Watch Girlhood with Lockdown Theatre Club on Tuesday 9 June. Girlhood is available to rent on Prime, Sky and other platforms. At 8pm everyone presses play and watches together. You can tweet along (#LockdownTheatreClub) or just enjoy the film knowing we’re all part of an audience together.

What is Girlhood? Before Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Céline Sciamma directed Girlhood (Bande de filles), set in the Paris. Marieme joins a girl gang in the Paris banlieues, discovering a liberating outlet for her bravado, but also experiencing the pressures that attempt to quash her spirit.

Who else is involved? Sciamma cast non-professionals as Marieme and her fellow gang members: Karidja Touré (Marieme), Assa Sylla (Lady), Lindsay Karamoh (Adiatou) and Marietou Touré (Fily). It’s still rare for French films to focus on black characters: ‘[Drama] schools were empty, the theatre and acting classes were nearly all white,’ Sciamma said.

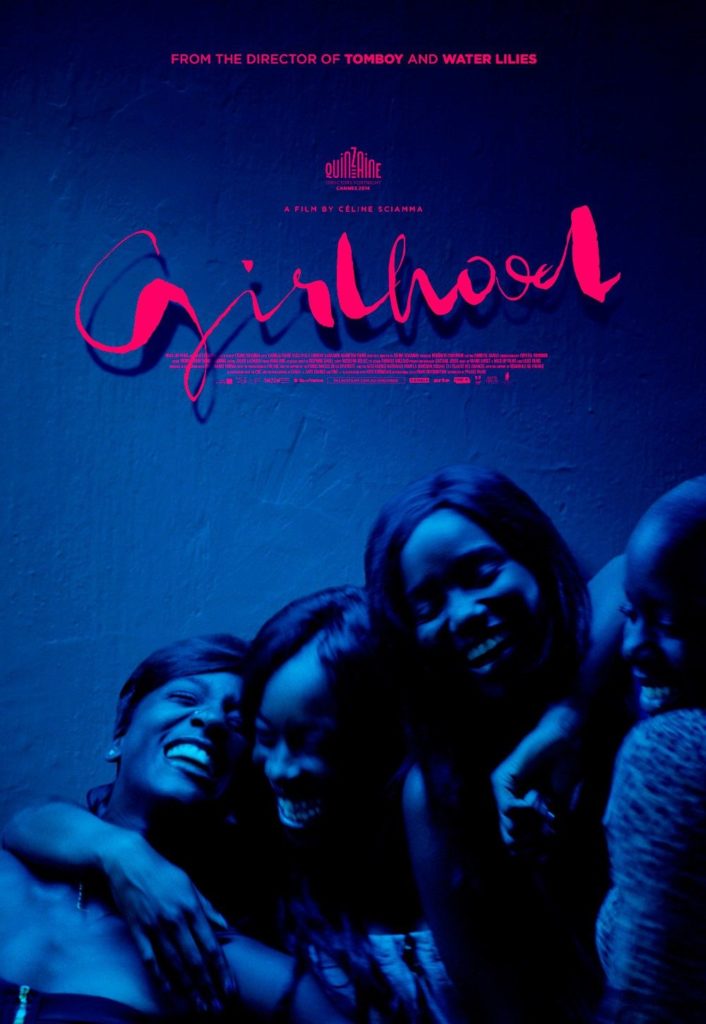

Watch out for? The scene where the women dance to Rihanna’s Diamonds in a hotel, bathed in blue light.

Trailer

Sharing the loneliness

Céline Sciamma on Girlhood

I wanted to make a movie about friendship and also about anger. I wanted it to have a social background that was more anchored. … I wanted to talk about the empowerment of the group and the joy of the group. I wanted it to be kind of epic with long scenes.

For years, I was struck by the lack of black characters on screen — in France, but even in Europe. I came up with this idea for a coming-of-age story with this very contemporary character: the classic, romantic heroine but from today.

This film is committed to being colourful, to cinemascope, to having frames that are composed, to the music. The fact that it believes so much in cinema, that it uses all the tools of cinema, actually makes it joyful. As the character refuses the destiny that is set for her, the film also refuses the form that is set, that it’s supposed to have. And I think that’s a promise. I think that’s something that lifts you up.

The hotel scene, the Rihanna scene, is the key scene for me. It was written for the song. It was the scene I most wanted to shoot. It’s about the birth of a friendship — how a friendship actually rises. It’s all about that girl watching the others being beautiful together and synchronized — finally stepping in and being at the centre of something, feeling iconic and beautiful. [She] suddenly gets a voice and [is] stepping from fake diva to kids jumping on beds. They have a voice when they’re together.

I tried to think of the plot, the narrative, and the links between the characters as a choreography. Sometimes, it’s literally a choreography, because they’re dancing. Sometimes, the choreography is about the camera.

Cinema is the only place, the only art ever, where you share somebody’s loneliness. If you read a novel, you can be in the mind of somebody. But you’re in the mind: that’s not the same. You share the loneliness [in cinema]. Sharing the loneliness with somebody: you can’t get closer to that.

Edited from an interview with Sciamma by Alex Heeney (Seventh Row)

Sensory overload

Emma Wilson on dancing to Diamonds

Sciamma as writer and director is peculiarly attentive to sensory detail, to what things feel like. This attention can be felt through her collaborative work with director of photography Crystel Fournier. Together, they create controlled visual environments, bathed in cool colors, blue, turquoise, green and a nauseous yellow. There is here a commitment to a filmic synaesthesia, a sort of sensory overload that surpasses aestheticism to carry intense feeling, to channel rapture, sensory, hurt.

The scene of most intense intoxication (for Marieme as well as the audience) is the gang-girl dance to Rihanna’s Diamonds. The girls are in a rented hotel room, a safe space of comfort and luxury where, like children playing an imaginary game, they take bubble baths, eat pizza, and dress up in stolen frocks.

Their hotel-room dance sequence is bathed in lush blue light. Girlhood’s images are on the side of beauty, the ethereal. They are silvered, ‘the blue of vivid dreams and cigarette smoke.” This is the film at its most aestheticised. The film cuts to Vic in awe, smiling, moving almost imperceptibly to the music. The camera comes in closer and closer to her face as she watches and listens, her skin shining with reflected blue light, her eyes full of pleasure and grief. Then she too dances in the blue circle of light, stepping into this field of bodily sensation, of beauty, of pleasure. This is a film unafraid of launching a sequence that fully realises the energy, glamour and sheen of the bodies being viewed.

Edited from Scenes of Hurt and Rapture: Céline Sciamma’s Girlhood (Film Quarterly)

Leave a Reply