Watch Hamilton with Lockdown Theatre Club on Tuesday 30 June. Hamilton is available on Disney+. At 8pm everyone presses play and watches together. You can tweet along (#LockdownTheatreClub) or just enjoy the film knowing we’re all part of an audience together.

What is Hamilton? You’re kidding, aren’t you? It’s Hamilton. Filmed by its stage director, Thomas Kail, and with the OG Broadway cast.

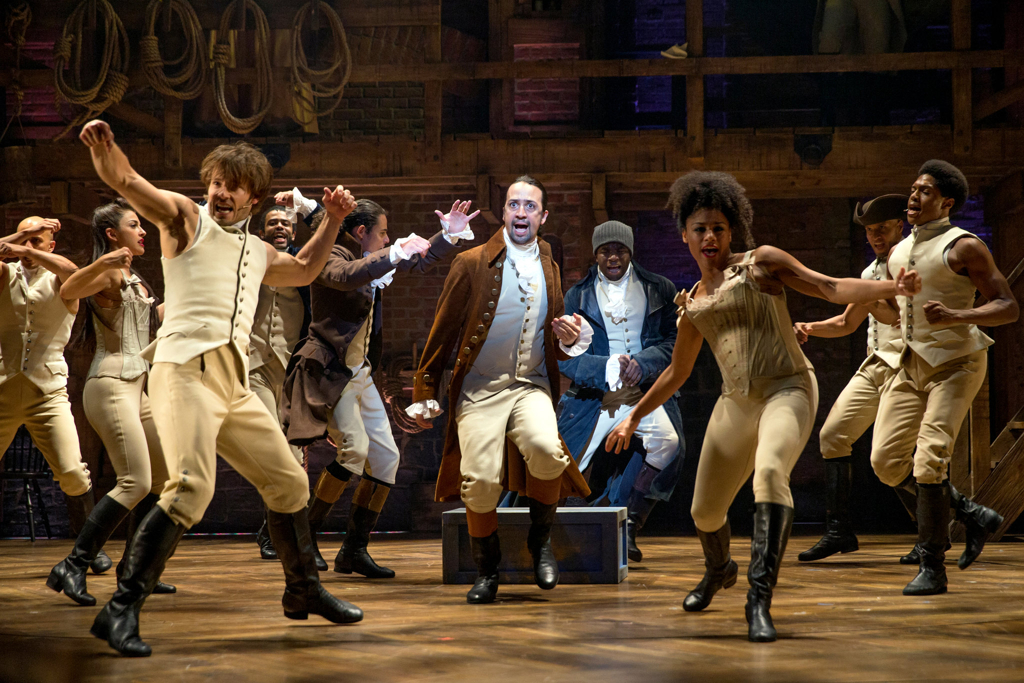

Who else is involved? Presiding genius Lin-Manuel Miranda plays Hamilton and Leslie Odom Jr his tortured frenemy Aaron Burr. Plus Daveed Diggs as Jefferson and Lafayette, Renée Elise Goldsberry as Angelica and Jonathan Groff as George III.

Watch out for? So much – Hamiltonologists leave no detail unannotated. Even Groff’s spittle (‘he’s a moist actor’). It’s the attention paid to props that slays me. I wrote about this modern show’s devotion to throwback paper, and here is a delicious Hamilton prop chronicle.

Frockwatch

Veronica Horwell explores how Hamilton’s costumes speak to then and now.

Look at the extraordinary portraits of Americans that the artist John Singleton Copley painted not long before the 1776 Revolution, and besides the knockout candour of the faces what impacts is the plainness and freedom of their clothes.

True, by then English gentlemen and their town tailors were perfecting a country style far simpler and easier than court or city wear, which after the French Revolution was adopted across Europe as the proto-modern business suit. But the colonials-who-didn’t-wannabe-that are way ahead. They’ve already all moved on to a three-piece, coat, waistcoat and knee-breeches in a plain-coloured wool, or a sportier solid-colour coat over waistcoat and narrow-line breeches in buff natural wool. If they’re uniformed, military fanciness is stripped back to contrasting coat facings, many plain pewter buttons. Some of Copley’s men are (restrainedly) bewigged but notables such as Paul Revere pose in their natural hair, moreover in shirt-sleeves. Very few of his women puff their coiffure, let alone powder it, ewwww, and they’ve almost all agreed that the only wear is a simple gown with a tailored bodice and no-fuss skirt in super-quality plain slipper satin or taffeta, as easy as silk gets and far too sexy at the décolletage to need much adornment. They’ve all taken something off the ensemble to declutter the look before posing. Visible linen for both sexes is superior quality too, with minimal frouf. The outfits are cool, relaxed for their era, not even Anglo business-wear but very nearly modern sportswear (those dresses are early Donna Karan NY).

The designer Paul Tazewell, who had worked with Lin-Manuel Miranda and co back on In The Heights, when commissioned for Hamilton did what he always does for period assignments and looked online at every relevant portrait, citing those of Revolutionary leaders by John Trumbull, the artist name-checked in a Miranda lyric. He also was inspired by Alexander McQueen’s principle that costume IS character, and Kehinde Wiley’s wicked parodies of famous portraits with people of colour wearing so-recognisable garbs.

But Copley’s Americans in their practically-actionwear come closest to what he achieved onstage for Hamilton. He incorporated the period equivalent of some modern details actors wore to first rehearsals (a ‘thrum’ or Monmouth knitted cap, very much like a ski-cap), and established at the Public Theatre readings the rules the show design kept afterwards of modernity from the neck up, in make-up and hair. No wigs, darling. Well, just the one, made of yak hair for King George, whose insanely over-the-top robes and crown (the London crown is glitzier, because we know here just how far royal bling can go) were stolen direct from several portraits of the monarch in regalia full beyond absurdity – a thousand ermines must’ve died to provide their linings. (The show fur is fake.) Doing King G’s historical costume right just proves how wrong he was.

As the excellent Bernadette Banner points out, the Hamilton costume silhouettes, shortening and narrowing over the 30-year timespan of the story, remind you this is history, this really happened, more or less. They’re often achieved by non-period Broadway tailoring techniques, such as a diamond-shaped gusset inserted into the armpit of those wonderful coats, so that when Miranda flings up his arm in the show’s poster gesture of rebellion and triumph, his shoulders don’t scrunch into a heap of padding and seams. There are modern textile aids too, the two per cent of forgiving stretch woven into waistcoat and breeches (the show’s basic tracksuits over which eight dressers add the quick changes), or super-duper-stretch for leggings and side-panels of otherwise correct-cut period stays for the multi-purpose women of the cast.

But the visual reward of Tazewell’s work is the correspondences between then and now. You instinctively recognise the cross-over between bodywarmer and short waistcoat – a vest was meant as a bodywarmer, and if visible as déshabillé showed off its wearer’s arm muscles as it does the dancers’. The soft, low buckled shoes and especially the riding boots were the trainers and hi-tops of then, cobbled for mobility for these always going-somewhere Americans. A little disciplined froth breaks forth at neck and wrist, but only as much we might add now as a scarf to hoodie, polo, T-shirt and sweatpants; the few, strong, simple, touches on an outfit detailed after Copley – contrast reveres or ribbon sash – look very much like the graphics printed on our athleisure gear. (A Hamilton T-shirt abridges costume history, then to now on your back,) When the cast lines up in its formations, it looks like a crack national athletics team in a uniform for movement far better designed than we ever see at the Olympics.

Tazewell sewed jokes too. Miranda wanted his sea-green suit not because that was indeed a bold late-18th century revolutionary fashion shade but because it was the colour of money (dollar bills, although the first printed greenbacks only date from 1862) and Hamilton was Treasury Secretary. Thomas Jefferson, most grounded of the Founders, was intended to be dressed in an 18th-century cool bark brown, but Daveed Diggs played him as a Constitutional rock star, so Tazewell upgraded his look to the purple and pink worn by Jimi Hendrix and Prince.

Veronica Horwell writes for publications including the Guardian and Dance Gazette.

Indeed, in the late 18th century people learned that properly toned-down attire was important for slave owners proclaiming democracy. And today we’ve learned that if you rhythmize bullshit, people will believe anything. Sorry to be so cynical.

An article that analyzes the serious problems with “Hamilton” by Ed Morales, a journalist and lecturer at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race and the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY.

https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/05/opinions/hamilton-movie-mixed-messages-black-lives-matter-morales/index.html?fbclid=IwAR3ao6cdshVlR7CTn6X_GD7VgXz70ehB2c_xqXmf9XmrtXbx8_Wg3Y72B0c

Blimey. A tour de force! Hugely enjoyable. Slight demur on whether a period raised fist would have produced a scrunched up padded look – given the distressing lack of power dressing round 18th century shoulders – but ready to defer to expert knowledge…

Thanks!

Know what you mean about the underpowered pre-17late90s shoulder: a bottle slope approach to body outline — the Hamilton coats have been, shall we say, pumped up a bit? (Maybe just by the physiques of the fab guys wearing them.) But thrust your Revolutionary fist high in an armhole that hasn’t had extra acreage, such as a gusset, inserted in the arm-pit, and the sleeve-body seam piles on to the shoulder itself. Would ruin that poster…