I was always going to schedule Wim Wenders’ Pina for Lockdown Theatre Club. Pina Bausch’s work has been a delight and compulsion throughout my theatregoing lifetime. I’ve seen every piece I can, several of them more than once. When her Tanztheater Wuppertal brought 10 productions to London during the Olympic year, I saw them all. I’ve snatched at review, interview and programme-note opportunities. I’m a Pinaholic and a Bauschhead, and proud of it.

And it turns out I’ve written quite a bit about her work, so have collected some of it here – especially around productions that appear in Pina. First is a feature I wrote when the film was released, speaking to Wenders and some of the dancers.

Dancing into a new dimension: Wim Wenders on Pina

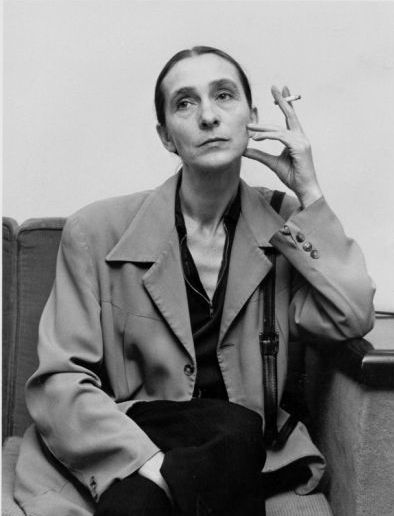

The Tanztheater Wuppertal was performing in Poland in June 2009 when they heard that their director and choreographer Pina Bausch had died, unexpectedly, from cancer at the age of 68. They were devastated. Some had worked with Bausch for years as her troupe from an unregarded German town had become a transforming force in modern dance. “It was a huge shock,” says the limber American dancer Eddie Martinez. “We all expected Pina to live forever.”

The aftermath of the death was terrible. This quiet woman had, through sheer force of will, created a vast body of work that scraped the nerve endings off modern life. Now it was in danger of collapse. “We were in a giant hole,” the Australian dancer Julie Shanahan tells me. What saved them was collaborating on an extraordinary film by Bausch’s fellow German, the director Wim Wenders. Pina captures Bausch’s audacious, wrangling work and celebrates her unique artistry. It preserves the dance, but also makes it anew. It may also be the first artistic masterpiece of 3D cinema.

Several dancers insist that Wenders’ film, far from intruding on their grief, was an essential part of the mourning process. “It was almost a rescue,” Barbara Kaufmann tells me. “Wim gave us the opportunity to pay homage to Pina.” The incisive Spanish dancer Nazareth Panadero agrees: “We were very sad, and not sure what was going to happen. But we felt so close to Wim and the team that we were not alone any more.”

Wenders had met the choreographer when her company performed two of their masterworks, Café Müller and The Rite of Spring, in Venice in 1982. They felt an affinity, he confirms, in part because they were both children of disconsolate, recovering postwar Germany. Panadero also believes Wenders shares qualities with Pina – an observant eye, a reticent sensitivity.

Sitting over a cooling cup of tea in a London hotel, Wenders ruefully admits that he and Bausch had discussed making a film throughout most of their friendship. He simply couldn’t see how to capture her comedy, anguish and visceral extremity. Unlike twinkle-toed ballet, Bausch’s dancers register the full weight of human physicality. “I would have dropped everything immediately, but I always had to admit to her that I didn’t know how to do it. It was almost like a running gag, because she wouldn’t give up and thought that I would eventually come up with the solution.” And, eventually, he did, when he saw 3D film for the first time in 2007.

“I called her immediately,” he recalls. He and Bausch began to plan the film and select the works to be included. “I basically was convinced that 3D and dance were made for each other,” he says. “I wasn’t disappointed – it took a while to get there but the hunch was the right one.”

In other hands, 3D has produced a bombastic display of invention and self-regarding dazzle. Wenders uses the technique with stealth – instead of created hyper-real textures, he relishes the soft layerings of bodies, letting them appear and vanish, draw close or fade away. It’s utterly beguiling, whether we watch a cowed tribe of women endure the Rite of Spring, or see couples in stiff evening wear perform awkward social dances in Kontakthof. You are half observer, half participant – which is precisely the feeling that Bausch’s work often produces. Everyone is implicated in this exhilarating work.

Although the dancers suggest in voiceover something of what Bausch meant to them, there are no discussions of the work in the film; everyone is adamant that would have betrayed their maker, who squirmed when asked to explain her creations. The mere idea makes her longstanding dancer Dominique Mercy laugh: “With Pina it was no help to ask her! She liked to be surprised, she liked misunderstandings when what emerged was incredibly beautiful. I never felt the need to ask things.”

Wenders confirms that Bausch rejected any biographical context. “That was the rule of the game from the beginning; she kept her private life very secret, and rightfully so. Pina herself was not good at words – she was a very funny person in private, but actually never really managed to say much about her art. That’s why it became a film that doesn’t rely on language.”

Bausch’s grave presence nonetheless threads through the film, caught in luminous stills and heart-catching scraps of film. So what was she really like? “Pina was one of the quietest people you could ever imagine,” Shanahan says. “If you didn’t come close to her, you didn’t hear her. That intimacy – that we all learn together as humans – is exactly what her work was about.” So where did this scalding body of work come from? To Julie Ann Stanzak, an American who danced with Bausch for 23 years, her self-effacement masked a ferocious will: “this modest, frail, tender person had a strength that could move a mountain. She could turn water to fire.” Even more simply, Kaufmann believes that “she had questions inside her and they needed to be answered.”

That need burns brightly in her early masterpiece Café Müller (1978), the first Bausch work that Wenders saw. Its impact was decisive. “I couldn’t believe that somebody in 40 minutes was able to tell you more about men and women than the entire history of cinema. It still blows my mind.” Bausch herself appeared as a somnambulist, drifting through a series of grotesque, wrenching encounters. The fractious discord between the sexes – soothed by pure tenderness – is, Wenders believes, “the centre of her work. She created a true anthology of behaviour about the rejection and attraction between men and women. There’s almost nothing left to say.”

Filming these pieces only increased Wenders’ respect for their artistry. Café Müller, for example, was made it a fortnight and its teasing, blundering sequences can feel semi-improvised. Wenders found it to be “incredibly complex and perfect. You see purpose and structure in every second.” Tensions between the original six performers (including Mercy) informed the work – as Wenders argues, “Pina could look into their very souls. Because it is utterly personal, it is also universal.”

Everyone remembers their first encounter with this mighty body of work. Mercy himself felt “an immediate connection” when he took class with Pina and instantly quit the French company he was dancing with: “I packed and left.” For others, the call was almost accidental – Martinez was seeking stardom in New York (“that wasn’t working out so great”) when he auditioned. “I didn’t know who she was, actually,” he admits, and he was unprepared for what he encountered. “I didn’t speak German – I was in shock for the first three years!”

Like other dancers who arrived from cosmopolitan cities, Martinez initially found Wuppertal an incongruous location for a cultural crusade. As he explains, it’s an unremarkable small city in Germany’s industrial belt: “It’s very small, it rains a lot, it’s sometimes too dark.” Wenders films the dancers performing quirky solos in and around the city, taking Bausch’s riffs onto the streets where they were born. Panadero, who planned to stay for a single year admits, “Wuppertal was not so nice for me. But now I like it very much. It is a quiet place, where one can concentrate. It is a city for work.” She has lived there since 1979, and for Bausch, who shrugged off distractions, it was the perfect base. Kaufmann quotes her as saying: “We have nothing to do but work. Let’s go on.”

If Bausch appreciated Wuppertal, it took time for the city to return the compliment. Her work seemed confounding in the early 1970s. Mercy remembers an early triple bill in which he played an eerie invalid in Fritz, a piece about a little boy’s nightmare. “This was not what the audience was used to – people would leave during the performance, slamming the door. Pina got naughty letters, funny phone calls. It was a difficult time.” Even today, reactions can be extreme – Martinez reports spectators stalking out of the disturbing piece Nelken at Salzburg, while a friend watching the company in Edinburgh last summer was harangued by an old woman who denounced them as “decadent.”

The term seems out of kilter with Bausch’s quietly dedicated working method. “She didn’t let many people into the rehearsal room,” Stanzak explains. “She treasured that atmosphere of privacy and intimacy.” Within that cocoon, dancers could explore their most vulnerable and outlandish traits. “She burrowed into the disquiet between human beings,” Stanzak considers. “It’s one woman’s great yearning to understand human need.”

Most dance companies are a nest of lithe but unlined youth. Bausch, however, collected dancers who aged with her. The performers range from twenty to sixty, a unique blend of experience informing the work. “You can grow up and grow old and still consider yourself a dancer,” Shanahan says. “You bring your life story on stage – which is, for me, what most dance lacks.” One of the youngest current dancers, Thusnelda Mercy, truly grew up with Bausch. The daughter of two dancers (Dominique Mercy and Malou Airaudo), she was the first child to be born in the company, and Bausch even suggested her singular name.

The best of Bausch’s pieces emerge like a dream – or nightmare – you’d never known you’d had. Her images are both surreal and steeped in observable reality, drawing on all her dancers had experienced. Stanzak describes a moment that found its way into Viktor, which was based on a residency in Rome. “I saw a woman squeezing spinach, but looking like she wanted to wring her husband’s neck. I brought that into it – I was so moved by this woman at the back of a restaurant at the end of the day.”

The film Wenders and Bausch had discussed was very different to the finished work. It was, he explains, “a film on her gaze, about her look at the world.” As well as four key works (Café Müller, Rite of Spring, Kontakthof and the watery fantasia of Follmond), he planned to shoot her in rehearsal, as well as following her to South America and to Asia. He would also have shown her at home in Wuppertal – “a lot of Pina’s work from the beginning was based on observing people, and I would have shown the city in her eyes.”

Bausch died just days before they were due to shoot some test scenes with the company. “That was the end of the film as I had planned it,” Wenders has said. “We pulled the plug.” It was the dancers who persuaded him not to abandon the project, insisting that he owed it to Bausch. He shot the four key dance works in their entirety, but felt that “that was just the bare bones of a movie. The centre of gravity was missing.”

Instead, he folds extended extracts from the works with quirky solos devised by the dancers themselves in and around Wuppertal. They are heartfelt, quirky sequences often drawn from her work: a hippo lumbers through the river; a woman’s pointe shoes are larded with slabs of meat. They remind you that Bausch built an ensemble of individuals who offered her their own imagination and flaws as raw material. How did Wenders devise these scenes? “It slowly dawned on me that Pina had given us her working method – asking countless questions to the dancers, digging deeper and deeper. So I started to ask the dancers about Pina, and where each felt she saw the best of them, where she recognised them the clearest. These responses became the second part of the film – so it is still a film about her gaze and how the dancers felt she had seen them.”

Bausch had made no plans to relinquish control, so there was understandable uncertainty after her death. Many dancers considered departure and the company might have dissolved, but instead, as Kaufmann says, “Nothing fell apart – everybody came a little closer.” Why?

Martinez, who seriously considered returning to his native America, insists, “I am here because of Pina. She lives in the work, even though she’s not physically here. And I still hear her say, ‘Eddie – feet together.’” Panadero too sees performing as a way of refuting a harsh fact – “It’s one way to make it not seem finished.”

Wenders believes that for Bausch the task of maintaining her repertory of over 40 works was a Sisyphean burden – it is one reason she was keen to find a solution to filming them. Now the artists shoulder the responsibility. Shanahan believes that “the company has come of age. I sometimes think I was in a convent or temple for 23 years – now we go out and give the message.” Their remorseless touring schedule will reach an exhausting peak next summer, when they perform ten works in six weeks in London as a pre-Olympic festival. “Our first wish is to keep alive this repertoire, which is a jewel,” Mercy insists. “At some point we have to go back to a creative process, but it’s so difficult. You don’t replace Pina.” However gruelling, the dancers press on. “On stage there’s this magic,” Shanahan believes. “Our bodies hurt, and our souls hurt, and we don’t know what our future is. As long as we’re doing the works, they survive.”

This is an expanded version of a piece published in the Sunday Times in 2011.

Here are a few extracts from other Bauschiana.

‘It belonged to us’: a tribute to Bausch (Sunday Times 2009)

Indifference wasn’t possible to Pina Bausch’s work – her work inspired either impassioned devotion or revulsion. Bausch, who died this week aged 68, was a choreographer, but much more than that suggests. She didn’t extend the dance repertoire so much as mine ways of being human. Staged on a vaunting scale, her productions always felt personal – it felt like it belonged to us. I remember sitting with the actor Fiona Shaw on a staircase at the London Coliseum as people edged around us, while a rapt Shaw described how Bausch infused the smallest moments with meaning, repeating them until they were transmuted into poetry.

