had anticipated.

After a few hours’ homework I realized that my topic would be the furious backlash Bernstein endured as a consequence of embracing political and humanitarian causes on the left. His activities became an insane obsession of J. Edgar Hoover. The resulting FBI file of some 800 pages included at least one allegation that Bernstein was a Soviet agent. There was also a trail of dirty tricks, including phony letters delivered to the Bernstein home. In the midst of it all, Bernstein was denied a passport by the US State Department. Two decades after that, he turned up on the Nixon/Haldeman tapes, and on Nixon’s enemies’ list (the antipathy was mutual).

Bernstein’s elder daughter Jamie, in the indispensable memoir just published by HarperCollins (the most vivid and affecting portrait of Leonard Bernstein I’ve ever encountered), cites as a peak Bernstein moment the Beethoven Ninth he led in Berlin when the wall came down in 1989; conducting instrumentalists from two continents, he changed Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” to celebrate “Freiheit” (freedom) rather than “Freude.”

Certainly social justice was a Bernstein leitmotif. Another famous Bernstein performance was of Haydn’s Mass in Time of War at the Washington National Cathedral – an anti-war protest timed to coincide with the Nixon inaugural concert across town. And it’s well-known that his early Broadway work was politically tinged – that On the Town was the first musical to cast a Japanese-American (Sono Osato) as an “all-American girl”; that West Side Story was a compassionate response to gang warfare; that the auto-da-fe in Candide lampooned the Red Scare.

This activity was rooted in the company Bernstein kept as a young musician. His close friends included Marc Blitzstein, arguably America’s foremost political composer, and a member of the Communist Party. Bernstein’s mentor Aaron Copland, as is now increasingly well-known, migrated far to the left in the thirties, addressing a Communist picnic in Minnesota and composing a prize-winning workers’ song espousing revolution.

When his passport was held up in 1953, Bernstein feared being asked under oath if he knew any Communists. His response was an excruciating seven-page affidavit, the whole of which is reprinted in The Leonard Bernstein Letters (2013). He testified:

“Although I have never, to my knowledge, been accused of being a member of the Communist Part, I wish to take advantage of this opportunity to affirm under oath that I am not now nor at any time have ever been a member of the Communist Party. . . I wish to state generally as to all the organizations involved that my connection, if any, with them has been of a most casual and nebulous character. . . . Needless to say I never knew their real character as they were later denominated by the Attorney General of the United States.”

The most chilling sentence is a mea culpa: “I did not possess the requisite suspicion and caution to probe the devious and subversive objectives of those by whom I and too many others were innocently exploited.” Bernstein’s associate Jerome Robbins notoriously named names when subpoenaed in 1953. Bernstein himself was never called.

As for the Nixon tapes: When Bernstein conducted the premiere of his Mass to inaugurate the Kennedy Center in 1971, the FBI surmised “plans of antiwar elements to embarrass the United States Government.” A memo described “a plot by Leonard Bernstein, conductor and composer, to embarrass the President and other Government officials through an antiwar and anti-Government musical composition.” The year before, a Nixon memorandum to Haldeman opined: “As you, of course, know those who are on the modern art and music kick are 95 percent against us anyway. I refer to the recent addicts of Leonard Bernstein and the whole New York crowd. When I compare the horrible monstrosity of Lincoln Center with the Academy of Music in Philadelphia I realize how decadent the modern art and architecture have become. His is what the Kennedy-Shriver crowd believed in and they had every right to encourage this kind of stuff when they were in. But I have no intention whatever of continuing to encourage it now.’’

This fascinating document isn’t paranoid – “95 percent” sounds about right. And I happen to agree with Nixon about the Academy of Music vs. Lincoln Center. But sample this, from Jamie Bernstein’s Famous Father Girl: “On Nixon’s tapes, the president’s voice can be heard reacting to H.R. Haldeman’s description of Bernstein at the curtain call of Mass, kissing the male members of the cast: ‘Absolutely sickening.’ But Daddy was rather proud to have been referred to by President Nixon as ‘a son of a bitch.’”

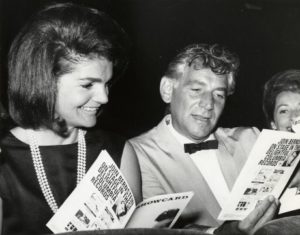

The elephant in the room, as many readers of this blog will remember, is “radical chic” – the 1970 Black Panther fundraiser at the Bernstein’s Park Avenue apartment. Its hostile misrepresentations in the New York Times and New York Magazine long defined (and lampooned) “Bernstein and social justice.” Charlotte Curtis, the Times’ editor “for women’s and family/style news,” turned up uninvited, as did the late Tom Wolfe. Curtis’s reportage in the Times confrontationally construed a titillating entertainment: “Leonard Bernstein and a Black Panther leader argued the merits of the Black Panther Party’s philosophy before nearly 90 guests at a cocktail party last night in the Bernsteins’ elegant Park Avenue duplex.“

A subsequent Times editorial (!) read in part: “Emergence of the Black Panthers as the romanticized darlings of the politico-cultural jet set is an affront to the majority of . . . those blacks and whites seriously working for complete equality and social justice. It mocked the memory of Martin Luther King, Jr.”

