Watch Les Enfants du Paradis with Lockdown Theatre Club on Tuesday 26 May. Les Enfants du Paradis is available to rent on Prime. At 8pm everyone presses play and watches together. You can tweet along (#LockdownTheatreClub) or just enjoy the film knowing we’re all part of an audience together.

What is Les Enfants du Paradis? Marcel Carné described his film as ‘a tribute to the theatre’. Made in France during the straightened, frightened last years of the war and released in 1945, it is immersed in mid-19th-century Parisian theatre, as an inspired mime and a charismatic stage star are rivals for a uniquely independent woman.

Who else is involved? The poet Jacques Prévert wrote the screenplay, and the film stars Arletty, Jean-Louis Baurrault and Pierre Brasseur.

Watch out for? Maria Casarès, who plays Barrault’s unhappy wife in the film, also starred as Death in Jean Cocteau’s Orphée.

Trailer

Pleasures and sorrows

Veronica Horwell on the creation of Les Enfants du Paradis.

Early in 1943, long-time colleagues director Marcel Carné and poet-scriptwriter Jacques Prévert were in Nice, as life was laxer on the Riviera, where the occupying forces were at that time Italian not German; other Carné colleagues, designer Alexandre Trauner and composer Joseph Kosma, both emigré Jews, were hiding in inland Provencal villages.

On a cafe terrace on the Boulevard des Anglais, Carné and Prévert met actor Jean-Louis Barrault, full of stories about mime artist Deburau, whose pop hero Pierrot had been the sensation of the Théâtre des Funambules in revolutionary 1830s Paris; he was tried for murder after felling a mocking passer-by with a blow of his stick. The escapist past was the only safe space for a movie made under Vichy governance and German censors (Carné and Prévert just had a medieval box-office hit, Les Visiteurs du Soir), and Carné was fascinated by early 19th-century pop drama – the melodramas and spectacles of a century before were entertainments of the people, direct ancestor to cinema.

He went off to research in Paris’s local history Musée de Carnavalet, and scrabble through boxes of old ephemera along Seine quays, returning with images of the many theatres along the ‘Boulevard du Crime’, playbills, illustrated magazines. He, Prévert and Trauner then spent months in a rented house near Nice, oblivious as possible to the war through the creation of a complete world, as big and detailed as a Balzac novel, with real characters – Deburau (renamed Baptiste), Frédérick Lemaître (France’s Edmund Kean, who played the very modern anti-hero Robert Macaire), and the Romantic criminal Lacenaire. All revolved around Garance, pickpocket, stage beauty, and kept woman owned by no man, who was mostly created by, as well as for, Arletty, the attitudinous inspiration of Carné and Prévert. The leads were interchangeable with their characters – angsty, angular Barrault as Baptiste; Pierre Brasseur, a charmer inclined to drink, as Lemaître. The first choice for the sinister Old Clothes Man, a stock villain in 1820s-30s melos, Robert le Vigan, was so notorious a Nazi collaborator he dropped out, and the role went to Pierre Renoir.

Elaborating fantasy

Carné, Prévert and Trauner elaborated their fantasy between them, with Trauner creating paintings, sketches and models of theatre interiors complete right up to cheap seats in the gods (le paradis) and a full-scale stretch of the Boulevard, for craftsmen to build at Nice’s Victorine Studios. Most interiors were to be shot in Paris studios, including Lemaître’s wonderful backstage apartment, a Trauner special; its layout and decor, its complete narrative of a character’s life through made or found props, was echoed in gentlemen’s chambers he later designed for Billy Wilder’s The Apartment and The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.

