Anyone who writes books learns sooner or later that a book has no fixed meaning.

In my case, the discovery came in 1987, with Understanding Toscanini: How He Became an American Culture-God and Helped Create a New Audience for Old Music. The book was reviled and proscribed, extolled and prescribed. This was nothing less than I had expected, having assaulted a high icon. What I had not expected was that so many would read a book different from the one I thought I had written. I recall only one review – among many dozens – that felicitously encapsulated my notion of a social and institutional cultural history using the Toscanini cult as a metaphor for 20th century decline. And that appeared in a scholarly journal far from the mainstream. I also liked the alte Edward Said summarizing, in the New York Times Book Review, that I had composed a “Jeremiad.” But Said proceeded to deplore my failure to consider the cultural critiques of Theodor Adorno. I had written a long book and Said had doubtless read a bound galley with no index – and so (as I pointed out in a letter published by the Book Review) had overlooked my long section on Adorno. (Some years later Said shared with me his puzzlement that he had never again been invited to review for the New York Times.)

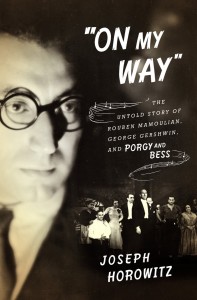

My most recent opus — “On My Way”: The Untold Story of Rouben Mamoulian, George Gershwin, and Porgy and Bess (W.W. Norton) – has received sympathetic notices in publications like the Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and the Times Literary Supplement. I do not complain. Those reviewers enjoyed what they carefully read. They committed no errors of fact or omission. And the meaning of my book to them as is valid as its meaning to me. More than that: I learned things about my book reading how they had read it.

But only this week did I discover a review that more or less precisely coincided with my own reading of On My Way. It appeared in the Bulletin of my alma mater, Swarthmore College, and was written by a faculty member: Andrew Hauze. Hauze’s review concluded:

“While Mamoulian’s direction often took liberties with the text, his changes to the ending of Porgy are downright authorial. By ‘recasting the novella’s dour ending as a redemptive mass finale, Mamoulian nudged Porgy toward a “miracle play” paradigm,’ writes Horowitz. Vital changes were made to the original script in Mamoulian’s hand, including many of the final scene’s most powerful lines (particularly memorable once George Gershwin set them to music). Beyond the brilliant direction of the original production, Mamoulian is, in the end, responsible for the redemptive tone of both play and opera.”

That, I would say, is the spine of my book as I conceived it, more succinctly expressed than I expressed it. What may get lost in the detail of my account is that Mamoulian in later years regarded as his highest achievement his 1926 Rochester staging of Maeterlinck’s miracle play Sister Beatrice – and that (as Hauze’s review stresses) in style, tone, and content this production links directly to Porgy as refashioned by Mamoulian a year later.

Musical theater is typically a collaborative enterprise with many authors. That Rouben Mamoulian, directing Porgy and Bess in 1935, contributed something to the constitution of the most important American opera is itself unsurprising. What I discovered is that Mamoulian’s contribution, stemming from his late revisions to the Dubose and Dorothy Heyward play Porgy, was fundamental – and far from typical. He must in the future be considered an indispensable contributor to the creative vision of Gershwin’s opera, not merely its first director.

Leave a Reply