Watch The Go-Between with Lockdown Theatre Club on Tuesday 16 June. The Go-Between is available on Amazon Prime, Sky and other services. At 8pm everyone presses play and watches together. You can tweet along (#LockdownTheatreClub) or just enjoy the film knowing we’re all part of an audience together.

What is The Go-Between? The third of the films Harold Pinter wrote for director Joseph Losey, The Go-Between (1971) follows The Servant and The Accident. All three explore desire and the dead hand of the British class system – The Go-Between, based on LP Hartley’s novel, sees a young boy become enmeshed in an affair between an upper-class lady and a local farmer during the long hot summer of 1900.

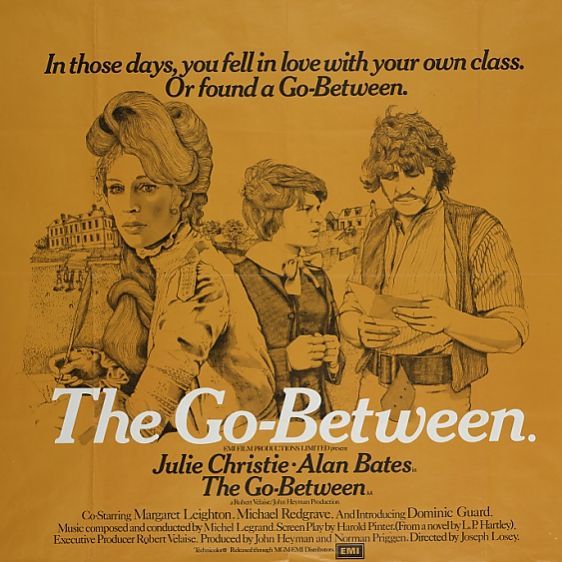

Who else is involved? A superb cast includes Julie Christie and Alan Bates as the lovers, alongside Margaret Leighton, Michael Gough and Edward Fox. Dominic Guard plays the young boy and Michael Redgrave his older self, still haunted by the events of that long-ago summer.

Listen out for? The evocative score by Michel Legrand (Les Parapluies de Cherbourg), which almost ended his working relationship with Joseph Losey (read the full story here).

‘The ferocity of the line’: Lia Williams on working with Harold Pinter

The actor and director Lia Williams introduces The Go-Between and describes what she learned from working with Pinter – lessons in ferocity, economy and an uncluttered dressing room.

Lia Williams has appeared in Pinter plays including Old Times, The Hothouse, The Homecoming and Celebration/The Room. She directed Ashes to Ashes for the Pinter at the Pinter season in London in 2018.

They filmed things differently then

Veronica Horwell on period(ish) costume and auditioning country houses – the design of The Go-Between.

LP Hartley had, like his character Leo, stayed at a Norfolk great house, Bradenham Hall, in a summer of the 1900s, and Joe Losey considered shooting there. But he and art director Carmen Dillon auditioned around 20 houses in the right countryside to match the novel, before eventually choosing Melton Constable Hall, a large 17th-century building in failing condition. (Even worse now; parts in danger of falling down.) So there were no objections to painting and papering rooms in fawn-brown-greys, changing window glass to achieve the inside-outside photography crucial to the look. And spraying the patchy lawns green.

The Hall’s finest rooms weren’t used; what really attracted Losey was a substantial wooden staircase with turned balusters, and further service stairs off it, plus opaque-windowed screens concealing servant areas. The Go-Between is the last of Losey’s staircase trilogy: The Servant, designed by his favourite art director Richard Macdonald, and Accident, also the work of Dillon, with its more subtle attention to front halls as well as staircases. Most of Melton Comstable’s wooden floors, including the stairs, were left uncarpeted for soundtrack clatter, and look anachronistic. Luxurious life in 1900 was seldom bareboarded.

Dillon was old enough to recall actual pre-1914 interiors, if less luxurious, had skivvied in British low-budgets through the 1930s, joined Roger Furse on Olivier’s 1945 Henry V, and won her Oscar for Olivier’s 1948 Hamlet, a stylised looming gloom also with multiple staircases (stone, faked in plaster). She took what work was on offer, crashing between Olivier’s Richard III and Carry On Constable. She thought her forte was realism, willing to interpret that as scouting for the right walls, working over their finish (look at farmer Ted’s kitchen plaster carefully abraded) and dressing a room with real furniture and objects – there were still plentiful sources in the 1960s and 70s for the enamel soap-dish with draining holes which is more a Ted-personality prop than his fatal shotgun. His glass milk-jug, filled by dipper from the churn, says something unexpected about him too.

Although Dillon claimed the Maudsley family lived in ‘rather elaborate vulgarity’, the Hall is by our period movie standards understuffed, the well-pressed white linen tablecloths show empty between the silver (Pinter mentions silver teapots in the script –‘ the glow of silver’) and the porcelain tea-set. And 1971 is a bit early for the posh house full-staffed kitchen porn that became a dominant genre during the decade; just a glimpse of Leo being treated kindly at a mixing bowl.

The locations have now become the past as a foreign country themselves. The buildings of the defunct small dairy farm on a nearby estate used for Ted’s Black Farm, like the overgrown walled gardens and ruining outhouses of the Hall, belong to the rural landscape of half a century ago – the garden staff long gone but big agribiz yet to arrive and raze the hedges for cereal prairies. Losey had a small wheatfield planted so Ted could harvest it with old heavy machinery he discovered. They did filming schedules differently then.

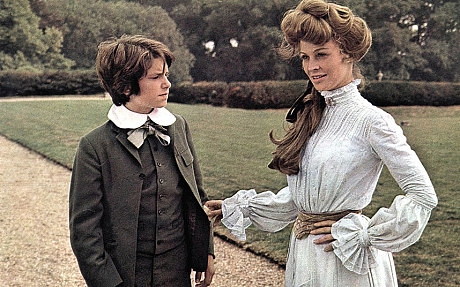

Costume designer John Furniss had to keep close to the book for two essential outfits; Leo’s Norfolk jacket, too hot, too middling-class, and the ready-made Lincoln green suit, of what looks to be a wool blend and still with a waistcoat, Marion buys him for coolth. Its cut, the childish wide short pants, was taken direct from the dust jacket illustration on the original 1953 edition. Poor Leo! Only at the cricket match where he saves the day does he get to wear adult long flannel trousers, albeit with school blazer. (The gentry’s assembled striped blazers are their own bunting.) And Poor Ted, too, his cord waistcoat and unconvincing knot of neckerchief (check the Museum of English Rural Life for the real styles), let alone Alan Bates’ post-Woodstock hair make him such a period piece, and that period is 1969. He wears his swimsuit like a tank top.

You have to get past the hair of Julie Christie and Margaret Leighton too. At the turn of the 60s-70s there was a fashion for long hair set on beer-can sized rollers under a dryer, then pinned up and hard-lacquered into puffed Japanese/Edwardian dos – take a look at Princess Anne’s engagement pix – that’s how they’re styled, especially Leighton. The hats aren’t Edwardian straw braids, either, the men’s boaters insubstantial and the women’s brims in the floppier baku straws fashionable in the 70s. Wealthy Edwardian women would’ve sniffed at the low definition of the artificial flowers. Leighton is given researched details, like a clip to hold up her skirt walking in the garden. Christie doesn’t look or move as if corsetted beneath her white lingerie blouses and dresses, which are a petticoat or two short of 1900 respectability; similar vintage pieces, especially underwear such as camisoles, had been fashionable daywear from the mid-60s, and semi-copies of antique blouses were worn with the new maxi-skirts from 1967. Christie’s costumes are painstaking replicas of the real pin-tucked articles, with many inserts of likely vintage embroidery and lace, yet she wears them as if they were the contemporary cosplay versions. That makes the moment she reacts to her lack of pockets (accurate for 1900) in which to conceal her assignation letter such a surprise. Oh, this is meant to be then then.

Veronica Horwell writes for publications including the Guardian and Dance Gazette.

Leave a Reply