And here’s a tasty morsel from Wolf’s “Radical Chic”:

“Felicia is remarkable. She is beautiful, with that rare burnished beauty that lasts through the years. Her hair is pale blond and set just so. She has a voice that is ‘theatrical,’ to use a term from her youth. She greets the Black panthers with the same blend of the wrist, the same tilt of the head, the same perfect Mary Astor voice with which she greets people like Jason, Adolph, Betty, Gian Carlo, Schuyler, and Goddard . . .

“The very idea of them, these real revolutionaries, who actually put their lives on the line, runs through Lenny’s duplex like a rogue hormone. Everyone casts a glance, or stares, or tries a smile, and then sizes up the house for the somehow delicious counterpoint . . . Deny it if you want to! but one does end up making such sweet furtive comparisons in this season of Radical Chic . . . “

As Jamie Bernstein writes: Felicia Bernstein, through her work with the ACLU, had “agreed to organize and host a fund-raising event to assist the families of twenty-one men in the Black Panther Party who were in jail, with unfairly inflated bail amounts, awaiting trial for what turned out to be trumped-up accusations involving absurd bomb plots around New York City. My mother’s dual purpose was to raise money for a legal defense fund and to help the men’s families stay fed and sheltered until the trial came around. (And when the trial finally did come around, the judge threw the whole case out for being unsubstantiated and patently ridiculous.).” Nearly $10,000 was raised – a substantial sum in 1970 dollars.

Two years after Felicia Bernstein’s death, her husband was quoted as follows in the New York Times (Oct. 22, 1980):

“I have substantial evidence now available to all that the F.B.I. conspired to foment hatred and violent dissension among blacks, among Jews and between blacks and Jews. My late wife and I were among many foils used for his purse, in the context of a so-called “party” for the Panthers in 1970 which was . . . a civil liberties meeting for which my wife had generously offered our apartment. The ensuing FBI-inspired harassment ranged from floods of hate letters sent to me over what are now clearly fictitious signatures, thin-veiled threats couched in anonymous letters to magazines and newspapers, editorial and reportorial diatribes in The New York Times, attempts to injure my long-standing relationship with the people of the state of Israel, plus innumerable other dirty tricks.”

This testimony is nothing compared to that of Jamie, when she writes:

“It’s likely that to this day, Tom Wolfe may not understand the degree to which his snide little piece of neo-journalism rendered him a veritable stooge for the FBI. J. Edgar Hoover himself may well have shed a tear of gratitude that this callow journalist had done so much of the bureau’s work by discrediting left-wing New York Jewish liberals while simultaneously pitting them against the black activist movement . . . Nor may Wolfe truly comprehend the depth of the damage he wreaked on my family. Maybe not so much on my father, who suffered embarrassment but could immerse himself in his various musical activities . . . No, it was my mother who bore the brunt . . .

“After that year, Mummy grew increasingly dejected and discouraged. . . . Four years later, [she] was diagnosed with cancer. Four years after that, she was dead of the disease, at fifty-six. Even now, my rage and disgust can rise up in me like an old fever – and in those nearly deranged moments, it doesn’t seem like such a stretch to lay Mummy’s precipitous decline, and even demise, at the feet of Mr. Wolfe.”

So all of this, and more, punctuated my Brevard talk. I delivered it twice, the first time at the public library. Brevard in the summer is a community, rather like Asheville down the road, packed with retirees from the northeast. I was initially astonished that my revelations were quietly received by a large and attentive audience. When I asked what was going on, I was informed that nothing I reported was in any way surprising. And that is where we are as a nation today.

Next summer’s Brevard theme will be Aaron Copland. Among the programs I will produce will be “Copland and the Cold War” – which I’ve presented elsewhere on many occasions. In addition to music, we’ll see and hear a re-enactment of Copland’s inept grilling by Joe McCarthy and Roy Cohn. And we’ll all sing “Into the Streets May First!” – Copland’s workers’ song for The New Masses. Copland, too, was closely watched by the FBI (the switchboard operator at Tanglewood was a hilariously ignorant informant). His backlash experience was as richly embroidered as Bernstein’s – as when vigilant Republicans pulled A Lincoln Portrait from the Eisenhower inaugural.

The back story is that Copland began visiting Mexico in the 1930s, and there enviously discovered a nation in which artists and intellectuals powered social change. His own attempt to become a political artist generated a parable of sorts. It ultimately provoked disapproval and mistrust.

In twentieth century America, artists pursued political causes at their peril. Even JFK, speaking in praise of the artist’s vocation, excoriated political art with scant understanding (I recently wrote a blog about this).

What about today? Very likely we shall have occasion to find out.

Leave a Reply