For most of these 12 Plays of Xmas, I can imagine how they might be staged, what tone the cast and production team might hope to achieve. But Alkestis… Alkestis is just weird.

Euripides’ wrigglesome play was, according to translator Anne Carson, programmed after three tragedies in the Athenian festival of 438BC. ‘It is not a satyr play,’ she says, ‘but neither is it clearly a tragedy or a comedy. Definitions blur.’

Carson’s classical translations (her Antigone for Ivo van Hove, her fragments of Sappho) are a great meld of voices. As a poet who writes aslant, bone-dry, she links smartly with Euripides, even as she distrusts him. ‘I have had for some years on my computer a file called “Unpleasantness of Euripides,”’ she says, ‘in which I place at random thoughts on this subject, in hopes that the file will someday add up to an answer to the question, Why is Euripides so unpleasant?’

Alkestis isn’t the play to answer the question. Compared to other of the playwright’s works in which spiteful gods toy with human hopes, in which people are exiled, abused, humiliated without pity, this play has a sort-of happy ending. Admetos, one of the Argonauts, is due to die, but the Fates agree to let someone take his place. His parents refuse; his wife, Alkestis, volunteers.

However you cut it, this isn’t a heroic look for Admetos. Before, during and especially after his wife’s death, he is fuming with self-pity. The chorus – who in the grand tradition of choruses, isn’t especially tactful (‘Your pain I understand/ But it is to no avail’) – eventually breaks, interrupting his wail about ‘the empty desert of my bed’ by snapping ‘but you saved you.’

Heroism, of a kind, arrives in the shape of Admetos’ pal Herakles, who blunders into the house of mourning en route to another of his labours. He marches off to reclaim Alkestis from death, but presents her to Admetos as an anonymous veiled woman; he claims to have won her at an athletic event (‘She isn’t stolen, I got her by fighting’).

The end of the play might remind you of The Winter’s Tale: a husband’s mysterious reconciliation with his apparently dead wife. Shakespeare’s Hermione notably doesn’t address Leontes (given that he publicly accused her of adultery, unjustly condemned her for treason and left their baby for dead, it’s hard to know how that conversation might begin). Alkestis doesn’t have quite as much reason for marital froideur, but it’s perhaps just as well that she’s forbidden to speak for three days, until ‘purified of death.’

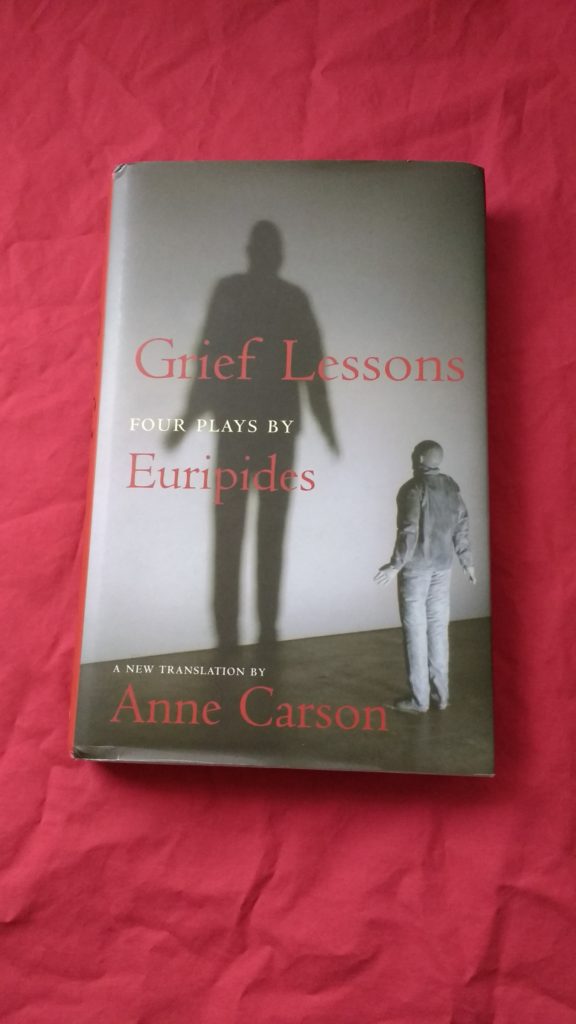

A snivelling widower; an oafish rescuer; a heroine deprived of a sign-off speech. Like I said, a weird play. Set in the palace doorway, it is transfixed between petty comedy and void-staring immensity. How might you pitch it in performance? Carson, whose translation was published in Grief Lessons (2006), compares it to Hitchcock. Her text was performed in New York as Supernatural Wife by Annie-B Parson’s Big Dance Theater in 2011. I’d have loved to have seen the tonal choices they made, line by line, moment by moment. It would surely have been quite a ride.

Sample stage direction ‘Enter Herakles with veiled woman.’

Sample quote Admetos: ‘IO! MOI! MOI! [cry]’

12 Plays of Xmas

I have, surprise, a lot of books. And I have, surprise, not read them all. So, 12 unfamiliar plays, 12 posts: welcome to 12 Plays of Xmas.

Owners by Caryl Churchill

Birth by TW Robertson

Ruined by Lynn Nottage

The Roaring Girl by Middleton & Dekker

Follow David on Twitter @mrdavidjays

Hi David,

Thanks for mentioning Big Dance Theater’s production of Alkestis.

You incorrectly name it Suspended Wife–it is actually called Supernatural Wife.

More details on the production are here: http://www.bigdancetheater.org/shows/supernatural-wife-2010/

Very best,

Aaron Mattocks

Executive Director

Big Dance Theater

Aaron, thanks so much for picking up my error – now corrected. And the production sounds terrific.

Thanks David! It was fantastic. If you’re ever interested in watching the entire production on video, please contact me!