It’s long, saggy and full of holes. But there’s more than that to The Night of the Iguana, one of Tennessee Williams’ lesser-loved plays. Though there’s never enough love for Williams’ characters, especially in this play from 1961.

The defrocked priest Shannon has been craving a sojourn on Maxine’s veranda – rum-coco in hand, stretched out in the hammock, which he unfurls as soon as he arrives. In James Macdonald’s cool-eyed revival, Clive Owen’s Shannon (photo above by Brinkhoff/Moegenburg) wears the crumpliest, sweatiest cream linen – a suit for the insouciant gentleman traveller, yet trashed and stained by his unhappy trek through Mexico, ushering a disgruntled party of Texas Baptists. No wonder he squirms in his seamy clothes, can’t wait to unkink his lanky frame and sway unburdened in midair.

As often in Williams, it’s a temporary respite. The world intrudes unsympathetic. The world has a point: Williams wasn’t a judgemental writer – the heart wants what it wants, and so does the horn – but you don’t have to be a snarling Baptist schoolmarm to regret Shannon’s recurring disgrace in pursuit of barely legal women in his care. Shannon eventually cracks up and is restrained in the hammock. There, he’s calmed by another of the hotel’s fretful guests, Hannah (played by Lia Williams with jade-carved poise and a voice like the coolest breeze).

Williams’ stage direction describes it as a canvas hammock, but in Rae Smith’s design it is all rope – knotted, unstable, full of holes, an anchorite’s flail, a nest and a cage. Williams’ characters know how all of those things feel. It also echoes the rope that holds captive the iguana of the title, held to be fattened and tormented. Again, Williams’ characters, striving to surmount despair, know how it is to be prodded by an unfeeling world.

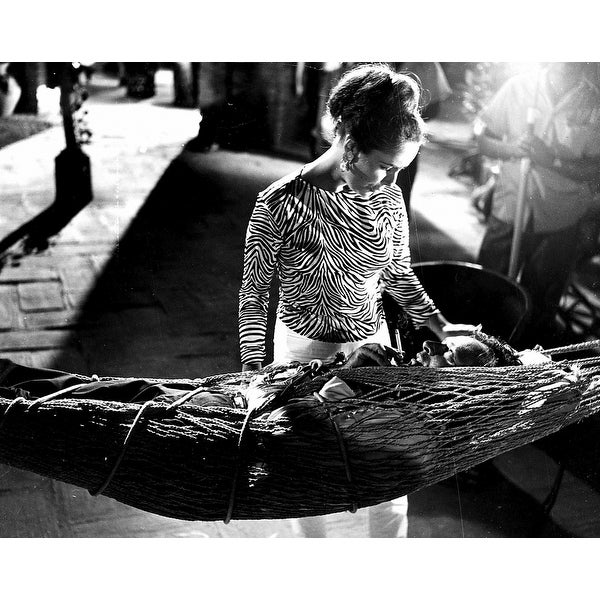

Every element of a theatre production is a choice, down to the simplest prop. The original Broadway production in 1961 was railroaded by its most celebrated actor – Hollywood star Bette Davis, who played Maxine. It’s perhaps no surprise that, though the hammock is associated with Shannon, the image that pops up (via Alamy, above) is of Davis, jauntily ensconced with cigarette held aloft, gleaming triumphantly. She may have tugged the play into something more like The Little Foxes, an expression of her irresistible will.

