It’s pantomime season, which is as good a time as any to pay tribute to the fine British traditions of smutty humour, sexual confusion, homosexual panic and coming over a bit funny when you think about women’s legs.

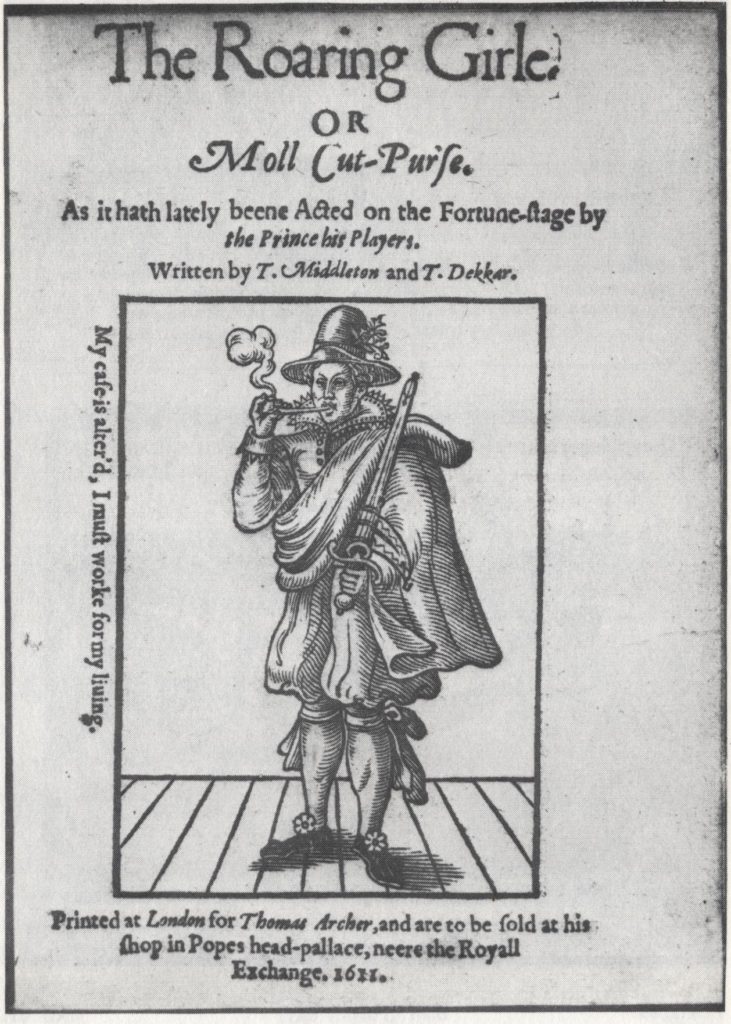

All of the above get a good working over in The Roaring Girl (1611), a Jacobean city comedy in which Thomases Middleton and Dekker fit a real-life gender renegade into a giddy mesh of plots about marriage, lads and adultery. Mary Frith scandalised London by swaggering about in men’s clothes. Moll Cutpurse, her fictionalised version, spends much of the play protesting that she’s not actually a moll, or prostitute, and not actually a cutpurse.

Is it funny? Debatable, at least on paper. But like so many of these 12 Plays of Xmas, its flaws are fascinating. Moll is a good-natured Robin Hood, righting wrongs and enforcing a kind of poetic justice. She remains determinedly free from sexual or romantic entanglement – yet the play’s male characters are fixated on her sexuality – identity, presumed proclivities, general up-for-it-ness. They see a woman in breeches and assume any transgression of gender norms only makes her more available. They hear her protest against marriage and imagine a no-strings romp. Moll may have hoped her wardrobe would take her out of the sexual arena – for the play’s one-track willies, it’s an open invitation.

Luckily, Moll is handy with both the sword and banter, so they don’t stand a chance. Her liveliest moments come towards the end of the play, when she demonstrates her knowledge of criminal slanging, canting with the best (‘What are you? A wildrogue, an angler, or a ruffler?’). It is a scene, blessedly, that gives a brief release from pelvic patter.

The mucky-pup obsession runs throughout the play, much of which is written in the key of fnaar. They demonstrate that, to the English, everything is an innuendo. The dialogue makes naughty with a whole range of vocabularies – from cooking to combat, and a strong emphasis on fashion (so, nudge-nudge jokes about needles and ruffs and, oh, you name it). Many of the yuks are now beyond obscure – my scholarly edition devotes acres of footnote to explaining them, but might as well just say ‘filth’ and leave it at that.

Moll may have to pick her way through the play’s groinal conversations – but she is nonetheless a character we don’t see often in British drama. Delightedly trans, refusing to be defined in relation to men, unashamed and unpunished. It makes an unexpectedly cheering addition to the drama of Brits being weird about sex. This winter I saw a revival of Terry Johnson’s grim Dead Funny – written nearly 400 years later, yet also about remorseless innuendo, miserable marriage and adultery, homosexual panic. The bitterly despondent heroine is only defined as an unhappy wife and wannabe mother. Perhaps she should pick up a sword, slip into trousers and learn the rogues’ cant.

Sample stage direction Enter Moll (in men’s clothes)

Sample quote Sebastian: ‘Methinks a woman’s lip tastes well in a doublet.’

12 Plays of Xmas

I have, surprise, a lot of books. And I have, surprise, not read them all. So, 12 unfamiliar plays, 12 posts: welcome to 12 Plays of Xmas.

Owners by Caryl Churchill

Birth by TW Robertson

Ruined by Lynn Nottage

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply