Beauty. Beautiful. Beautifully. It’s just possible I overuse these words. A quick search through my dropbox suggests that in the past year I’ve applied them to: Alina Cojocaru’s acting in Giselle; the final image (watches!) in Robert Icke’s Hamlet; Rebecca Frecknall’s production of Summer and Smoke; the difficult pleasures of Swan Lake; the pacing of The Inheritance; the handbells in A Christmas Carol; Sam Mendes’ precision in The Ferryman; the way puppets can suggest unselfconsciousness. I dread to think how often I’ve used ‘beautiful’ in email (a quick, shaming search suggests that it’s applied to most of the copy and images for Dance Gazette, though in that case it’s 100% accurate) or social media, let alone in burbling conversation.

Here’s the thing, though – to me, beauty isn’t all that. When the British Museum held an exhibition about the body in ancient Greek art called Defining Beauty, I didn’t have a sliver of interest. I’m not beautiful, so how would it speak to me, other than making me drift past chiselled statuary, perving over aloof marble? Stage a show called This Way Ugly, and you’ll have my attention.

Still, my adjectives betray me. I may not have applied them to how people appear – the instances I’ve found seem to describe choices, not faces – but I’m clearly not immune to the idea. Nor are Gob Squad, the Berlin-British performance collective who brought Creation (Pictures For Dorian) to London as part of LIFT. It’s not so much an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, more a deceptively relaxed conversation about art, and how we invest in it as participant or spectator.

Time comes for beauty

As we enter the Purcell Room, Sean Patten is perched on the front of the stage, sketching audience members he finds interesting, while Sarah Thom is arranging flowers at the back. This isn’t mere decoration, she tells us, but the Japanese art of ikebana (‘I did a three-hour workshop’). It’s an art of balance and composition, a process in which beauty builds over time. And time comes for beauty – especially when, as here, Thom trains a camera and a heatlamp on her floral composition, to see what blooms, what fades during the 90-minute show.

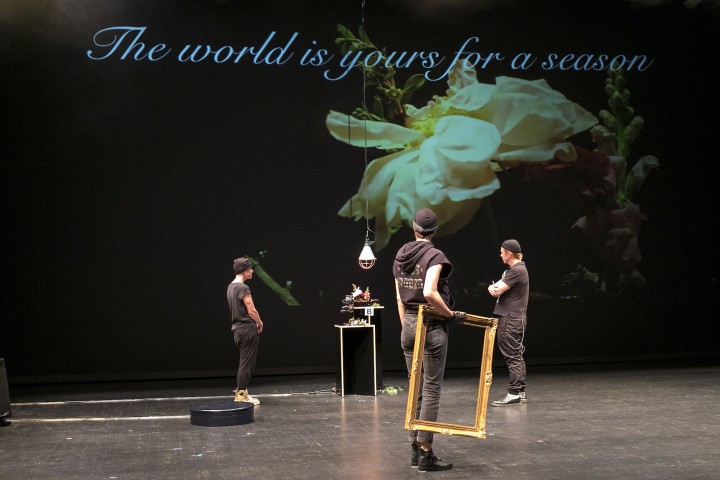

In Wilde’s novel, Dorian’s beauty makes him a work of art – on canvas, but also in life, as he preserves that deathless attraction by a supernatural pact, in which the hidden portrait ages while he remains immaculate. The middle-aged performance warriors of Gob Squad (Thom and Patten are joined by Bastian Trost) also try and arrange life into art, using two trios of volunteers – three student actors aged around 20, three senior performers upwards of 70. They’re all dressed, posed, filmed; asked to speak and then modify their speech. When the Gobbers are (briefly) satisfied they trundle a gilt frame in front of them, give the tableau a title which scrolls in cursive over the screen at the back (photo by David Baltzer, top). But, after a moment, they remake the scenario or propose a new one – beauty isn’t stuck here, but fleet, on the move, wriggling out of reach.

A midlife show, if not a midlife crisis, Creation takes the frets of adulthood – a body that feels older than the mind, a shuttle between feeling wide-eyed and weary, a destabilising mismatch between the person the world sees and the one you feel yourself to be. The company’s warmth ushers you into reflection; it’s a hugely engaging deep dive of a piece. In my own misfit adulthood, I felt protective of the younger trio, enchanted by the older one, involved in the Gobbers themselves (I can’t tell you how much I want Thom to be my friend).

Gob Squad’s show is also a kind of welcoming morality play. For Wilde’s antihero, experience is inimical to beauty. Every act a line, every emotion a wrinkle. Every sin a livid deformation. But the experience of the older volunteers is what makes them shine: their resolve, their reverses, their continuing curiosity. It’s lovely to follow Claudia Boulton’s rackety chronicle of the passing decades, or Stuart Feather’s unquenchable poise. Smiles break out when birdlike Lieve Carchon recreates an off-kilter number from her performing past to close the show. They’re beautiful not despite the lives they’ve lived, but because of them.

Towards the end of the show, we return to the flowers, who have been enduring time’s hot passing. Some buds have wilted on the stem; a brazen bloom refuses to wither; the stick is still a stick. It’s not quite the arrangement it was. It feels more, far more, beautiful.

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply