The best scene in any play in London right now (don’t argue, I’m not listening) opens the second act in John by Annie Baker. Three women – Mertis, who runs a guesthouse in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; her close friend Genevieve; and the much younger Jenny, who is staying at the guesthouse with her boyfriend – discuss the interior life of dolls.

Jenny: When I was little I was always worried about my dolls. I had this one doll, um, Samantha, and I always felt like she was incredibly angry at me.

Genevieve: Of course she was angry. … Angry to be a doll! To be a piece of plastic or glass and to be shaped into human form and trapped! With one expression on your face! Frozen! People manhandling you. And then put in a dress. Put in an itchy little dress!

Jenny: Yeah. Exactly. I felt like she was mad that she was a doll and mad at me for not doing a better job making her life as a doll easier. … I would get up in the middle of the night and lock her in the kitchen cupboard. So I wouldn’t feel her watching me. But then the next morning she’d be even more mad cuz she’d spent all night in the cupboard! And then I’d cry and beg her forgiveness.

Mertis: And would she forgive you?

Jenny: Nope. She never forgave me.

‘It’s capable of anything’

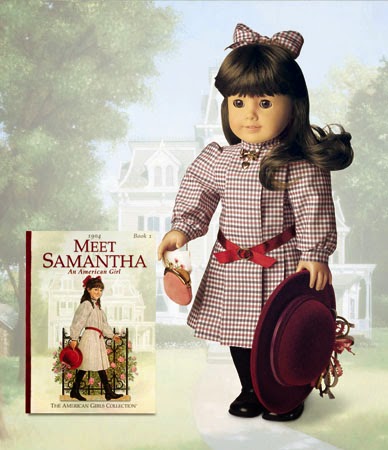

An identical Samantha doll – heritage jewel of the American Girl collection – is on display in the guesthouse, with a host of inanimate colleagues. Mertis begins each scene by trundling open the red stage curtains, and the first time, there’s a giggle-gasp from the audience. The room is decorated to near delirium (designer Chloe Lamford responds with unholy glee to Baker’s stage directions). There are costume dolls and scarlet-capped gnomes with red felt hearts and a chamber orchestra of porcelain angels. There are dolls on the shelves, dolls on the piano, dolls dandling their legs from each tread of the stairs. There are tubby doll babies in sailor suits, a santa on the mini-fridge, even a gnome on top of the grandfather clock.

“Your home away from home,” beams Mertis to her guests, which is pretty terrifying. You can’t imagine how oppressive it would be to live with so much adornment, so many unplayable toys. How would you walk about without knocking things over (Mertis charts a careful route between rooms)? And let’s not even think about the dusting.

Stuffed animals might be odd but endearing, but they can’t even encroach on the national park of weird that is a collection of dolls. What pleasure, what consolation does kindly, uncanny Mertis take from her battalion of voiceless homunculi? What are the dolls doing in this cosy, unsettling house (‘You know it’s haunted,’ Genevieve insists. ‘You know it’s capable of anything’).

Baker often portrays people fumbling their way through a dark fog. The dudes in The Aliens, lounging illicitly behind a coffeeshop; the acting class in Circle, Mirror, Transformation, looking to find themselves through improvisation; the achingly unhappy cinema ushers in The Flick. Young and confused meet older and confused.

Grasping for grace

In John, Baker takes her epigraph from Heinrich von Kleist’s arresting essay, The Puppet Theatre (1810). It reads, in part, ‘grace appears most purely in the human form which either has no consciousness or an infinite consciousness. That is, in the puppet or the god.’ Kleist’s marionettes offer a beautiful image of unselfconsciousness – they can soar into grace because shame or self-awareness cannot distort or hold them back. Humans, on the other hand, can too easily be jolted out of confidence, grasp impossibly for grace.

You see this in the tentative way that Baker’s characters negotiate their lives. Jenny and her boyfriend Elias, skirting around arguments then blundering into them; Mertis ruminating on questions that seem startlingly personal, though delivered with an apologetic hesitance. Only Genevieve, who has endured a lot, has the confidence to pronounce. In the second interval, she steps out from the curtain to tell us her secret – that since going blind on the night of her 57th birthday, she feels as if she is “sitting at the centre of [her] own life with no thoughts at all about what other people are thinking.” It must be a powerful state of being.

Dolls, perhaps, are there already. Especially the look-but-don’t-touch dolls of an adult collector, made for display but not play; they have an incorporate sufficiency, a solidity in their glass and plastic. In a story riddled with unseen characters, especially unreliable men (like Mertis’ sickly husband, Genevieve’s hostile ex and the title character himself), the dolls feel weightily present. They know where they’re going (nowhere). They know what they want (nothing). They don’t care what you think.

Mertis’ dolls wear bonnets and pinafores; they have full-length gowns and a deal of flounce. They aren’t brashly self-aware Barbies or Bratz (their litigious evolution finely skewered by Jill Lepore). Those consumerist stormtroopers are simperingly adult before their time; Mertis’ heritage collection isn’t sexy but forbiddingly grown-up.

And none more so than Samantha, looming over the stage from a door frame, and described by Baker as ‘a terrifying American Girl doll in a doll-sized rocking chair.’ My pal – the unfailingly excellent Veronica Horwell – filled me in on Samantha, a doyenne of the American Girl collection and one of ‘the most popular out of its 70-odd dolls. All the history-based dolls, on which the company’s success was built (it was later taken over by Mattel), came with their own didactic backstories, books, telly specials or moviettes, and Samantha’s was a wealthier life than most.’

This sent me down a doll-stippled wormhole. I learned that Samantha Parkington is an Edwardian orphan (her parents died in a boating accident), being raised in 1904 by her strict grandmother but inspired by her suffragette aunt. I watched a film about Samantha, her blend of propriety and philanthropy (she befriends and educates Nellie O’Malley, a servant girl). I explored her outfits: Samantha wears a dress in checked taffeta ‘in burgundy, brown, and ivory,’ with a hair bow in matching fabric. Underneath (as Elias cruelly reveals), are ‘white cotton bloomer-style underpants with elastic around the legs to make them puffy.’ Her accessories include a heart-shaped locket containing pictures of her dead parents.

She was launched in 1986, ‘archived’ in 2009 but re-released in 2014, because nobody puts Samantha in the corner, let alone in a box in the basement. ‘She was a status object in the late 1990s,’ Veronica wrote. ‘Nice outfits and accessories, and full-scale versions were produced so a girl could be dressed like, pass as, her doll.’ There’s a sentence to make the blood run cold. Samantha doesn’t bend to a child’s needs; instead, you shape your identity around Samantha’s. Although some fans claim her for feminism, Jane Duh on betches.com relates her to the entitled Cher in Clueless, and ranks her as ‘undoubtedly the betchiest of all the American girl dolls’ (there’s some competition, as ‘every American Girl Doll is at least a little bit betchy because they are expensive as fuck and don’t do anything’).

Why does Baker make Samantha the presiding deity of John? She carries a sense of heritage (though not as early as the civil war that shadows Gettysburg), and a prickle of surveillance, looking down from her high perch (‘Do you ever feel watched?’ Mertis asks. Well, yes. Yes, we do). Maybe she’s someone whose choices have been taken from her, or conversely someone serene within them – a moulded icon of American girlhood that mere humans can never attain. She may be an orphan, but isn’t forlorn – rather she seems self-created. It seems telling that Mertis can’t remember acquiring Samantha – rather, it is as if she just arrived, or has always been there.

‘My favourite part is ripping out the hair’

Dolls can provoke as much bracing fury as they do affection. Lepore’s New Yorker article on Barbie inspired Violette Sera Delfina Hiser Skilling,11, to write in recommending ‘doll reconstruction’: ‘erase the features of the doll with nail-polish remover, and then remove the hair and make other body modifications… My favourite part is ripping out the hair, which is very therapeutic.’ There’s a thrilling iconoclasm in this makeover, and you wonder if similar righteous violence lies behind the FAQ on the American Girl website – about what to do if a doll’s hair or neck cord has been cut, her face has been inked, her arms chewed by a dog, or her head pulled off. It’s no accident that the tensest scene in John sees an assault on Samantha. Samantha may have warped Jenny’s childhood, but to see the household god under attack is more than she can bear.

The dolls in John wouldn’t give us the shivers if we, like Genevieve, felt secure in our place at the centre of the universe, serenely unselfconscious. But we’re not, most of us. When Genevieve says goodbye, she does it with wit and grace. When Jenny attempts to respond, she doesn’t get further than ‘I hope we um…’ Even small talk is too huge. What can we learn from the dolls? That assurance may not be ours, not in this lifetime? That grace isn’t ours to hold? Or that we should get out while we can, run before we’re moulded into miserable immobility?

Samantha and her fellow Pennsylvania tchotchkes are just props, just ‘matter’. We probably shouldn’t project a glassy wall of hostility from their sightless gaze. Still, I imagine the last member of the stage crew to leave the theatre each night shivering with unease as they stand alone in the gloom, object of so many frozen, angry eyes.

Production photo of John by Stephen Cumminsky; Samantha sitting top right

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

An absurdly fascinating piece. ‘Nobody puts Samantha in the corner’ Hah!

Thank you, Neil.