It was more than weird to come home on Wednesday night and find MPs voting on British military action in Syria. I had just seen scenes from an earlier conflict, mediated through the giddy solemnity of toy theatre.

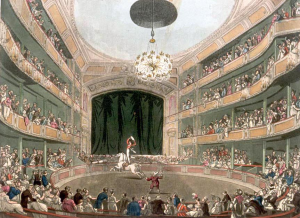

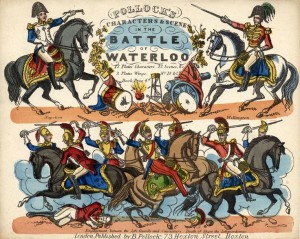

The Battle of Waterloo by JH Amherst, an improbable meeting of reportage and melodrama, was staged in London in 1824. An eye-popper with real horses and highly painted scenery, it was a huge hit for Astley’s Amphitheatre on the south bank (in effect, a proscenium theatre with a circus ring before the stage, allowing for equestrian spectacle). Vast audiences responded eagerly, and the Duke of Wellington himself visited several times. Even when it left the 3D stage, the play remained a staple of the 2D repertoire – versions of the production scaled down for toy theatre were popular for over a century.

The tug between uncomfortable reality and rollicking fantasy must always have been a factor: the play filters the harsh experience of battle through the Georgian melodrama, which darts towards extremes of farce, romance and tragedy. This was the case with the performance by the British Stage in Miniature at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, given added poignancy partly because it coincided with the Syria debate, but also because the cardboard stage sat on a table which had – very probably – displayed Nelson’s coffin on the fallen hero’s return from Trafalgar.

Philip Astley had been a cavalry officer, and in some productions, dragooning horses and military choreography, presented what was in effect breaking news from British campaigns in India. It’s hard to keep hold of reality when the conventions of military melodrama and miniature theatre have such a winning strangeness. The Greenwich performance skewed towards the larky, foregrounding a cowardly Frenchman and the drag role of Molly Malony, an Irish Mother Courage reconfigured as Mrs Brown.

How do you tell a war story? Or celebrate a victory? The productions we pull from contemporary conflict present messy motive, moral confusion and lingering trauma. In Black Watch, Grounded, 5 Soldiers and Lines there are no hurrahs, merely the physical and psychological taint of military involvement.

The Napoleonic wars marked 19th-century Britain – members of Amherst’s original audiences might have known someone involved in the campaign, or mourned their loss. The text’s twist of emotional registers is startling, but not simplistic. In Greenwich, a wind band and vocalists played period music – plangent ballads about separation (‘Over the hills and far away’) that sigh with apprehension. A major plot strand involves a Prussian countess, desperate to rescue her husband from the French, a token of all women left bereft by warfare. And, even when the action was comic, the scenery played it straight – the emotive swirl of fire and smoke as buildings were put to the torch, the wide foreign skies and unsuspecting villages that witnessed the troops assemble.

This may not be our middle east, but it’s a recognisable mood board of military action. Although some strands of plot (including a Scotswoman in male disguise fighting beside her sweetheart) may not exactly be Zero Dark Thirty, others are strikingly level headed. The French are surprisingly undemonised, and Napoleon himself offers calm words and fair play (the actor voicing him apparently caught the tone of Gallic resolve by listening to the wartime speeches of General de Gaulle).

‘Dextrous character manipulation’ meant that strongly gesturing figures slid on and off on wires. ‘Flip tricks’ achieved cardboard marvels. There were coconut shells clicking in the massed horse scenes and butter knives clashing in swordfights. It was, in brief, slightly daft – and a disarmingly grave reminder of how British theatre once put war – its victory and bereavement, its mass combat and individual stories – on the stage. We can now perhaps only achieve this range with paper figures. Real bodies may feel too real.

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

Leave a Reply