Bausch grew up in the Ruhr Valley, and the industrial town of Wuppertal became her home when she founded her company there in 1973. Generations of dance pilgrims marvelled that such sophisticated work emerged from this uncosmopolitan, even dowdy, place. Just as Fassbinder did in film, she made smalltown Germany the centre of her vision: its tight smile and needling compromises, its barely repressed nightmares.

Bausch devotees craved that scalpel in the psyche. However punishing, Bausch’s pieces were always, urgently, about life. Even when her dancers are merely walking, as Shaw told me, “they don’t just walk – they walk on behalf of humanity.”

How Bausch worked: from a programme note to Viktor (Sadler’s Wells 2018)

Seeing Viktor changed my life. Too much? Maybe, but I’m convinced of it. It was the first Bausch piece I’d seen – the company hadn’t visited London for several years until the redeveloped Sadler’s Wells stage was able to accommodate them. A grim night at the sullen end of winter, and I was full of a horrible cold. Three hours plus of tanztheater seemed a dubious prospect.

I still remember hurtling down the tube escalator afterwards. I couldn’t have felt more alive. Viktor may be much possessed by death, but is often wildly, confoundingly comic. A couple of corpses are married at the beginning of the piece, while a resplendently bored trio of waitresses hobble around their trattoria. In a scene that speaks a surreal truth about ballet, a dancer shoves slices of raw veal into her pointe shoes before teetering off to Tchaikovsky. Bausch and her colleagues recognised that in death there is life – squabbling, desiring, greedy, grieving life, and this hypnotic work runs at it with arms outstretched.

[Viktor was made in Rome.] From the late 1970s, Bausch began the creation of each new work in the same way. She gave the dancers questions or prompts, reading them out in little batches, and building to 100 or more over the course of rehearsal. The dancers would respond in various ways, offering material (some of it very personal) from which the piece would grow. For Viktor, some of the prompts related directly to their Italian visit: What are you looking forward to in Rome? The Romans are working. The Trevi fountain. Something small you saw in Rome today. La dolce vita. Other prompts were less specific to the city: Veal. Vineyards. Somewhere with your breath.

Raimund Hoghe, then the company’s dramaturge, described how the process worked in his rehearsal notes for an earlier piece, Bandoneon (1981). ‘I can feel what I’m looking for,’ Bausch declared, ‘but often I’m unable to say rationally just what it is.’ Instead she urged her dancers to ‘just try it,’ assuring them that there was ‘no need to think in a straight line.’ The records of Viktor show that the artists indeed took some alluring tangents (‘Flirt like a squirrel’) but … Bausch wasn’t merely working with her dancers’ eyes but with their imaginations. ‘I think it’s great that there is a part of you in every piece, a part of your lives,’ she said.

The squirm in your guts: review of Café Müller and The Rite of Spring (Dancing Times)

Café Müller (1978) inhabits a melancholy dream. Its characters seem to be summoned by a sleepwalker in a nightdress (originally created by Bausch herself). As she revolves through the doors, slumps against the wall, everything happens under her sightless gaze… Bausch resists autobiographical parallels, but it seems likely that Café Müller taps into her own childhood, growing up in her parents’ restaurant. Performed by dancers well into middle age, it is particularly poignant, haunted by the sense of a recurring dream, of images that stick unbidden.

If Müller bubbles from an individual’s memory, The Rite of Spring (1975) is a nerve-pummelling masterpiece of collective dread. Bausch’s piece is deeply rooted in twentieth-century trauma. On the peat floor every step sinks into the ground, or raises a spume of soil which gradually speckles the extraordinary dancers; they end up sweaty and stained. Amid the group dances – vast stamping circles, gender-segregated ceremonials – images like a huddle of women in dun-coloured slips inescapably summon the darkest moments of the last century, the camps and chambers. It’s visceral: the squirm in your guts, the nameless terror, the compulsive need to watch.

PLUS

Review of 1980 (a revival which, incredibly, featured some of the original cast, still performing it over 30 years later)

Review of Auf dem Gebirge… (which looks at how history haunts Bausch’s work)

What did it take to work with Pina? I spoke to the dancer Fernando Suels Mendoza (Guardian 2016)

After Kontakthof became the first of Pina’s Tanzabends to make a return visit to New York City, I wrote this blog about it. http://kitbakerii.blogspot.com/2014/11/fear-and-loathing-in-kontakthof.html