There are productions I’ve never seen that are burned onto my brain. As a teenage Shakespeare geek, I devoured books on stage history, describing landmark productions staged long before I was born. I read reviews and memoirs, saw the same few photos. Sally Beauman’s heartfelt history of the RSC was my bedtime reading (still is, sometimes).

Last month John Wyver curated a season of films of RSC productions at London’s Barbican. Some were fairly recent (David Tennant’s Hamlet), but others were vintage stagings I feel I know intimately but had never seen. I caught Vanessa Redgrave’s Rosalind in As You Like It (staged 1961, broadcast 1963) and the first two parts of the War of the Roses trilogy directed by Peter Hall (staged 1963, broadcast 1965).

Both had been filmed for BBC television, and appeared in spanking new black and white prints. In a predominantly greybeard audience (‘Oh to see 50 again,’ sighed the gent behind me. ‘Or 70…’), some people had clearly been there first time round. I wonder how the films rubbed up against memories.

For a first-timer, they were absorbing, and showed the young RSC defining itself with serious fervour. In starkly emblematic productions, the stage was cleared of naturalistic clutter or shift-scene spectacle (the tv histories added some docile livestock for verisimilitude. Bad call). And you can hear the emergence of straight-arrow verse speaking at Hall’s RSC. Clean, direct, scrubbed of ornament. Rational, analytic, understood and understandable. Like the scenery, the words aren’t painted: lines aren’t decorated, nothing is fudged – this is functional speaking for a modern age.

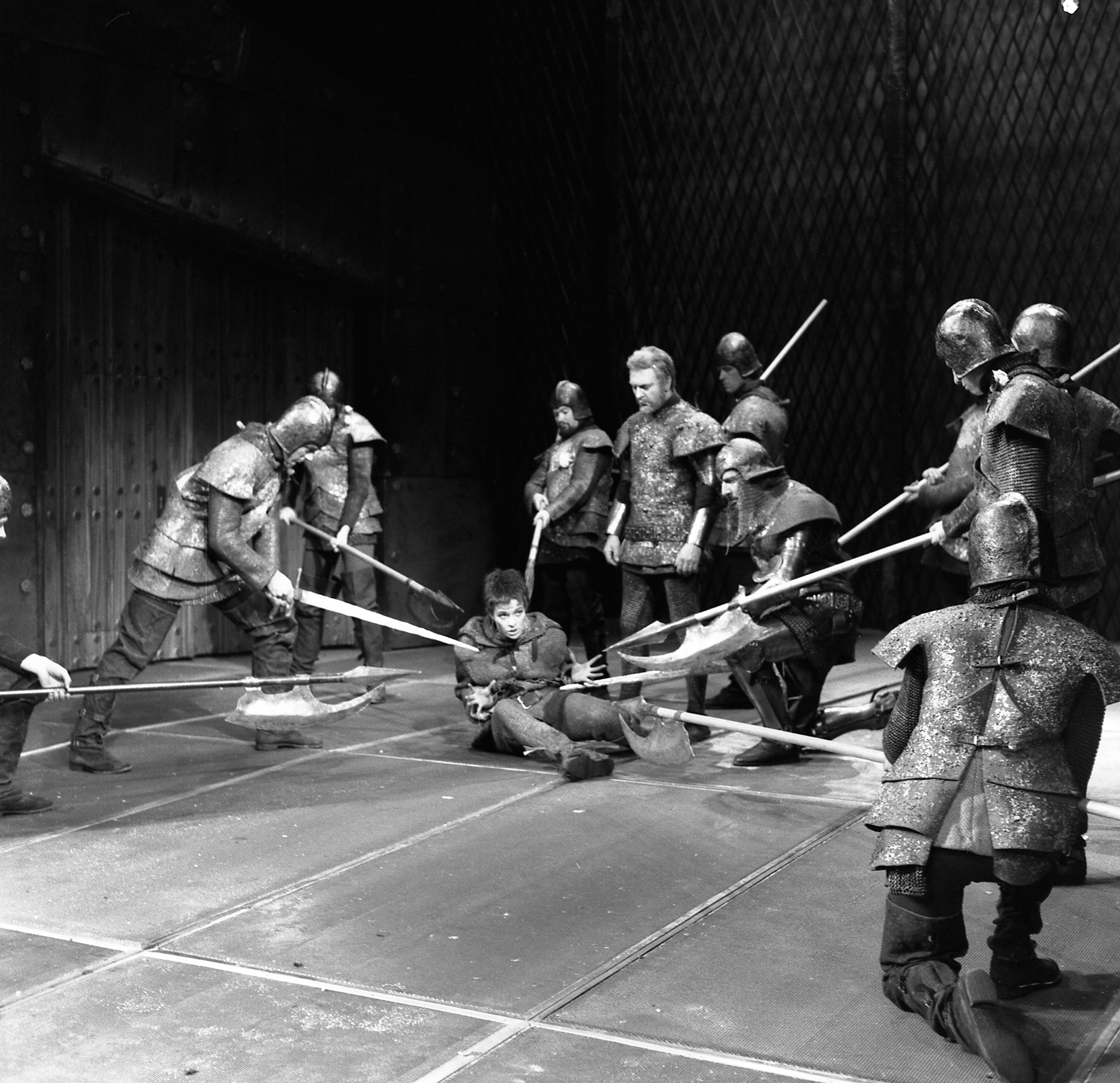

At the height of the cold war, the Wars of the Roses channelled the arctic clang of realpolitick: Hall hoped one ‘blood-soaked century’ would speak to another. John Barton’s text – trimmed from the Henry VI plays and Richard III, but also expanded by his own additions – streamlined the narrative, favouring politbureau switches of allegiance over primal images of loss and myth. John Bury’s design is unyieldingly metallic – inexorable cage-like walls, the central council table, even the costumes. Everything, said Hall, ‘revolved around steel – its texture and its brightness and its capacity to rust.’ In this environment, David Warner’s soft king is the cycle’s prime victim but also, in retrospect, its counter-cultural icon – a peacenik in flowing shirt, boots and unkempt hair.

At crucial moments in the histories, the intelligently mobile camera noses up close to an actor and stays there. It hunkers down when Janet Suzman’s scathing Joan of Arc is at bay. During his ‘molehill’ speech, it pays attention to Warner’s Henry, to whom no one gives much heed. And, most powerfully, it stares unflinchingly at Peggy Ashcroft’s Margaret after she’s tortured and tormented York (Donald Sinden), smeared his face with his young son’s blood. He curses her – the cycle runs on worst-case predictions coming true – and we see her absorb his words, feel yet resist his grief, fear yet resist her fate. Ashcroft’s eyes elsewhere glitter with strategic mischief; her recessed ‘r’ marks a beguiling note of difference among the Anglo earls. But here she absorbs the wider pattern of this cycle, in readiness to become Richard III’s victim and curser-in-chief.

Michael Elliott’s production of As You Like It is less audacious, but reminds us that some relatively edgy tropes began decades ago. In particular, the play begins just as harshly as does Polly Findlay’s excellent current version at the National Theatre, set in a grim corporate world. Orlando’s slogging labour and vicious wrestling bout, the unpromising arrival in a cold-weather arcadia (‘So this is the forest of Arden’): they all shape Elliot’s reading. Redgrave’s Rosalind seems almost cowed, especially against her splendidly crisp cousin Celia (Rosalind Knight). As Arden warms up, so does she – working against the grain of the precise verse speakers around her in a numinous ebb and glow. It was only sad that the film cut Rosalind’s wall-breaking epilogue: why didn’t she buttonhole the camera?

Here’s a production we may never see: Peter Brook’s joyously radical Midsummer Night’s Dream from 1970, an acrobatic white-box dazzler that blazed into the history books. Last year, BBC Radio 4 gathered original cast members (Sara Kestelman, Ben Kingsley, Frances de la Tour and Barry Stanton), plus Brook and his designer Sally Jacobs to discuss the production and its afterlife.

It toured the world and was filmed for Japanese television, but no complete copy exists – Stanton described a ritual burning after just three broadcasts. ‘I’m very happy to think that there isn’t anything,’ Brook insisted. ‘[That is] the way that something must live, through the experience of those who have lived it, and that’s the same for the audience. These are the real recordings of the production.’ More recently, he chuckled, a theatre producer had invited him to revive it in the West End: ‘I sent back a very rude and contemptuous answer.’

Theatrical impact – the particular spark of place and time – can’t be bottled. Even on film, without a genius behind the camera, and a stage director willing to let go, the result will sit between retread and record, deprived of the full pullulating impact. And perhaps that’s as it should be – live performance ebbs away from us, reminding us that we live in time. As Kingsley had it, ‘the ephemeral nature of theatre is a very beautiful and gentle way of introducing us to mortality.’

Main photo: Peggy Ashcroft as Margaret .Photo: R Viner/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

I just read your ‘History Boy’ post from Feb. 2016.. Thank you for validating the power of all those RSC productions from long ago. As theatre students in Boston, my friends and I saw a 1966 pre-Christmas matinee of Harold Pinter’s “The Homecoming” which was having a Broadway tryout at the Colonial Theatre starring Paul Rogers, Vivian Merchant, and Ian Holm among others, in Peter Hall’s flawlessly directed RSC production. We were only 19 years old but the clockwork precision of the acting coupled with John Bury’s stunning off-kilter design set a very high bar. Let’s just say that it compressed everything we imagined the theatre could be into the ultimate master class. However, the bedecked and coiffed Theatre Guild Subscription ladies (all abuzz with holiday chatter prior to act one) never fully recovered from Vivian Merchant’s curtain speech revealing that she had agreed to become the family whore! We loved it.

Donald, what a fantastic memory – now, that’s a production I’d have loved to have seen. And always wonderful to remember that even a revered modern classic began as something provocative and new. Thanks so much for your comment.