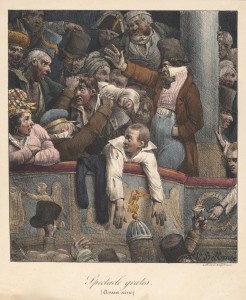

Georgian theatre going was not for the faint hearted. Dandies in the pit, doxies in the boxes, light fingers filching your pockets. If it wasn’t the fire that got you, it was the riots.

I could cope with all that, given enough wig powder and beauty spots. But I’d think twice about the visibility. Until the Victorians contrived to lower the house lights and steep the audience in shadow, spectatorship was a spectator sport. Much of the audience was as visible as the cast, and rather more liable to hog attention. I was reminded of that at Britain’s only working Georgian playhouse – the Theatre Royal in Bury St Edmunds, a cherishable 1819 building which holds actors and audience in curved intimacy. Red benches in the pit, local burghers (21st century edition) in the boxes, a scud of cloud and blue sky painted on the ceiling above. Some Regency theatregoers might have sat on the stage – a knowing chorus, especially in a comedy. This was common practice until Garrick eased them back across the proscenium arch, the better to maintain decorum.

The curve is the thing in this auditorium – light spills from the stage over the audience, and you’re very aware of everyone else, even through the quiet, sad voice of Barney Norris’ exquisite play Eventide, in which three lost souls lose themselves a little more in a village pub garden via a funeral and a wedding. It’s a play made for rapt absorption – and if a prickle of awareness of my neighbours ever tugged me from losing myself, it also completed the circle of introspective melancholy. Look at their lives, look at our own. Feel them.

Shade and lurk

‘Let’s sit and look at the pretty people,’ said my friend the other night, as the press night of The Hairy Ape ended at the Old Vic. Well groomed, well heeled, well connected – an odd crowd, perhaps, for O’Neill’s expressionist drama of alienation, but they made for a nicely tart coda to the fifth avenue swank O’Neill anatomises. Yank, his meaty protagonist, yowls that he can’t find a place to belong in 1920s Amerika. Rubbernecking at the first nighters wouldn’t help anyone feel that they fit in.

Most of my theatre-going is anonymous – I enjoy the shade and lurk. The theatre is a communal space, but also a solitary pleasure, a place to watch without being seen. Each has its core constituency, tweaked on a play-by-play basis (earlier this year, I loved seeing the traditionally staid seniors at the Orange Tree mingle with the young ‘uns at Alistair McDowall’s scorching Pomona – or, ‘that horrible play’ as my neighbour described it on a future visit). You can confirm or skew the profile with every visit, but then subside into your own selfhood as the play begins.

On the other hand, I’ve become a helpless fan of the groundling experience at Shakespeare’s Globe. That theatre rarely does it for me when I sat in the posh seats to review (well, posh-ish. Never has a popular theatre shown so great a commitment to discomfort). Even the best shows can feel too broad, too distant. On your feet and in the yard, however, it’s a different story – even a meh production becomes engaging, playing the trick of intimacy at epic scale. You’re part of the London landscape – from the queue view opposite St Paul’s across the Thames, to the scud of bird, plane and superclouds above. Actors catch your eye – even, if you’re lucky, grab a kiss (Eve Best’s Cleopatra) or take your hand (Charles Edwards’ Richard II). And you’re all in it together, a crowd catching each other’s eye, sharing a grin as Touchstone saunters past, offering a cardigan as someone turns blue in the summer chill. The tension between sinking into a play and being pulled into one has never been so vivid.

Illustration: Spectacle gratis (V&A Museum)

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

“The curve is the thing in this auditorium – light spills from the stage over the audience, and you’re very aware of everyone else.”

Isn’t that why the boxes in (traditionally curved) opera houses had curtains?

That way you could get busy with the doxies in the boxies, or have your supper, or whatever else (especially during the long intervals, while the candles were being replaced) without having all London or Venice or Versailles watching you.

MW, you have thought this through. Also means you don’t have to waste time watching a pesky play…