Money seemed no problem since Carné was offered a big budget through an Italian company. He was never a man to stint expense on or off screen; when Garance’s extravagant tribute bouquets wilted overnight, he ordered twice as many flowers delivered. But supplies were scarce in a France barely getting by. The exteriors were plaster fronts on timber scaffolding, materials so hard to find that production companies employed a man just to extract and straighten nails for re-use, and others to queue perpetually at official bureaus issuing coupons for needed goods. The costumes, designed by the painter Mayo with input from Trauner, tapped caches of luxury textiles once meant for couture; when Garance returns to Paris in splendour in purple velvet with gold braid, the richness registered even in black and white

The real Deburau’s Pierrot costume had been white cotton to take the hard wear of acrobatics, but Baptiste’s in the movie was of silk, which flows and droops around Barrault like melancholy made material, and shines in Mediterranean sun. The real costume challenge was outfitting hundreds of extras, most as Pierrots, for the final carnival, foreground hires likely supplemented by cut-up sheets and tablecloths.

A glowing alternative to grim life

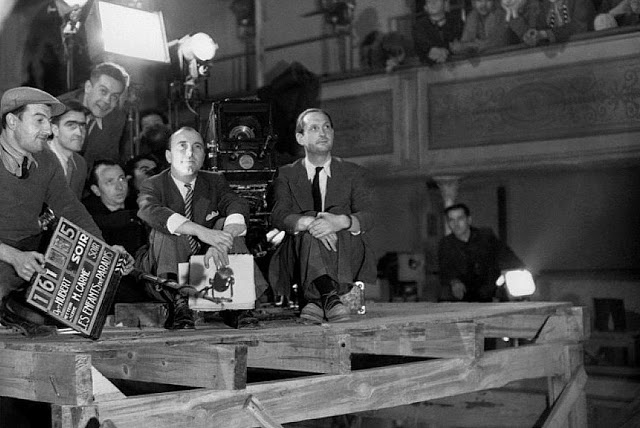

Marcel Carné on set

Though the Boulevard set wasn’t quite finished, shooting began in August 1943, by which time the Allies had landed in Sicily, Mussolini had been deposed and Italian backing withdrawn, while the German authorities were at last paying serious attention to the Riviera. They ordered production stopped, and it was February 1944 before filming, with Pathé having finally been persuaded to finance its completion, returned south. Winter had fritted the plaster and battered the wood of the exteriors. Some were never quite rebuilt, so Carné, Prévert and Trauner dropped scenes, or concocted bridging versions shot in corners. There were electricity outages, a dearth of film stock, a curfew; extras exited to join the accelerating Resistance, and the ever-enigmatic Arletty continued her very public affair with a German officer.

Carné’s reaction was to deliberately extend the slow pace of shooting, up to and beyond the allied D-Day landings in June, when the production was again ordered shut. As occupation ordinances forbade films longer than 90 minutes, the story had been shaped to be shown in two parts (there are hints, including costume designs, of a planned third about the murder trials of Baptiste and Lacenaire), but Carné wanted his whole three-hour film to be the first premiere in a free France, and was in no hurry. The prolonged filming of this simulation in wood and plaster of a theatrical world of lath and canvas absorbed all the energies and attentions of those involved through hectic yet dreamy months, a glowing alternative to grim life. Its post-production dragged through the winter of 1944-45, materially and emotionally the most bitter of the war in France despite, perhaps because of, liberation. Arletty had been tried as a traitor, sentenced to a year in detention, and Carné had to ask for her brief release to dub dialogue. ‘She arrived at the studio in handcuffs with two gendarmes and everyone turned their backs on her, even Brasseur,’ he said. ‘She had to do her first scene with him, very lively and cheeky and gay. And she did.’

The film opened in Paris on 9 March 1945. Everything that had happened in the two years before – betrayal, loyalty, political conflict, the pleasures and sorrows of ordinary people, even the incident where Arletty, with Germans, walked in on Carné taking a hungry Trauner out to a restaurant lunch and got her colleagues away unarrested; it’s all there still onscreen, forever implicit among the tumblers, pratfalls, declamations and applause, Baptiste’s final cry of ‘Garance, Garance’, perhaps meant to be resolved in a sequel, but fortunately never was.

Veronica Horwell writes for publications including the Guardian and Dance Gazette.

Leave a Reply