Watch Romeo + Juliet with Lockdown Theatre Club on Tuesday 12 May. Romeo + Juliet is available to rent on Prime. At 8pm everyone presses play and watches together. You can tweet along (#LockdownTheatreClub) or just enjoy the film knowing we’re all part of an audience together.

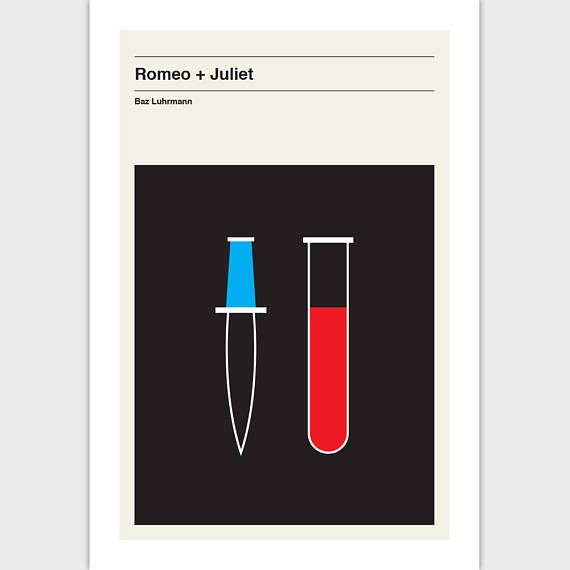

What is Romeo + Juliet? Baz Luhrmann’s audaciously inventive 1996 film reimagines Shakespeare’s tragedy in ‘Verona Beach’ a contemporary Miami-like city, where the Montagues and Capulets are feuding property tycoons. Claire Danes (only 16 when the film was made) and Leonardo DiCaprio play the star-crossed lovers.

Who else is involved? British acting legends: Miriam Margolyes as the nurse and Pete Postlethwaite a herb-nurturing friar. Also Harold Perrineau (Mercutio), John Leguizamo (Tybalt) and a young Paul Rudd as Paris.

Watch out for? Catherine Martin’s design (she is Luhrmann’s partner in life and work) is typically eye-popping. Wonderfully styled, her design is stippled with cheeky references to Shakespeare – like the billboard ad for Propsero Whiskey.

Trailer

The lovers’ element: Hester Lees-Jeffries on Romeo + Juliet

Baz Luhrmann’s film is often discussed in terms of MTV and music videos, and those influences are very clear in the fast editing, the montages, slow motion and high speed sequences, and of course in the soundtrack (RIP Prince).

Whereas Franco Zeffirelli’s film, for all its 1960s fetishisation of youth, had bid for classic status in its finely detailed Renaissance realism, one of the taglines for the Luhrmann film was ‘the classic love story set in our time’, we being my generation and younger, born from the late 1970wards and brought up not just on music videos but on American television, especially gritty police dramas like NYPD Blue and Law and Order, marked by hand-held camera work and street realism (RIP Brian Dennehy), and the glamour and narcissism of Beverly Hills 90210 (the original series). There’s a gesture, too, at the high-school screen musicals of the 1970s and 80s, in the vivid evocation of intense friendships and rivalries, the centrality of music, the certainty of teen rebellion, and really cool cars. Of course many of those features, and those musicals and TV series looked back to Romeo and Juliet itself, via West Side Story.

In introducing Romeo, Luhrmann nods at Zeffirelli’s languorously teasing long-shot as he mixes the familiar televisual device of the conversation in the back of a car with the first glimpses of the lovely Leo. It’s not just that Romeo is teasingly back-lit in gold, however, in contrast to the chilly blue of the limousine, but the switching between different cinematographic aesthetics. The sense of the lovers having their own editing style and their own look (with digitally-heightened colours) continues throughout the film, and their time and place is made in the editing suite. When Romeo and Juliet see each other for the first time, it’s through a fish-tank in a bathroom the likes of which none of us will ever see. The brightly-coloured fish continue the hallucinogenic aesthetic of the party, but they move slowly, dreamily. The mundane space of the bathroom is transformed into a place of magic and beauty, aided by the soundtrack. And here water is introduced as the lovers’ element, a motif which Luhrmann develops throughout the film; it gives them a place, and a space, apart.

When Romeo and Juliet finally meet (not through an aquarium) they share a sonnet, as we all know. On stage, it’s like a sonnet-shaped spotlight: poetry-readers in an Elizabethan audience would get it, would get the intimacy and sexiness of sharing a sonnet, a stanza, literally getting a room… But how to translate this textual intimacy to the stage, let alone to film? Luhrmann uses the vocabulary of film to reinforce the ecstasy of Romeo and Juliet finding each other: they hurtle into a lift, which carries them up and away, and he introduces into that tiny, confined space a glorious shot which tracks around their embracing bodies in an exuberant spiral, which makes the tiny lift seem enormous.

That sense of apartness achieved in the sonnet, and the lift, is revisited in the balcony (or rather pool) scene, where it’s not simply the water itself, but the slow patterns of reflections, clothes, hair, and bubbles that make it so dreamy. True, bringing the lovers together in the pool removes the tension of the distance between them, although perhaps the very overt dynamic of surveillance offsets this a little. But the splash as they fall (yet again) into the pool sounds like a gunshot, and it anticipates the scene of Tybalt’s death.

The final image of the film’s closing montage is that dreamy underwater shot, but the whole aesthetic of the tomb scene recalls the vivid colours, especially the electric blue, of the aquarium. The water makes visual and sensually palpable the craving of these lovers, any lovers, for a space and time apart; it suggests a connection between melancholy Romeo hanging out on the beach, looking out to sea, and the woman who promises him that her bounty is as boundless as the sea, her love as deep. And to show water in motion is a classic assertion of being a film, not a still photograph, and not theatre either. Apart from the ostentatiously ruined beach theatre, scene of Romeo’s sunrise mooching, there’s no residual sense of the stage in Luhrmann’s film at all; it’s coolly and utterly confident in its own medium.

The second time I saw Luhrmann’s Romeo and Juliet in the cinema, when it had been re-released to capitalise on the success of Titanic, the closing scenes were accompanied by sobs from the teenage girls in the row behind. Understandable enough, but what they were wailing wasn’t ‘Romeo, Romeo’, or even ‘Leo, Leo’, but ‘Jack, Jack’. Perhaps they too had been moved by these watery connections…

Hester Lees-Jeffries is a Fellow of St Catharine’s College, Cambridge. She is writing a new introduction for the New Cambridge Shakespeare Romeo and Juliet and in 2018 wrote Starcrossed, a line-by-line daily blog about the play. Follow her @starcrossed2018

Leave a Reply