PostClassical Ensemble’s most recent WWFM “PostClassical” radio show is “Copland and the Cold War” – aired last Friday and now archived.

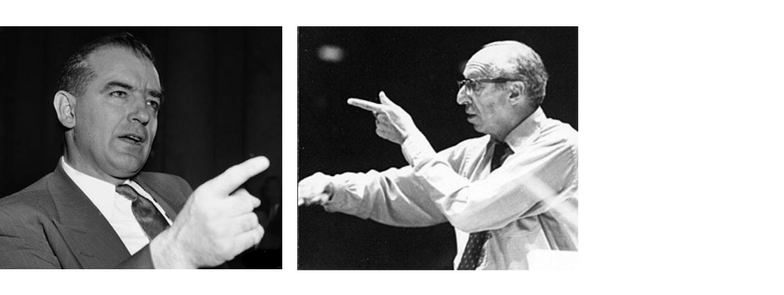

Our two-hour program includes Aaron Copland’s prize-winning New Masses workers’ song “Into the Streets, May First” as well as a re-enactment of Copland’s 1953 grilling by Senator Joseph McCarthy starring myself and Bill McGlaughlin.

And – sampling one of PostClassical Ensemble’s three Naxos DVDs presenting classic 1930s films with newly recorded soundtracks — we audition and discuss Copland’s least-known important score: his music for the classical 1939 documentary The City. Scripted by Lewis Mumford, this film – far better known to film-makers than to musicians – advocates government-built “new towns.” Its images of happy workers remind my wife – a native of Communist Hungary – of the propaganda films she knew as a child.

How far did Copland migrate to the left in the 1930s? Citing Howard Pollack’s biography, I read a couple of 1934 letters in which Copland excitedly described his participation in Communist Party functions among Minnesota farmers:

“It’s one thing to talk revolution . . . but to preach it from the streets out loud — well, I made my speech and now I’ll never be the same. Now when we go to town, there are friendly nobs from sympathizers. Farmers come up and talk as one red to another. One feels very much at home, not at all like a mere summer boarder.”

This Cold War chapter concludes a fascinating and at times chilling three-part compositional odyssey charted by “the dean of American composers.” He began as a high modernist in 1930 with his lean, hard, and dissonant Piano Variations – a breakthrough in American music. Then, spurred by Mexico and the Depression, he turned himself into a populist and composed the ballets by which we know him best. It was during the beginning of this period that he addressed Communist farmers, scored The City, and won a New Masses contest for the best workers’ song.

These political adventures returned to haunt Copland in the fifties – during which decade he was bluntly interrogated by McCarthy and observed by the FBI (we now know that the switchboard agent at Tanglewood Festival was an informant). His Lincoln Portrait was dropped by from the Eisenhower inauguration following protests from Republicans in Congress who marked him as a former fellow traveler or worse. Copland now turned his back on the “new audience” he had once wooed, returning to his modernist roots in a series of non-tonal compositions beginning with the bleak Piano Quartet of 1950.

The result is a veritable American fable – suggesting, among other things, that the US is less hospitable to political artists than was the Mexico of Diego Rivera, from which Copland drew instruction. Copland’s Mexican colleague Carlos Chavez at various times conducted Mexico’s first permanent orchestra, ran the National Conservatory of Music, and directed the National Institute of Fine Arts.

Looking back at his Mexican visits of the 1930s, and doubtless reflecting upon the American prominence and influence of such outsiders as Arturo Toscanini, Copland said: “I was a little envious of the opportunity composers have to serve their country in a musical way. When one has done that, one can compose with real joy. Here in the U.S. A. we composers have no possibility of directing the musical affairs of the nation – on the contrary, I have the impression that more and more we are working in a vacuum.”

At the close of our two-hour WWFM radio show, the three co-hosts had (as usual) different perspectives on the topic at hand. Quoting Roger Sessions’ quip that “Aaron is a better composer than he thinks he is,” I opined that the Piano Variations were Copland’s highest achievement and that his populism was “synthetic.”

PCE Music Director Angel Gil-Ordonez expressed admiration for Copland’s non-tonal valedictory, the Piano Fantasy (1957). Of the populist Copland, the best Angel could do was “He really tried.”

Bill McGlaughlin was aroused by our remarks to passionately defend the entirety of Copland’s oeuvre. From his perspective, Angel and I fail to appreciate the social and political forces impinging on Aaron Copland’s aesthetic vicissitudes — “So you better get over it, Jack.”

The broadcast draws on two PostClassical Ensemble programs: “Copland and the Cold War” (including “Into the Streets,” the McCarthy re-enactment, and Copland piano works in masterly performances by Benjamin Pasternack); and “The City,” presenting the 1939 film with live orchestra. The musical content of both these concerts are preserved on the Naxos recordings we sampled.

Our previous “PostClassical” broadcasts – all archived – are “Are Orchestras Really ‘Better than Ever?'”, a Lou Harrison Centenary celebration, and “Dvorak and Hiawatha.” Coming up next, on 20: “The Most Under-Rated Twentieth Century American Composer” – a tribute to Bernard Herrmann.

