Benedict Cumberbatch made me cry at Hamlet. Or, more precisely, at the curtain call, with a beautifully feeling, indignant and compassionate appeal for Save the Children’s work in the Syrian refugee crisis. Much of that intelligence and eloquence is in his eagerly awaited prince (the expectancy and rose of the fair state, and then some) – delivered to the most attentive audience in London –but that direct address to heart and head was muted.

As Hamlet takes to cinema screens, I’ve been thinking about director Lyndsey Turner. Shakespeare’s tragedy, like her other recent productions, suggest that she is fascinated by plays occupying moments when the world might change, but doesn’t. A defeated idealist, with each new production she rises to try again.

Turner and designer Es Devlin most vividly captured a turning world in Lucy Kirkwood’s Chimerica, about the search for a protester who defied the tanks in Tiananmen Square. Occupying an ingenious swivelling cube, it rotated between past and present, China and America, each twist adding a layer of complexity. In Caryl Churchill’s A Light Shining in Buckinghamshire, voices from the wilder fringes of the English civil war urge an end to hierarchy and paradise on earth. Again, design carried argument: the stage, an enormous royal table, was gradually cleared and disinterred, soil spilling from under the damask as plebeian speakers were heard. Above, a vast bronzed mirror reflected confident exhortations and their despondent defeat. That the run accompanied Britain’s own general election was entirely apt.

Mired in the past

Turner’s productions operate through assertive design, attentive acting, direction as a conversation with the text. All three traits are in Hamlet, though performances are less pungent than one might hope. Interesting actors too rarely seem interesting: Ciaran Hinds (Claudius), Jim Norton (Polonius), Kobna Holdbrook-Smith (Laertes). This was also somewhat true of A Light Shining: does the scale of her recent work deny Turner time to dig in with her cast? Anastasia Hille has her moments as Hamlet’s mother – but, curiously, Turner gives her final defiant line, warning Hamlet against a poisoned drink, to Leo Bill’s Horatio.

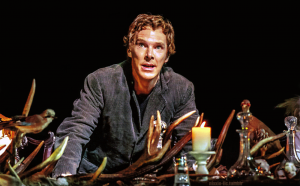

There’s a questing intelligence in Turner’s work, especially when collaborating with Devlin. Together, they suggest that Hamlet’s world is mired in the past. The immensely handsome set looks like an Austro-Hungarian throwback – dark wood and Prussian blue, a grandiose chandelier over the dining table, antlers mounted on the walls. Costumes for the more hopeful characters – Hamlet, Ophelia, Horatio – may edge into the 20th century, but for most of the Danish court it’s always Bismark o’clock.

Cumberbatch’s Hamlet himself retreats to nostalgia (wrapping himself in his dead dad’s jacket) and then to childhood. He opens the evening curled beside a crooning gramophone (Nat King Cole’s ‘Nature Boy’) and later pulls out an immense toy fort, marching around it like a woodentop soldier. The production too becomes a backwards-looking vortex – Ophelia’s wit-wandering babble include not only the usual pathetic snatches of song, but a jumble of lines from earlier in the play. Even as these characters try to move out, they are pulled back.

Even before the official opening, we knew that Turner was making bold textual choices, as a surreptitious review of the very first preview harrumphed that Cumberbatch opened the evening with ‘To be or not to be.’ The soliloquy, like others in the play, is a moveable feast in both early print editions and in production, and using it as an opening proposition for both play and hero seems entirely reasonable. Even though the production rethought this, Turner’s playing text boldly reorders lines and entire scenes to clarify plot points.

Hamlet, often described as a thriller, too rarely feels like one, but Turner achieves a unusually vigorous momentum, with cinematic cut and bleed from scene to scene. The long first half builds unhesitatingly towards crisis, as Hamlet is sent to exile after killing Polonius. As the jaws of the Barbican’s burnished stage curtain close, a flurry of charcoal black debris flurries through the palace – after the interval, we see a rocky slag heap of dark soil and rubble over which the characters pick their way. The old order has crumbled, the murky repressed spills out – but youth isn’t yet confident enough to take over. When stagehands clear space towards the close of the evening, it is only to give Hamlet and Laertes room for their fencing match – and we know how that pans out. ‘Nature Boy’ returns, but a state this rotten needs a more stringent reform programme than ‘the greatest thing you’ll ever learn,/ Is just to love and be loved in return.’

Before becoming a director, Turner worked as a journalist, writing about education for the Guardian (given how she corralls Cumbermania in Hamlet, it’s nice to see that she advocated that teachers use their students’ enthusiasm for Harry Potter as a basis for lessons). Her recent productions all stage moments when the young could inherit the future, but can’t quite achieve it. A new Jerusalem is denied; Hamlet can’t set right his disjointed Denmark; in Tipping the Velvet, her latest show, a lesbian music hall artiste in Victorian England retreats from public transgression to quiet private contentment. The old order is never overthrown, it just engulfs or ignores alternatives. The world could change – but doesn’t.

Follow David on Twitter: @mrdavidjays

I’ve just seen the Hamlet cinema screening – for me too it was the appeal for the Syrian children which made me cry

That’s interesting, Tricia. I’d wondered if the performance would be more emotionally intense on screen.

No. Still intelligent and assured, but too often knew what he was going to say before it was said. Sian Brooke shone though. And your piece above is still spot on.

Oh, nicely put, Richard. Interesting to hear how this came over on screen – and many thanks for the kind words.