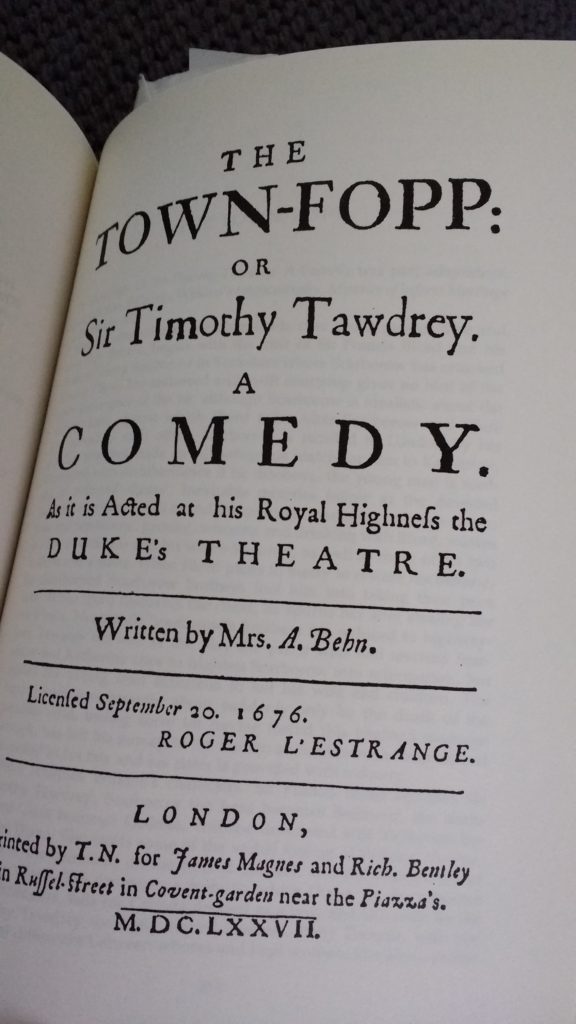

‘Art is our chief means of breaking bread with the dead.’ WH Auden speaks true – one of the pleasures of this little project has been sitting down with the past. Sometimes, however, it’s like sharing a meal, some dishes of which taste familiar, while others are so completely baffling you don’t know whether they’re a starter, a pudding or a peculiar kind of medicine. Such is The Town Fop, a 1676 comedy by Aphra Behn.

Behn’s plays are more studied than staged, although The Rover is currently being performed by the RSC. It’s a pity, because she has a romantic’s heart and an unshakably realist’s head. Realism mostly wins, which is the appeal of her work. Take The Town Fop.

It’s a play of unwilling marriages, messy romances and poor male behaviour. Behn writes well about blokes: their selfishness, silliness, horniness. How life gives them the breaks and lets them break the rules. She enjoys them even as she takes the piss. Her hero, Bellmour, disappointed in love, gets a terrific bleary-hours scene in a Covent Garden den. He has walked out on his unwanted bride on their wedding night, and now desperately tries breaking bad: gambling (he loses), drinking (can’t handle it), casual sexing (heart’s not in it). All he can do is pick fights with his brother and best mate, and fail explain why he’s behaving so weirdly. It’s oddly more endearing than when he’s just a politely devoted lover.

The fop of the title is Sir Timothy Tawdry. Actors tend to play fops as effeminate, affected clothes-ponies, but that’s not Tawdry’s way. He’s rampantly straight, though immensely resistible; he’s too cheap to bother about clothes. All he wants is to live it up with his cut-price entourage (Sharp and Sham) and get laid, while maintaining a mutually-loathing relationship with the brilliantly named bad-time girl Betty Flauntit. He’s a bit hipster, a bit made in Chelsea, a good deal of a dick.

It’s with the women that you find yourself doing serious decoding. What does Behn really think of these horribly imperfect relationships? You find modern minds marooned in an antiquated sexual code – where women will be married off for someone else’s financial advantage, wooed against their will, serially betrayed while somehow keeping their honour. Even when Bellmour’s beloved Celinda disguises herself as a man and proves handy with a sword, she can’t go on the rampage like the blokes do. It’s a caged existence. It feels exhausting.

Behn tugs all the plotlines to some kind of resolution, though you may not be convinced that these compromised unions represent much of a happy ending. Especially Bellmour’s young sister, fresh from a Flanders convent, who is caught up in Tawdry’s half-assed scheming. If the plot is handing out divorces, you’d think she deserves one too, but no such luck. She’s saddled to Tawdry, who as the curtain falls is telling Betty Flauntit, ‘go home and expect me, thoul’t have me all to thyself within this day or two.’ Happy ever after? Fop off.

Sample stage direction ‘Enter Celinda like a boy.’

Sample quote Tawdry: ‘I’m a little mawkish with sitting up all night and want a small refreshment this morning. Did we not send for whores?’

12 Plays of Xmas

I have, surprise, a lot of books. And I have, surprise, not read them all. So, 12 unfamiliar plays, 12 posts: welcome to 12 Plays of Xmas. See previous posts in the series (from Euripides to Lynn Nottage) here.

Follow David on Twitter @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply