Georg Büchner died in 1837 with his masterpiece unfinished – a masterpiece because it’s unfinished, perhaps. The text of Woyzeck is incomplete, the scenes disordered. Based on a real-life murder, it gives naturalism a swerve, and the holes and fractures have lured many subsequent theatre artists. (The one that sticks with me is Robert Wilson’s collaboration with Tom Waits: stylised, scarlet-drenched music theatre.)

Jack Thorne, by his own admission, isn’t a holes kind of writer, and his new version for London’s Old Vic diligently fills in the gaps. Time (May 1981) and place (with the British army in West Berlin) are defined; Frank Woyzeck’s foster-care childhood (bruised by abuse and neglect) and his unhappy army career (including a calamitous tour of Belfast) are detailed. We learn how he met his girlfriend Marie, why they’re together, about her background too. Even colleagues, captain and the captain’s wife bring their backstories to the table.

Thorne also makes the main location ickily present – the ‘meat flat’ above a butcher’s shop that is all that Woyzeck and Marie can afford, raising their baby within the flesh stench. But Tom Scutt – who previously designed a production of Berg’s operatic version teeming with seamy detail – creates a queasily mobile setting. The stage is defined by ranks of panels, descending from above or sliding in from the sides – depending on Neil Austin’s keening lighting, they’re textured like concrete breezeblocks or muffled with padding. They might be forbidding sections of the Berlin Wall; they’re each as anonymous as a brigade drill; they’re grim and grey as the cold war city, an east-west fracture to be policed just as Woyzeck polices his own increasingly untenable fracture.

The slabs start monolithic but don’t hold up. Their surface rends, revealing a flare of blood-red wound, or a sanguine rip of offally tubes and lumps. Visceral is an overused critical adjective, but that’s precisely what we see here.

A history of violence

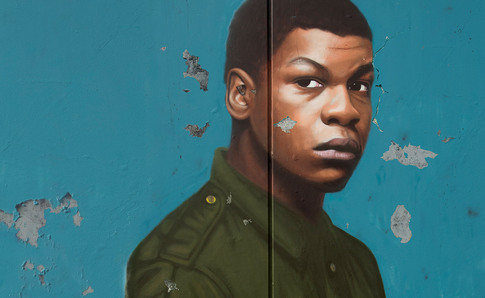

In Joe Murphy’s production, it makes for an expressively un-expressionist reading. And this chimes with Thorne’s desire to foreground what he says ‘is often described as the first working-class tragedy’ – because too much abstraction might aestheticise or distract from a hero pinioned by class. Steffan Rhodri and Nancy Carroll could hardly be more posh as the quixotic captain and his rorty wife – barking their lines and stabbing their superiority like fish knives. Theirs is the voice of assurance – Woyzeck’s, as John Boyega plays him, the wondering tone of someone trying to fit in.

Woyzeck’s mind and body become public property – marshalled by the army, meddled by the doctor, helplessly nurtured by Sarah Green’s Marie. Boyega’s quietly muscled bulk is perfect for the role – he’s a big man and a quiet one, a strong man and a softie. He holds a history of violence that makes him more likely to slam his head into a wall than flare outwards. It’s striking in this production – and in a play which places its hero’s physical and psychic being under such relentless scrutiny – that no one mentions race. It’s up to us to notice that he’s the only non-white character, and to wonder what part, if any, that plays in his distress. It also means the final scene, of harm and self-harm, may play out with unspoken echoes of Othello – another warrior hero whose virtues are warped by the world and turned against themselves.

It’s a rare silence in a version that fills silences, that makes the fragments fit. Incompletion makes Büchner’s play seem arrestingly current; filling the gaps as Thorne does describes a palpable progress into torment.

Follow David on Twitter – @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply