Watch All About My Mother with Lockdown Theatre Club on Tuesday 5 May. All About My Mother is available to rent on Prime and the BFI Player. At 8pm everyone presses play and watches together. You can tweet along (#LockdownTheatreClub) or just enjoy the film knowing we’re all part of an audience together.

What is All About My Mother (Todo sobre mi madre)?

One of Pedro Almodóvar’s best films, winning the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 2000. Cecilia Roth plays a woman who goes to Madrid after her son is killed in an accident. Searching for his father, she meets a nun, a trans sex worker and a starry actress. It’s a drama about female strength and solidarity and a love letter to classic Hollywood.

Who else is involved?

Marisa Paredes plays the stage star, Huma Rojo, and Penélope Cruz plays the nun Rosa.

Watch out for?

Fittingly for Lockdown Theatre Club, Almodóvar dedicates the film ‘to all actresses who have played actresses. To all women who act. To men who act and become women. To all the people who want to be mothers. To my mother”.

Trailer

‘Funny, selfish and generous’: Samuel Adamson introduces the film

The playwright Samuel Adamson introduces the film (standing beside the film poster in his kitchen). Samuel adapted it for the stage in 2007, with Lesley Manville and Diana Rigg starring at the Old Vic. His plays are published by Faber and Faber, and you can follow him @samuelmcadamson

Decorwatch and frockwatch

Pedro’s bag of bits and pieces: Veronica Horwell on the ‘more is MUCHO more’ décor of All About My Mother.

All About My Mother was the second of the seven Almodóvar movies on which Antxón Gómez has worked as art director or production designer, although Almodóvar confesses, ‘I’m the art director of all my movies. Even though someone else signs off, I really do all the decor.’ The process is slow accretion: the first decision wall colour, then floor, the largest surfaces in the frame. Any sets need to be up a couple of months before shooting, so he can select furniture piece by piece, first casting the couch and its upholstery. then clothing the actress who will lounge on it. Lamps are auditioned, vases tried out – though does Almodóvar ever reject or delete any objects his set decorators truffle out for him? Then, according to Gómez, ‘Pedro loves walking up and down the sets with his bag of bits and pieces, putting them here and there.’

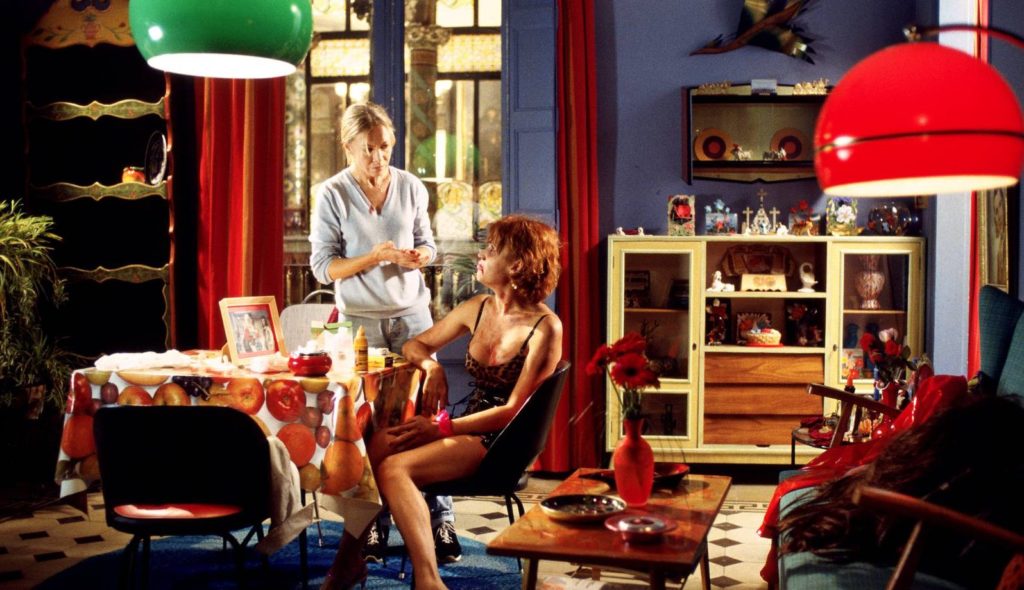

Mother is a little different, though, because so much was filmed in Barcelona, where Gómez had lived since the 1970s; much of its architecture and decor had been created with Almodóvar’s more-is-MUCHO-more aesthetic anyway. The film built on that. Nothing but a roomfull of fake Chagalls was added to the painted dados and stained glass in the apartment in the 1908 Cases Ramos used as the home of Rosa’s parents. Agrado’s wee flat is a hoard of family and religious knick-knackery (although she complains Lola made off with the best of her 70s collection), yet unusually has plain walls. That’s because, through the window and over her balcony, we can see the Art Nouveau flower-mosaic’ed front pillars of the Palau de la Musica Catalana. The Hospital del Mar, Teatre Tivoli, Montjuïc Cemetery, cameo as themselves with just a dab of make-up, a potted plant.

So all the real Almodóvar interior as character and backstory – he’s as good at that as Charles Dickens, every object chosen to contribute to the narrative – was put into the apartment in a slightly battered Nouveau block (to judge from its front hall stucco) that Manuela rents on arrival from Madrid. It’s enormous, but stays relatively empty, marquetry bedhead, shell-plaque chandeliers and lurid glass bottles just edging into view. Open doors and planning mean the camera catches patterned wall-tiles, two different patterned tiled floors, and three exhausting wallpapers with just a slight shift of lens. The geometric wallpaper behind the couch gets most of the action – Gómez called it obsessive, its design ‘simulates two eyes as if it’s observing the spectator’. (In 1999, art directors could either hunt for rolls of forgotten paper horrors in old stockrooms, or screen-print their own design; short-run digital printing to order now makes possible such treats as the walls of Iannuci’s David Copperfield.)

Everything in the place suggests it was there by the late 70s, when Manuela was young in the city, and has been waiting lifeless since then; she adds little of herself during her temporary return – a bright new bowl or two to eat from, a painting hung on that staring-eye wall. But she’s in residence, not staying. Nothing accretes. Bold artistic choice for Almodóvar, how he did keep the cushions down?

Huma Rojo’s dressing room is all about transience, too. A workplace; wig stand, pro lighting, serious ironing board. Hundreds of photos trying to hold the emotions around a limited rep run in a small auditorium in another city. A litle toy theatre proscenium so much more romantic than the real theatre it’s in.

Bonus frocknote: this film passes the Horwell test – women in it talk to each other wisely about clothes. ‘Nothing like Chanel to make you feel respectable,’ says Agrado, wearing so good a Chanel copy from a restrained Lagerfeld period that it stands in for the character on one of the film’s posters. Ever aware of material injustice, she adds, ‘how could I buy a real Chanel with all the hunger in the world.’ (The unbuttoned pink cardigan over black leather trousers for her soliloquy of authenticity never date.) Sister Rosa has to be the best-dressed semi-nun ever, explaining to the other women she feels Prada suitable for religious sisterhood life. Huma’s made-to-measure grande-dame-wear seems to have been woven from her own henna’ed hair.

Veronica Horwell writes for publications including the Guardian and Dance Gazette.

Leave a Reply