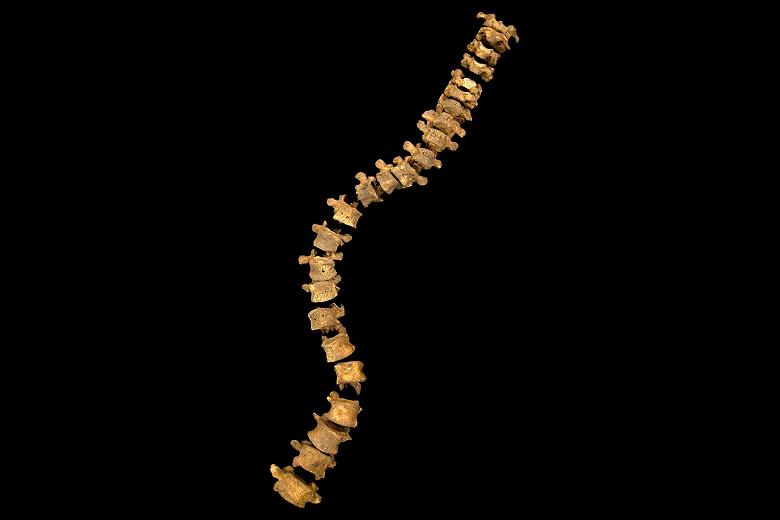

When archaeologists excavating a Leicestershire car park in 2013 uncovered a battle-scarred skeleton, the emergence of its severely curved spine was the first strong indication that these were the remains of Richard III: England’s most notorious monarch, Shakespeare’s irredeemable villain. Further research and DNA testing supported the archaeologists’ theory: hitting a nerve at the juncture of history and myth.

The spine spirals like half the twist of the DNA double helix – Richard III’s identity is half anatomy, half imagination. Rupert Goold’s production of Shakespeare’s history play at the Almeida Theatre begins with that present-day dig, and a protective-suited boffin holds up the spine in a wondering spotlight before Ralph Fiennes steps forward to put flesh on those bones: ‘Now is the winter of our discontent/ Made glorious summer…’

Goold and his designer Hildegard Bechtler don’t dress the play in medieval clobber. The costumes are recent, while the throne, skulls, chainmail curtain aren’t specific to Plantagenet Britain. And yet the prologue drawn from recent headlines, the archaeological-pit-cum-open-grave that remains centre stage, insist that this Richard III is serving up a kind of realness. The ‘authenticity’ of the spine reinforces the authenticity of the behaviour we observe: the politics of masculine ambition, coercion and domination.

Anatomy isn’t identity

What did the Leicester skeleton reveal about Richard? That he did not have a hunchback or a withered arm (Fiennes pulls off his glove to reveal a pitted, leprous-white paw), but a severely curved spine. Mike Pitts in Digging for Richard III reports the researchers’ belief that he developed adolescent-onset scoliosis (rare in males) in early adolescence. The twisted ribcage may have squeezed his lungs, and his height would probably have been reduced to below five feet.

Anatomy isn’t identity, but it might give more credence to the words of Richard’s near contemporaries. Pitts quotes the Tudor historian Polydore Vergil’s description of the king’s ‘short and sour countenance, which seemed to savour of mischief,’ his habit of chewing his lower lip ‘as if the savage nature in that tiny body was raging against itself.’

For Shakespeare, Richard’s deformity indicates a warp of body and mind alike. Different productions play it up or down. Antony Sher’s roiling, bunched shoulders, looming above spindled legs on crutches. Ian McKellen’s Mosleyite rigidity. Mark Rylance’s simpleton-turned-Stalin (Richard as Keyser Söze). Hans Kesting’s blotched face and staggering gate for Toneelgroep’s Kings of War. Fiennes and Goold, however, pin their Richard’s disability to historical fact – this villain isn’t a horrorshow nightmare but an observable political reality.

Fiennes uses it brilliantly to disconcert, rapidly swivelling up and under to peer at a nervous interlocutor. A mere turn of the shoulders can invade a rival’s personal space, allowing him to cultivate a disconcerting sense of movement within stillness. Feet planted on the ground, his glare can arrive at speed and alarmingly close (Fiennes’ eyes freeze over whenever he hears something he doesn’t like – teasing from the young princes, Buckingham’s unwary adjective ‘effeminate’). The condition isn’t exploited for gothick yuks, but as he kneels at his coronation we register the knobbled curl of bones through his tight black top.

Reality bites

Is this the spine of the story, the key to the character? Fiennes, whose strongest midlife performances (Grand Budapest Hotel, A Bigger Splash) have shown him letting rip, is here seethingly contained; his focus is on emotional rather than physical trauma. This Richard is uncaring, but also uncared for. The scenes with his mother, often sidelined, are prominent in Susan Engel’s patrician bewildered towards her own son. Richard’s problems with women are his problems with a world that can’t love him, that he can’t love but can only subdue. In a large cast, the female characters are the most interesting because they see through him, talk truth to tyranny. The men are too invested in the game: vainglorious Hastings (James Garnon), scrolling through his email and missing a gathering coup; canny Buckingham (Finbar Lynch), who finds that even treading carefully won’t wash with a boss who doesn’t care.

Some commentators recoil from the production’s notes of sexual violence – this Richard clamps a hand between Anne’s legs as he proposes marriage, rapes Elizabeth while demanding that she persuade her daughter to become his second wife. These are horrible scenes, but embedded in the language of disgust and conquest. These women’s only power is that they won’t pretend to Richard, and so he humiliates them as viciously as possible. The only woman he doesn’t assault is Margaret, relic of the old regime; he can let her pass because she’s powerless. Vanessa Redgrave plays her transfixingly – ineffably quiet, her incongruous boilersuit marginalising her further among figures in business-like black.

Sher’s book Year of the King reports angsty rehearsal-room discussions about whether a disabled king could lead his troops in battle. However, the Leicester skeleton, with signs of trauma to the head, suggests that Richard was definitely, if defeatedly, in the thick of the action. Goold wisely forgoes sound-and-fury fight scenes for psychic payback around the gaping grave. Fiennes falls back in history: a warning of what happens when reality bites.

Photo above by University of Leicester

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

Fiennes indefinable talent to get inside a character has me very excited to experience the play