COPLAND AND THE COLD WAR

LISTENING GUIDE

PART I – Copland the modernist turns populist

6:30 – Copland the wild man: Piano Variations (1930), performed by Benjamin Pasternack on Naxos

22:00 – Copland speaks at a Communist picnic in Minnesota (1934)

28:00 – “Into the Streets” (1934), Copland’s prize-winning workers’ song for The New Masses

32:00 – Copland becomes a film composer: The City (1939), espousing government-funded “new towns” with happy workers. From PCE’s Naxos DVD.

52:00 – The famous lunch counter scene from The City, in which Copland prefigures Philip Glass

59:00 — “Sunday Traffic” from The City

PART II – Copland the populist returns to modernism

3:00 – Copland in Hollywood: The Red Pony

11:30 – Copland is interrogated by Senator Joseph McCarthy (1953)

18:00 – Giving up on the “new audience” he once courted, Copland composes a non-tonal valedictory: The Piano Fantasy (1957), performed by Benjamin Pasternack on Naxos

In reality, McCarthyism wasn’t as much about the Cold War as it was simply a purge of socially progressive thought in the USA. It also had a special focus on Jews and homosexuals like Copland. We forget that McCarthyism was deeply anti-Semitic.

The Europeans were much more threatened by the Soviet Union than the USA but found no need to purge their societies of progressives or even “communists” — a very wide term that encompassed a large range of people. These purges have left the USA politically crippled to this day.

“The Tenderland” was another of Copland’s socially oriented works and captures some of the most beautiful ideals of traditional American communal sensibility, something now largely lost. Here’s an arrangement of an excerpt from the “The Tenderland” by John Williams that is beautifully done. (Try to ignore the video which puts the whole thing a bit over the top and just focus on the words and music.)

Joe,

Thank you for that program. I did not realize Aaron Copland had published in the _New Masses_, so I did some digging and came up with the following:

• “Workers Sing!” is the name of an article Copland wrote in the June 5, 1934, issue of the _New Masses_, which reviews _Workers’ Song Book_ (1934) by the Workers’ Music League. It ends with an exhortation in keeping with the times: “Those of us who wish to see music play its part in the workers’ struggle for a new world order, owe a vote of thanks to the Composers’ Collective for making an auspicious start in the right direction.” It appears online at: http://www.unz.org/Pub/NewMasses-1934jun05-00028a02

• “Into the Streets May First” is the name of Copland’s own workers’ song, which appeared a few weeks earlier–appropriately, in the May 1, 1934, issue–available online here:

https://www.marxists.org/subject/mayday/music/copland1.JPG

• His song formed part of an article called “Marching With a Song.” As the article documents near its end, “The Worker’s Music League is featuring Aaron Copland’s setting of ‘Into the Streets May First’ this Sunday evening (April 29 [1934]), at its second Annual American Worker’s Music Olympiad. The entire ensemble of 800 voices, comprising the revolutionary worker’s choruses of New York, will participate. The place is City College Auditorium.” It is available online at: https://www.marxists.org/subject/mayday/articles/song.html

Coverage and promotion of workers music fit the _New Masses_ well, a magazine founded primarily by leftist writers and artists who were closely connected to the original John Reed Club of New York City (source also of _Partisan Review_, after many of these people came to feel that the _New Masses_ had evolved into a Party organ). (Alan Wald’s _The New York Intellectuals_ among other books of his covers the magazine well: it’s 30th anniversary edition is due out shortly this year.)

I wonder: would you consider “Into the Streets May First” in any way a “Proletkult” piece?

With the PostClassical Ensemble’s upcoming performance “The Russian Experiment” on 1920s music coming up on October 19, 2017, (http://postclassical.com/russianexperiment/ ) do you have any comment on why Soviet music remained avant-garde music in that first decade of the USSR – or was there any serious attempt in creating “Proletkult” music that paralleled literary efforts (before Stalin insisted on his interpretation on “Socialist Realism”)?

The _New Masses_ ran through a number of managing editors between its founding in 1926 and the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939. When Copland was involved, Granville Hicks was managing editor in 1934, Joseph Freeman before him in 1932–1933, my grandfather Whittaker Chambers in the first half of 1932 (just before he entered the Soviet underground), Walt Carmon 1930–1931, Mike Gold 1927–1930, and Joseph Freeman at the beginning in 1926 (and also later again in 1936–1937). By 1939, Hicks, Freeman, and my grandfather had left the movement altogether.

Of them (all writers), I know that music was very important to my grandfather. Like many Americans, he had the NBC Symphony records with Arturo Toscanini conducting (so I read your book on Toscanini with the old glass records playing). In his memoir _Witness_, my grandfather mentions songs of his childhood and many workers songs (usually in German), including some from Berlin during a visit there in 1923–often with lyrics now hard to find. (I found the same true of some Woody Guthrie songs – like “The Farmer-Labor Train,” with new lyrics based on the tune of “The Wabash Cannonball”–now, try to find the lyrics for his further 1948 take “The Wallace-Taylor Train”!) At TIME magazine, one of their most popular cover stories ever was featured Marian Anderson: Henry Luce broke TIME’s no-byline policy in response to numerous letters and named my grandfather as its author. I don’t know whether the other managing editors paid so much attention to music.

I will keep an eye out for other composers in the _New Masses_ from now on – and look forward to more such performances by the PostClassical Ensemble.

Thank you for this program! – David