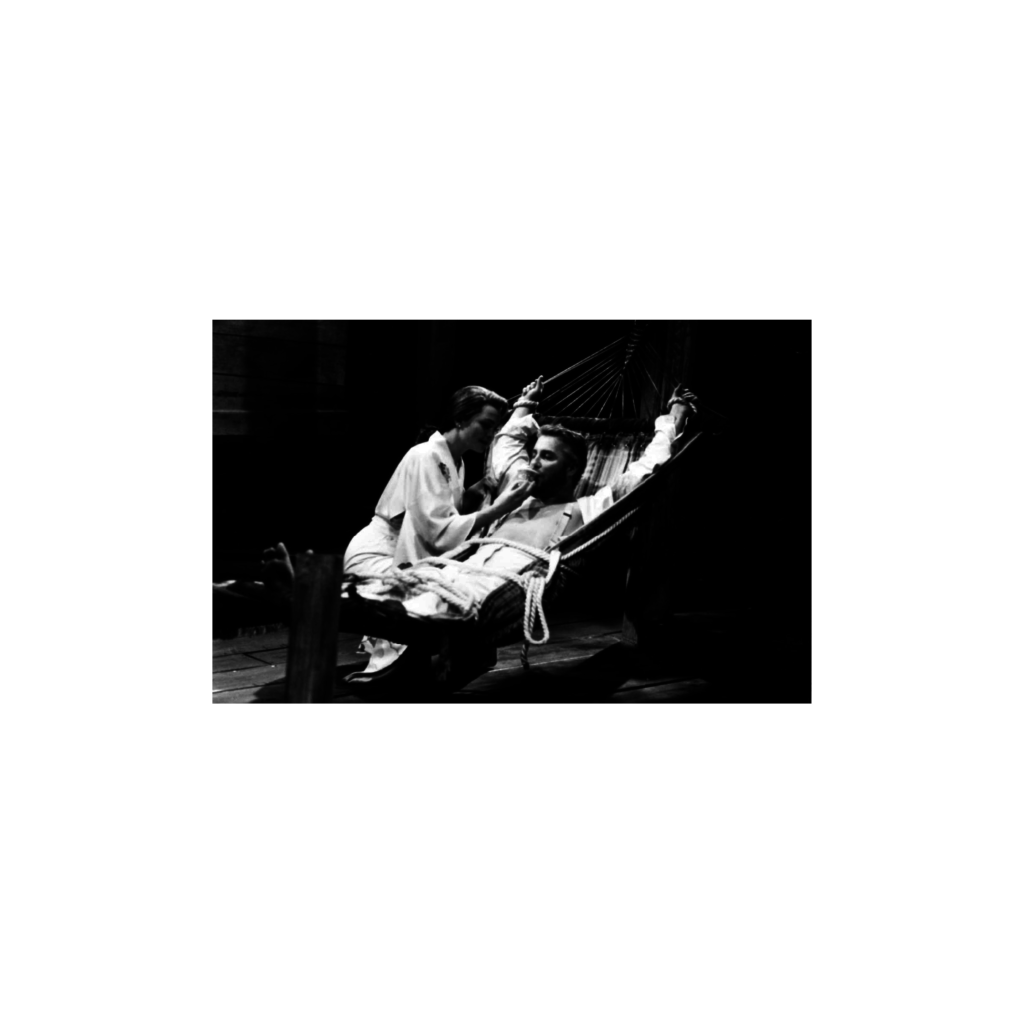

Star power of another kind inflected the 1964 movie. Shannon was played by Richard Burton, whose performances were always shadowed by the anguish of talent never-wholly-fulfilled. He’s not so much restrained in the hammock as straightjacketed, confined like a poetic, madhouse genius (the smiling image above comes from between takes).

Looking at hammockry from other productions makes it clear how the play could skew sensual or spiritual. Even Williams balked at the Christ imagery in his text, but Hannah gazes coolly at Shannon’s self-dramatising pain: a ‘voluptuous kind of crucifixion.’ You sense that in the way Woody Harrelson’s arms are stretched apart in a 2005 London revival.

But relax the arms, open the shirt and a differently voluptuous frisson emerges, as in this Chicago version (1996) where Cherry Jones drips soporific poppy seed tea between William Petersen’s lips.

Hammocks are basic yet fitfully practical: they twist, tip and tangle. Owen always looks properly rocky in his, which is a decent height off the stage. I can’t help feeling that the American Repertory Theater chose a cheat’s hammock in 2017 – blanketed, pillows at top and tail, and barely off the ground. It looks cosy, but should make us feel for those in peril in the air: wandering souls without a nest, hoping for a safe haven.

If anyone wants to stage The Night of the Iguana with actual iguanas, have no fear: lizard-specific props are available. This tiered version would allow the entire play to be hammock-bound.

But if your production was starring the Bette Davis of the iguana world, who wants to give the sense of slumming it without sacrificing her accustomed elegance, then this polished, slatted version might do the job. At last, a hammock that feels like home.

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply