When the great Victorian actor Ellen Terry was preparing to play Ophelia, she visited a London asylum to observe young women who might unlock the character. However, the madwomen were, she wrote, useless for research: ‘too theatrical.’

The interplay between playhouse and madhouse is a theme running unobtrusively through much of Bedlam, a fascinating exhibition at the invaluable Wellcome Collection, on the history of British asylums through London’s notorious Bethlem Royal Hospital, which in various incarnations during the past 350 years has moved from confinement to therapy, from display to sanctuary.

The exhibition also reminds you of theatre’s lost centrality to British culture. Writers, professionals, inmates could all conceive of themselves in theatrical terms, because theatre was a readily available metaphor for everything. Madness cavorted happily onto the stage during the 17th century, when it seemed less a medical condition than a state of moral or passionate imbalance. Original playtexts by Ford (The Lover’s Melancholy) and Dekker (The Honest Whore), are juxtaposed with a modern poster for The Changeling showing a bifurcated heroine. Lover might shade into lunatic; the jittering madhouse was a barely distorted reflection of the claustrophobic Jacobean court.

A permanent stage

The Restoration’s Bedlam built in Moorfields looked as handsomely baroque as the new theatres in Drury Lane and Haymarket. A poem marking its opening in 1676 compared it favourably to the pyramids and praised its ascent from the ‘funeral ashes’ of London’s Great Fire. Set in genteel grounds, its paths lined with sedately uniform trees, the building slotted into the capital’s new culture of leisure, where the rapidly expanding city was a permanent stage. Inmates were confined rather than cured, and their distress was put on display for a paying audience. Hogarth’s rake ends in the madhouse, where fashionable ladies pass smilingly through the unhappy inhabitants.

Bedlam’s elegant exterior contained chaos – and as maintenance was neglected, the institution’s façade came to figure its misery. An engraving from 1812 shows crumbling brickwork, overgrown vegetation, while unseen inmates dandle a sheet or crucifix from the windows. Three years later, a House of Commons report exposed an abusive regime, including one inmate, James Norris, who for 10 years was chained to a wall by his neck: ‘more from feelings of revenge than for purposes of medical cure.’

This report, which prompted a move to a new building in Southwark, marked a shift in fictional depictions of insanity – from the public behaviours of the theatre to the interior spaces of the novel. Charlotte Brontë, Dickins and Wilkie Collins all described institutions inadequate to the needs of the vulnerable (young, poor, insane). But theatre was still current in the way people thought of themselves. The exhibition includes an incredible series of petitions stitched like samplers in a Wakefield asylum by Mary Frances Heaton. The lucid needlework – underlinings done in neat red thread – describes tangled conspiracy theories, and foregrounds her early exposure to Racine. His tragedy Esther, she argues, has a ‘curious resemblance’ to several ‘remarkable events of my life.’

Drama might form part of a therapeutic regime – an 1843 poster from the Crichton Royal institution announces that the farce Monsieur Tonson by WT Moncrieff will be performed ‘by the Corpus Dramatique of the above Establishment!!!!’ But if earlier playwrights had drawn on the distracted for dramatic effect, their characters formed a frame for thinking about the insane. Sweetly distracted Ophelia provided a model for maddened Victorian femininity: one doctor wrote ‘every mental physician of moderately extensive experience must have seen many Ophelias.’ Hugh Welch Diamond, a superintendent at the Surrey County Asylum in the 1850s, was also a photographic pioneer who used his patients as subjects. One inmate (pictured above) is styled as Ophelia – wrapped in a picturesque shawl, her hair garlanded with leaves. Ellen Terry might have found her too theatrical – or, at least, too conventionally theatrical.

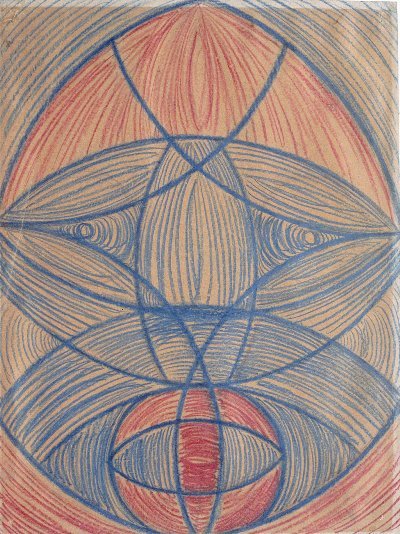

The exhibition includes arrange of works produced by patients – portraits by Richard Dadd and Van Gogh that turn their gaze on their doctors, or an elegant proposal for the Southwark Bedlam by an inmate in the hospital. A century on, there is one of Nijinsky’s paintings (above) – the unmatched dancer creating an anguished face, swirled in blue and red pastels.

If the Wellcome exhibition is any guide, performance as mask or mirror no longer seems a helpful model to today’s mad doctors. Theatre as metaphor may have lost its cultural currency. Those of us for whom distress feels like being miscast in a role, shoved into a play we don’t quite comprehend without a script, or stumbling before the public without a safety net, may disagree.

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply